Christmas at the Front: A Leicestershire Perspective

24 December 2014

The well-known and illustrated Christmas Truce of 1914 is often considered a unique occurrence within the violence of The Great War. It has been represented in some books and dramatisations as a total cease-fire on Christmas Day, 1914. For many years the only tangible representation of the 1914 truce was a wooden cross, placed in 1999 by the Khaki Chums close to Ploegsteert Wood – or Plugstreet as it was known by the British Tommies. On the 4th December 2014 the Belgian people at Messines unveiled a permanent memorial.

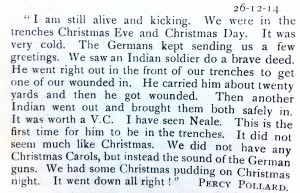

From research into local representation in the Great War, I found a letter in the village of Syston’s Parish Magazine from a Leicestershire soldier, Percy Pollard, dated 26th December 1914.

These few lines reveal that all was not quiet along the entire Western Front at Christmas 1914. The legend that a game of football was played between opposing troops is also a matter of conjecture.[1]

However, Christmas 1914 is not the only recorded suspension of hostilities during the First World War and a second brief cease-fire may have followed in 1915, but is far less renowned, partly because any fraternisation was strongly discouraged by the military authorities on both sides.

The short extract that follows is taken from a paper I presented at an International First World War Conference: ‘Perspectives on the Great War’ at Queen Mary, University of London on 4th August 2014. The paper was prepared using documents that had been deposited at the Leicestershire and Rutland Records office by the relatives of Captain Charles Aubrey Babington Elliott, OBE, JP, of the 8th Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment during the First World War, and Lieutenant-Colonel in the Second.[2] A particularly interesting part of these documents is the correspondence between ‘Cabbie’ Elliott and the German soldier and controversial author, Ernst Jünger.

The paper considers if a possible second Christmas Truce in 1915 was indeed fact or fabrication.

Documentation of such an event only came to wider attention in 1920 with the publication of Ernst Jünger’s In Stahlgewittern, translated into English in 1929 as Storm of Steel.[3]

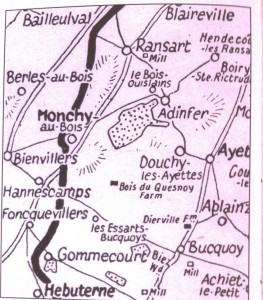

Ernst Jünger was a lieutenant in the 73rd Hanoverian Fusiliers and had been entrenched at Berles-au-Bois, when he took part in an exchange with British soldiers.

Serving with the Leicestershire Regiment in the same area was Captain Charles Elliott who, like Jünger, kept pocket diaries and from these he was able to compare Jünger’s accounts in Storm of Steel with those of his own. On the 19th December 1929, after compiling five pages of notes, Captain Elliott wrote from his home in Oadby, to Ernst Jünger:

‘Dear Mr Jünger,’

‘I have just been reading your Storm of Steel and find that for many months we lived within a few hundred yards of each other. We always heard that you had stopped at Monchy-au-Bois. Was that true?’

Ernst Jünger replied to the letter on the 30th December 1929, from his home in Berlin:

‘Much esteemed Mr Elliott,’

‘Your kind letter gave me great pleasure, for it is curious enough, after such a long time, to receive intimate particulars from a former enemy, whom one scarcely knew, although one lay barely one hundred metres from him. I came only to Monchy at the end of 1915, but I know that at the close of 1914 there was hard fighting round the village.’

Captain Elliott compared his diary with the novel:

‘On referring to the loyal diary I kept, and comparing it with your book, I found many interesting sentences and our stories regarding weather conditions are almost the same.’

He quotes from Storm of Steel, for 30th October 1915:

‘Owing to heavy rain in the night, the trench fell in in many places, and the soil mixing with the rain to a sticky soup turned the trench into an almost impassable swamp. The only comfort was that the English were no better off, for they could be seen busily scooping water out of their trench.’

The weather dominated the writing of both men for quite sometime, speaking of flooded dugouts and a roof dripping like a watering can.

In Storm of Steel Jünger recounts his surprise when on the 12th December he left a shelter he had been staying in:

‘I couldn’t believe the sight that met my eyes. The battlefield that previously had borne the stamp of deathly emptiness upon it was now as animated as a fairground. The throng of khaki-clad figures emerging from the hitherto so apparently deserted English lines seemed as eerie as the appearance of a ghost in daylight.’

He also describes a lively exchange of schnapps, cigarettes and uniform buttons.[4]

The surreal harmony suddenly disintegrated; a shot rang out and a German soldier lay dead. Jünger tells of both sides scurrying back to their trenches whereupon he called out that he wanted to speak with an officer. Several British soldiers went back and later returned with ‘a young man from their firing trench with a somewhat more ornate cap.’ For ease of exchange, they spoke in French. Ernst Jünger castigated the officer for such a deceitful shot. The Officer said it was from the rifle of a soldier in a different Company and not his. When shots hit the ground close to him, the British Officer called out:

‘Il y a des cochons aussi chez vous!’[5]

Jünger wrote that he would have liked to have exchanged souvenirs, but the two men had agreed that war would recommence three minutes after their negotiations ceased. After the talks ended, the German artillery began firing, but once again Jünger was astounded. Stretchers were being carried by the British into the open ground and all firing ceased once more. Jünger wrote that he was very proud of his troops. He said: ‘The Commandant, Colonel Von Oppen, did not approve of our fraternising, but I thought it great fun.’

Jünger’s writing also identifies the British regiment involved in this sportsmanlike exchange. In chapter 5, Trench Warfare, Day-by-Day he wrote:

‘From the British cap-badges seen that day, we were able to tell that the regiment facing ours were the Hindustani Leicestershires.’[6]

Hindoostan was super-scribed on the cap badge in recognition of the Regiment’s commendable conduct whilst serving in India between 1804 and 1823.

As Christmas approached the weather worsened and according to Jünger’s diary for 23rd December 1915:

‘Mud and filth are getting the better of us. This morning at three o’clock an enormous deposit came down at the entrance to my dugout. I had to employ three men, who were barely able to bale the water that poured like a freshet into my dugout. Our trench is drowning, the morass is now up to our navels, it’s desperate. On the right edge of our frontage another corpse has begun to appear, so far just the legs.’[7]

Christmas Eve 1915:

‘We spent Christmas Eve in the line, and, standing in the mud, sang hymns, to which the British responded with machine-gun fire.’ The War Diary suggests it was sniper fire.

On Christmas Day Jünger wrote:

‘We lost one man to a ricochet in the head. Immediately afterwards the British attempted a friendly gesture by hauling a Christmas tree up on their traverse, but our angry troops quickly shot it down again, to which Tommy replied with rifle grenades.[8] It was all in all a less than merry Christmas.’

Whilst there is some discontent with Ernst Jünger’s account, and perhaps what happened in December 1915 cannot be considered an accomplished truce but a series of fraternisations, this account is about a fellowship and has culminated in two opposing officers being able to find a personal truce through the written word.

Karen Ette, August 2014,

This abridged version December 2014.

References:

[1] Chris Baker, The Truce: The Day The War Stopped (Stroud: Amberley, 2014)

[2] Matthew Richardson, Fighting Tigers: Epic Actions of the Royal Leicestershire Regiment (Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2002), p. 85.

[3] Ernst Jünger, Storm of Steel (London: Penguin, 2004)

[4] Jünger, p. 57.

[5] ‘There are some swine on your side too!’ Jünger, Storm of Steel, p. 57.

[6] Jünger, p. 58.

[7] Jünger, p. 58

[8] Jünger, p. 58-59. The War Diary confirms that rifle grenades were fired by the Leicestershire Regiment.

Ian Keil Remembered

18 December 2014

Ian Keil Remembered

by Alison Mott

One summer Saturday 8 or 9 years ago, I visited the Old Rectory Museum in Loughborough’s Rectory Place and chatted with a kindly and very knowledgeable gentleman about local history.

He told me of the slums which had once stood not a stone’s throw away from the Museum, cheek-by-jowl with All Saints’ Parish Church, at one time the most affluent ecclesiastical living in the country. He told me of the ancient artefacts which had been found when those slums were demolished, pots and old shoes and infant skeletons, discovered at the bottom of wells. He was as interested in the human story behind the artefacts as I was and we speculated sadly on the out-dated social conventions which might have caused women to dispose of babies in wells.

I asked where I would find more stories about Loughborough’s past and the gentleman told me about Loughborough Archaeological and Historical Society (LAHS) and its programme of winter talks. I mentioned that I’d like to join and – mindful of the Society’s role in having saved the Old Rectory from demolition – that I’d like to take on an ‘active’ role and, perhaps, join the committee. ‘But I don’t have a History qualification,’ I said.

‘You don’t need to have a History qualification,’ he replied, ‘quite a number of our members don’t. History belongs to everyone, you know.’ He was so friendly and encouraging that I joined both the Society and the Committee not long afterwards, where I was made to feel welcome and useful from the very first meeting, and where my own journey into the world of researching local history began.

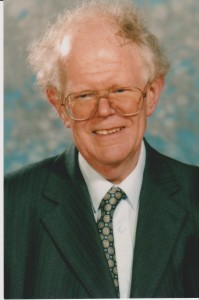

That elderly gentleman, it turned out, was Ian Keil.

For quite some time I had no idea who Ian was. I didn’t know he was a well-respected historian and a specialist in medieval history. I didn’t know that he was, in fact, president of the LAHS, as well as chairman of Loughborough Civic Society, a member of the Town Team [1] and a committee member of the Friends of Charnwood Museum. I wasn’t aware that he had co-created the ‘Exploring Loughborough’ heritage trail, nor that he was co-author of numerous texts on the area’s history, including the ‘Bygone Loughborough in Photographs’ series and the iconic and phenomenally successful ‘Loughborough, Past and Present’ book, published in 1988 by Ladybird and created at Don Wix’s dining table.

As a former history teacher at Garendon High School, Don Wix had been collecting local historical information in notebooks for years. He credits Ian with having prompted him to turn the notes from his hobby into texts for sharing with the public. I understand that others had similar experiences. Ian certainly supported my developing interest in local history and I will forever be thankful for the time, information and advice he and Teresa gave me over the historical pieces I wrote for my Master’s degree. I feel very privileged to have had those pockets of time with them both.

Ian was unwell in 2012 and by summer it seems he knew he was dying. As well as writing the eulogy for his own funeral, he drafted a piece about himself with Teresa. Typical of Ian’s sense of humour, he gave this the working title ‘Becoming History’. Sadly, Ian passed away 0n 17th October 2012, aged 79. In November 2014 Teresa kindly completed the text for inclusion on this website. She also sought permission for us to use a piece Ian wrote about his childhood for his great-nephew, Trystan.

The greater part of Ian’s working life was spent at Loughborough University – joining it as Loughborough College of Technology in 1962 and retiring in 1990. His life, like that of so many others, shows that the history of town and university intertwine in ways which extend far beyond academic endeavour. The University’s history is also that of the men who constructed it, the people who live alongside it, of the men and women who work within it and of the fabric of the town in which it sits.

It makes sound sense, therefore, for the University and the local community to come together to preserve their shared history, and it is the intention of the Loughborough History and Heritage Network to do what it can to enable this to happen.

In doing this, we dedicate the project’s website to the memory of Ian Keil and his passion for recording history, as well as to the principles of inclusion and encouragement which he advocated.

[1] an advisory body to Charnwood Borough Council

[wpdm_package id=900 template=”link-template-default.php”]

[wpdm_package id=899 template=”link-template-default.php”]

- Ian with Ernie Miller, Teresa Keil, Don Wix and Vice Chancellor Shirley Pearce, at the opening of Charnwood Museum’s exhibition of the history of Loughborough University, May 2009.

- Games Activity Day, the Old Rectory Museum, Archaeology Fortnight, July 2009

- Ian Keil and Don Wix processing to Loughborough Parish Church as part of the College Sunday Centenary celebrations, October 2009.

You can find out more about Charnwood Museum’s Centenary Exhibition here and watch a film about the College Sunday Centenary celebrations here.

Agriculture and the contribution of Robert Bakewell

17 December 2014

- A painting of Robert Bakewell on display at Charnwood Museum

- Dishley Grange near Loughborough, home to Robert Bakewell and the site of many of his innovative farming practices

Agriculture and the contribution of Robert Bakewell

I J E Keil BA, PhD and D H C Wix, DipEdTech

From: Charnwood’s Heritage, 1976

This chapter is in two parts: the first outlines the development of agriculture from earliest times until the present, and the second highlights the contribution of Robert Bakewell, one of the great agricultural pioneers. Agriculture dominated the economic and social life of the area included in the Charnwood Borough until the nineteenth century, when other industries and services diversified the economy and reduced its relative importance.

Agriculture began with permanent human settlements in pre-historic times which took advantage of the lie of the land and its inherent qualities.[1] The river valleys and the Wolds were first settled, allowing the cultivation of good soils and access to vital meadow land which provided the hay for over-wintering livestock. Charnwood Forest had much less attractive terrain and most of it remained a hunting area into historical times. Place names suggest that the district had a mixed ethnic settlement pattern, but of its agriculture the first written evidence comes from the Domesday survey of 1086.

Domesday recorded a major redistribution of land ownership which had occurred in the twenty years following the Norman Conquest.[2] The principal agricultural activity was in the river valleys and in the eastern part of the Borough area; Charnwood Forest seemed mainly untouched. Agricultural information suggests an extensive pastoral farming economy. Meadows were highly prized and arable probably sufficed to meet immediate local needs. Sheep rearing earned surpluses to pay rent, to finance improvements and, in the longer term, to support increasing populations.

The subjection of Charnwood Forest to more than haphazard use owed much to the expansion of population and the activities of larger landowners, particularly the newly-founded religious houses of Garendon Abbey (1133), Ulverscroft Priory (twelfth century) and, to a lesser extent, the Knights Templar at Rothley by 1203. Sheep made good use of pastures and, undoubtedly, some arable was associated with new villages such as Garendon, Shelthorpe, Bradgate, Woodhouse and Newtown Linford. Lay landowers such as the Le Despensers shared in the colonisation.

One other change in the landscape attributable to the larger landowners of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries was enclosure for parks which provided reservations for game. Lay and ecclesiastical owners established parks. Garendon Abbey had two: Dishley and Garendon, lay lords created Loughborough, Beaumanor, Quorn and Bradgate. These enclosures symbolised the privileges and pleasures of land owning.[3] The Burleigh park at Loughborough existed by 1530 and in subsequent centuries land was set aside and landscaped for visual amenity as well as game, as, for example, at Prestwold.[4]

Enclosure for agricultural purposes occurred on a limited scale in the Middle Ages; the adverse climate of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, as well as the depredations of disease, extinguished some villages as at Hamilton, Prestwold, Shelthorpe and Dishley, where the ground reverted to pasture. The reduced numbers [of people] favoured peasant farming rather than large-scale estate farms, which utilised rents of labour services and low-wage labour. Thus, by the early sixteenth century the natural advantages of heavy clays for grazing and availability of meadows gave sheep continuing prominence.

Population growth in the early sixteenth century made the market for wool more profitable so that enclosures continued, allowing landowners to free themselves from the restraints of common field farming.[5] The progress of total enclosure, not only for grazing purposes, of entire villages occurred at Dishley before 1529, and by the end of the seventeenth century at Beeby, Buron-on-the-Wolds, Cossington, Cotes, Prestwold, Wanlip, Woodhouse and Woodthorpe, and partial enclosure had taken place at Barkby, Barron-on-Soar, Syston and Thurcaston. Private Acts of Parliament made enclosure easier during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and almost the whole of the rest of the Charnwood area was enclosed by 1829 when the Charnwood Forest and Rothley Plain Act became effective. Small amounts of common land remain at Anstey, Loughborough and Wymeswold. The landscape usually reveals parliamentary enclosures by the geometrical shapes of fields and the straightness of the roads.

Although pastoral farming had pride of place since the Middle Ages, improvements were not confined to livestock and changes in arable farming meant that even in the open field areas the prevalent three fields [system] did not stop new crops or variations of rotation.[6] Major innovations generally awaited enclosures and by the end of the eighteenth century root crops formed an important part of the arable wherever soils favoured their cultivation. Thus in the crop returns of 1801 about one-fifth of the land in Birstall, Cossington, Quorn, Swithland, Syston, Thurscaston and Wanlip produced turnips.[7] Potatoes became a field crop in the county during the eighteenth century although as late as 1801 the acreages were much smaller than for turnips. Beans and peas contributed notably to the farming output of the eastern parts. In 1801 wheat was the largest grain crop with barley second and oats third. Livestock farming improved, the grazings being used to fatten cattle from Scotland and Wales on a larger scale, whilst the milk surpluses from dairy herds increased the output of cheeses, particularly of the Stilton variety, and made feasible extensive pig rearing. The demand for agricultural produce justified investment in drainage, new buildings, fertilisers and tools. However, the prosperity of the middle decades of the nineteenth century ended in the 1870s when poor harvests, animal diseases and imports of cheap produce from overseas combined to reduce profits from farming. Arable acreages declined, and pigs and dairy cattle remained the most advantageous ways of farming.

The First World War brought a modest return of prosperity with increases in arable to meet the national needs for corn. This revival soon ended with the return of peace and farming practices reverted to their pre-1914 character despite the inauguration of marketing boards in the mid-1930s. The Second World War brought radical changes: the trends of over a half a century were reversed. Subsidies encouraged conversions of pasture to arable to supply the nation with corn and potatoes: pig and poultry farming were reduced in size and horses were replaced as a result of mechanisation between 1940 and 1945.[8]

The modern farming industry still exploits its natural advantages, but acreages of arable produce cash crops of potatoes, sugar beet and barley. Grasslands support dairying herds and some of the beef produced. A conspicuous change in the landscape has been the removal of hedgerows in places to make fullest use of machinery, whilst landowners have increased farm sizes during the past two decades. The international economy shapes farming policies with government intervention through pricing and other controls.

I.J.E.K

Robert Bakewell of Dishley

The local work of Robert Bakewell, born in 1725, had national and international influence on methods of raising pedigree livestock.

He farmed at Dishley, just north of Loughborough, at the time when England needed more food for the growing industrial population, and he had travelled widely before he took over Dishley’s 440 acres in 1760. Studies of livestock management and the science of pedigree breeding prompted his own experiments.

Bakewell was of English yeoman stock, a genius whose original thinking changed [farming] methods in the face of scepticism. Many who disliked him later adapted his methods and hired his breeding stock.

In the early 18th century there had been no great demand for extra food. Farms and markets were so isolated by bad roads that new ideas were slow to percolate. Hardly any root crops were grown as fodder and many animals were killed before winter. By the end of the century enclosure was nearly complete and Leicestershire was almost all grazing country. Bakewell was quick to see the advantages of ‘effective control of stockbreeding’ in enclosed fields and with the need for more food his aim became ‘to produce 2 lbs of mutton where there was only one before.’ His breeding principles were to produce ‘beauty of form’, ‘a proportion of parts’, ‘less offal and more meat’, ‘good texture of flesh’ and ‘quality of fattening at an early age’.[9] He always brought together superior branches of the same breed of animal and bred in-and-in to produce his special types.

Before Bakewell’s time, cattle had been used mainly for draught purposes and not so much for food. He used long-horned heifers and a bull from Westmorland to produce the Dishley Longhorn, unrivalled for soundness of form, smallness of bone and aptitude to acquire fat.

His famous bull, Twopenny, lived for 26 years, having serviced many animals at 5 guineas a time. However, soon after Bakewell’s death in 1795 the Longhorn breed were replaced by Shorthorns because of the need for milkers and dairy produce in Leicestershire.

Bakewell’s real claim to fame was the New Leicester Sheep. Wool had for long been England’s source of wealth, but the sheep before 1700 was only a wool provider although it also acted as ‘a four-legged dung-cart’.[10]

The aim at Dishley was to produce a sheep with ‘the greatest weight of mutton, for the least expenditure of food, in the least possible time’. Continental Longwools were subjected to in-and-in breeding to produce the Dishley Breed, later to be called the New Leicesters. These were described as having clean heads, straight, broad, flat backs, round barrel-like bodies and they were inclined to make fat at an early age. Bakewell let his rams to farmers for a whole season instead of selling them, and in 1784 was receiving 100 guineas per ram. However, this new breed proved unsuitable for severe climates as it only grew a light fleece. As with the Longhorn, it became unpopular and gradually disappeared. The last of the breed kept in Leicestershire were at Beaumanor up to 1922.

Dishley was also noted for innovation in farm management. There were usually about 15 acres of wheat, 25 of spring corn and 30 of turnips. The rest, about 330 acres, was nearly all grazing land with 60 horses, 400 sheep and 150 other beasts.

Bakewell used three-year heifers for ploughing. Later he used only two horses instead of the usual six. He levelled the fields, cleared the brook, built sluices and channels and irrigated his fields.

In conclusion, although Robert Bakewell was a pioneer animal breeder he ‘was more apt to act well than to tell clearly how he acted.’[11] We do know that what he tried to do within the limiting influences of his time, came from his attempts to break with tradition and to adapt farming to the changing needs of his countrymen.

D.H.C.W.

[1] PYE, N. (ed.), 1972, Leicester and its region, Leicester: Leicester University Press, has the most recent discussions of soil characteristics and early human settlements. See: THOMASSON, A.J., REEVE, M.J. and HOOPER, A.J., Soils, 114-132; PEEK, R.A.P. and McWHIRR, A.D., Pre-historic and Roman settlement, 195-217; MILLWARD, R., Saxon and Danish Leicestershire, 218-234.

[2] Ibid., MILLWARD, R., Leicestershire 1100-1800, 235-263; also HILTON, R.H., Medieval Agrarian History in The Victoria History of the County of Leicester, 2, 145-198. London: Oxford University Press and THIRSK, J., Agrarian History, 1540-1950, ibid., 2, 199-264.

[3] CANTOR, L.M., 1972. The Medieval Parks of Leicestershire. Trans. Leicestershire Archeol. Hist. Soc. 46, 9-24.

[4] NICHOLS, J., 1795-1815. The History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester. London. For Prestwold see 3:1, 355, and for other halls with parks under the appropriate parish entries.

[5] BERESFORD, M.W., 1949. Glebe Terriers and Open-Field Leicestershire in HOSKINS, W.G. (ed.). Studies in Leicestershire Agrarian History,. Leicester: Leicestershire Archaeological Society.

[6] THIRSK, op. cit., 212.

[7] HOSKINS, W.G., 1949. The Leicestershire Crop Returns of 1801 in HOSKINS op. cit., 127-153.

[8] TURNER, S.E., 1972. Agriculture in PYE, op. cit., 325-339.

[9] COOK, H.W., 1942. Robert Bakewell of Dishley, The pioneer of English stock-breeding. Ms. Leicestershire Libraries and Information Service. Loughborough Library. A.A.1132., 14-26.

[10] Ibid. 28-38.

[11] HOUSMAN, W., 1894. Robert Bakewel. Jl. Roy. Agric. Soc., 5:1.

Research volunteers wanted

10 December 2014

- Volunteers carry out research at Loughborough Library.

The Charnwood Great War Centenary Project is looking for enthusiastic volunteers to help with research on the people named on the memorial plaques at All Saints and Holy Trinity church.

There is no reward apart from the pleasure of reconstructing past lives starting with just a name and maybe a military record.

You could use censuses, genealogy websites, electoral registers, contemporary newspaper reports and photographs.

No costs involved. Experience not needed, training and support available.

Work in a friendly group, with interesting visits organised or on your own.

If interested contact Janet Grant, research coordinator, in the first instance, sending an email with a number we can contact you on to janet.grant@gmail.com

Letters from the Trenches

9 December 2014

For 6 days in November 2014, Loughborough Baptist Church in Baxter Gate held an exhibition and series of lunchtime talks to mark the centenary of the start of the First World War. The exhibition was held in the Assembly Hall which from 1915 onwards was used by Baxter Gate Hospital to accommodate wounded servicemen.

The exhibition centred on a collection of more than 200 papers discovered at the church at the back of a cupboard. Written by servicemen who’d attended the church’s Sunday School in their youth, the papers were letters of thanks for Christmas parcels donated by members of the congregation and sent out to the men between 1916 and 1918. Sixty-five Baxter Gate men received these parcels, with 105 men listed on the Roll of Honour as having served in the war and 23 fatalities named on the memorial in the church forecourt.

A booklet containing extracts of the letters, the names of the men who received them and information on how the scheme was organised has been compiled by the Local Baptist History Group. This is available from the Church Office, as is a CD of the scanned documents themselves.

The office is open every weekday morning and can be contacted on 01509 215642 or by emailing office@lbcweb.org.uk at other times.