Strike at the Brush Works in 1906

31 January 2021

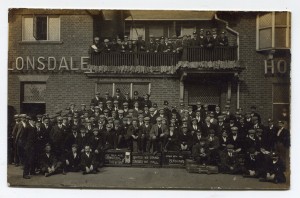

Brush Strikers meet outside the Lonsdale Pub in 1906 Postcard image scanned by collector Heather Copley.

‘All Men are Brethren’

‘For both he that sanctifies and they who are sanctified are all of one: for which cause he is not ashamed to call them brothers.’ Hebrews 2:11-13

In June 2014, the Loughborough Archaeological and Historical Society (LAHS) Committee received a photocopy of an old black and white postcard from Heather Copley, a collector from Leighton Buzzard, with a request for information on the event shown in it.

The image is of a group of men, each with a ticket in their headwear, grouped outside a pub named ‘the Lonsdale Hotel’. The men sit and stand around boxes chalked with the words ‘united we stand, divided we fall’, ‘down with the blacklegs’ and, most intriguingly, ‘all men are brethren’, with an arrow pointing to what appears to be a lump of coal above the caption ‘part of black’. A young man on the right rests a board across his feet with the words ‘sent out of Falcon, victimised’ in cursive writing. A shadowy figure of a pot man can be seen in the right-hand window.

Heather bought the postcard in an album of cards at Tring Market Auctions and though the reverse was un-used and bears no postmark, it is subdivided and printed with the words ‘for Inland Postage’ which, she estimated, placed the event between 1904 and 1909. A number of the other cards in the collection were of Loughborough and this prompted Heather to begin her investigations in the same area.

An internet search confirmed the existence of a Lonsdale Hotel in Loughborough and a quick look at Burder Street on Google Earth Street View showed it to be the same building as that in the photograph. Hence Heather contacting the LAHS.

The LAHS Committee contacted local historian Tony Jarram, who was able to confirm that the picture was related to a strike at the Brush Falcon works[1], and to provide Heather with the following background information.

‘In 1905 the Brush were having difficulty with their municipal customers for tramcars on account of the fair wages clause. This example is from the City Council of Manchester:

‘In letting contracts for ordering goods, preference shall be given to those persons or firms who pay to their workpeople the regular standard of wages obtaining at the time in the city or district. Compliance with this order shall be the essence of every contract, and no-compliance therewith, after notice to the Contractor, shall entitle the Corporation absolutely to determine the contract.’

London County Council (LCC) went even further and set out rates and hours which were inserted in and formed part of every contract. As a result, Brush failed to get LCC contracts and received complaints from Manchester. Two of Brush’s competitors went into liquidation and at the 1905 AGM it was announced that Brush had increased Rolling Stock and Tramcar orders had decreased from 1900 to 1904 by five times. Brush paid a 6% on preference shares and a 2.5% on ordinary shares. The workforce increased considerably, with some new recruits coming from the closed tramcar manufacturer G F Milnes. Union membership, hitherto rather low at the Brush, increased during 1905-06 and the United Union of Coach-makers felt strongly enough to present its demands for ‘Lancashire Wages’ to the Brush management who were paying 4s per week less than the competitor United Electric Car Co. at Preston. Brush contested that living rates were lower in Loughborough and refused to negotiate, and in September 1906 the Union brought its 200 members out on strike.

Brush recruited new coach makers who were intercepted by pickets at Loughborough Midland railway station: most returned home, their fares refunded by the union. Brush then organised trains for new recruits and those travelling in from Leicester to be shunted directly into the works. Beds were provided for anyone who wanted to live in. The strike lasted 6 months. Brush won and in January 1907 took back a quarter of the striking coach-makers on the old terms and a further 25% a month later. There were no more major strikes at Brush until 1925.’

The Lonsdale Hotel in Burder Street was opened on the 16th February 1898. It closed in 2001.

Find out about the history of trade unions and about how to read the history of old postcards.

Do you have any information you can add to this feature? If so, contact us at lboro.history.heritage@gmail.com.

[1] Information source: the Brush Electrical Engineering Company Limited and its Tramcars by J H Price, Tramcar and Light Railway Society, 1976.

Pottering about … Burleigh Hall

15 January 2021

In 1840, T R Potter published a collection of essays entitled ‘Walks Round Loughborough.’ Amongst these was a description of Burleigh Hall. Demolished in 1961, it was replaced by the Edward Herbert Building and part of Administration Building I of Loughborough University. A remnant of the former walled vegetable garden survives adjacent to Administration Building II.

The only nearby reminder of the Hall still standing is the gardener’s cottage, almost hidden from view now, as it probably was to T R Potter. The cottage has many interesting features for us but they were not matters to attract the attention of Potter or his readers.

Originally these essays had been written to occupy one column of a local newspaper. When they appeared in book form he added steel engravings to illustrate some items but sadly Burleigh Hall was not selected.

The walk opens with the approach from Loughborough along the Ashby Road.

| But to our walk. Taking the Ashby-road, the Catholic Chapel will suggest matter for reflection, to Mr Middleton’s Villa and Cottage Ornée will, perhaps agreeably, interrupt it. Burleigh Hall On the left is one of those mansions where the good old times are still fondly cherished. The Hall itself is a pleasing object, and such places are doubly pleasant in the prospect when we know them to be the abode of wisdom and worth. One may speculate on the origin of the name. Has the spot ever been honoured with the presence – or does its possessor claim kindred with – one of the greatest men that ever adorned the tide of times – the great Lord Burleigh? The Hall affords delightful sunset views – equal to any we have seen. The domain, pretty as it is, is sadly disfigured by a thing called a lodge, which abuts on the road, and which is, without exception, the most Finchley-Common looking structure ever erected in such a spot. Our amusement for the next hour must be poking in the hedgerows, where some rare botanical specimens may be gathered. The pedestrian will, however, do well to watch, from time to time, the ever-varying phases of the Forest, not undelighted will he be with such views as will present themselves. When we last took this walk, we had the pleasure of meeting Sir David Wilkie, enjoying con amore scenery, that strongly reminded him of his bonnie native hills. |

The Catholic Chapel is Saint Mary’s which, in 1840, was only what is at the present of the chancel. He mentions the Grove, a house built for the banker and landowner, William Middleton, in a version of the Italianate style. This house still stands but is much adapted to the rear and internally to meet the needs of students of the 20th century. One of cedars planted in the front garden has remained to remind us of the graceful ideas current in the early 19th century. It would be interesting to know the exact location, and whether any of the ‘Cottage Ornée’ survives.

Soon after this Potter mentions, however, that a thing disfigures the domain called a lodge. He also identifies it as the most ‘Finchley-Common’ structure. The lodge stood at the grand entry to Burley Hall. This building survives, hidden by trees and shrubs, and is part of Mumford Hall.

Finchley-Common might have been an allusion to Thackeray’s Vanity Fair where a snob refers to an item written by a washerwoman from Finchley as vulgar and unreadable. Potter implied a vulgar and ugly design.

Burleigh Hall in 1840 had the external characteristics of many classical gentry houses. Its location gave it panoramic views of the eastern style side of Charnwood Forest as well as views towards Garendon Park and across Loughborough to the hills of Cotes. In 1840 the property belonged to Miss Tate, a noted benefactor in Loughborough, whose support for the Public Dispensary (forerunner of the Baxter Gate Hospital) was acknowledged on many occasions.

Perhaps a visitor was Sir David Wilkie R.A., who was a great friend of Sir George Beaumont of Coleorton Hall. Beaumont was a major patron of the arts who contributed to the founding of the National Art Gallery. Perhaps Wilkie may be best known for his rather flattering portrait of King George IV entering Holyrood in full highland dress. However, Wilkie was a favourite artist of George III and William IV. He died in 1841.

Potter’s speculation about the name of the Hall arose from his wish to find a national hero with local associations. In fact, the name means the fortified place on the hill and was in use before Lord Burleigh became Queen Elizabeth I’s advisor.

Most of the Burleigh estate now belongs to the University and it still has some botanical treasures in its grounds.

This article first appeared in the newsletter of Loughborough Archaeological and Historical Society in Spring 2006 under the title ‘Pottering about Loughborough.’

In 1881, the Rev W G Dimock Fletcher wrote about the Burleigh estate in his ‘Historical Handbook to Loughborough.’ Read what he said about it here.

See what Burleigh Park looked like in the early days of the University’s ownership here.

Watch a film of the Leicestershire Yeomanry’s regimental sports event at Burleigh Park in June 1938 here.

Compiled by Alison Mott

Childhood Memories of Boxing Day

8 January 2021

I remember enjoying Boxing Day as much as Christmas Day. First stop was to see the Quorn hunt in the marketplace. A fine spectacle they were too, resplendent in their scarlet jackets. This meet was well supported by the people of Loughborough.

Then on to the drill hall in Granby Street to meet my grandparents, Jack and Mary Nix of 12 Thomas Street. There was a party laid on there for children – sandwiches, jelly and cake, and noisy games.

Looking back, it must have been horrendous for the adults. The room was big, or it seemed so at the time, with a wooden floor. Dozens of children running up and down, whooping and hollering. I remember it being great fun. Not sure if there was a bar there, if so maybe it helped the adults to cope.

My grandparents, Jack and Mary, were heavily involved with the Royal British Legion, one was secretary, the other treasurer. I believe at one time the hall was used by the TA before it moved to Leicester Road.

Granddad was a military man and believed everyone should serve some time in the armed forces. One year, he was chosen to represent the Loughborough branch of the Royal British Legion at the Royal Albert Hall’s Service of Remembrance. I was so proud to see him on television.

Grandad was born in Mapplewell, Yorkshire in 1873. He left school at the age of 13, worked down a coal mine in Barnsley until the age of 19. Then he joined the York and Lancs regiment. Fought in the Boer War, Matabele wars, World War One, and was in the Home Guard during World War Two. He died in 1963.

by Diane Ayres

William George Dimock Fletcher, a recorder of history

4 January 2021

William George Dimock Fletcher was born on 4th January 1851 in Handsworth, Staffordshire, the eldest child of John Waltham Fletcher and his wife, Elizabeth. At the time of William’s birth John Fletcher was curate of St James’ Church, Handsworth, but his career would see him and his growing family moving on to Coventry and then to Leicester, where he became Chaplain of Leicester Gaol.

As a ten-year-old, William boarded at Kings Heath School in Kings Norton, progressing as a teenager to Bromsgrove Grammar School in Worcestershire, where he won prizes for languages and for writing.

By the age of 20 he had moved to Loughborough to take up an apprenticeship with the solicitor John Woolley. William soon decided to follow a different career, however, enrolling at St. Edmund Hall, Oxford at the age of twenty-three to study for the Church. He was ordained as a Deacon in 1878 and as a Priest in 1879.

William began his ecclesiastical career with a short curacy at St. John’s Church, Hammersmith, followed by four years at Holy Trinity Church, Oxford. In 1881 he became parish priest at St Michael’s in Shrewsbury, where he also acted for a time as chaplain to Shrewsbury Prison. After nineteen years at St Michael’s, William moved a short distance away to Oxon Church at Bicton Heath, where he remained until his death.

William Fletcher was a member of Leicestershire Archaeological Society, Shropshire Archaeological Society and Natural History Society, the Society for the Parish Registers of Shropshire, and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries.

He was a prolific writer and a much-respected scholar, publishing pamphlets, papers and history books on the ‘genealogy and antiquities’ of the areas in which he lived, from his early twenties into old age.

Of interest to Loughborough are his collections of the town’s stories, published first as articles in the local paper and then collected together into books published by H Wills of the Market Place. His books contain memories and hearsay told to him first hand by people of the town, which would have been lost to modern times if William hadn’t recorded them. Whilst not always accurate (people having the habit of misremembering things and getting facts wrong) most of them have been proved to be true.

In old age, certainly, William was a much-respected scholar, sought out by other historians and scholars for information and advice, and is known to have preserved whole collections of historical information through translation and painstaking research. His last printed work, A Short History of Shelton & Oxon, was published in 1929 when he was 78 years old.

He kept up his connections with Loughborough throughout his life, donating collections of press clippings and other archives of relevance to the town’s history to the Library in his later years.

William G D Fletcher was married twice; firstly in 1881 to Elizabeth Arrowsmith of Shrewsbury, who died in 1931. William then married Gladys Clarke of Bicton on 19th November 1934. He had no children.

Sadly, William was injured in a traffic accident outside his home in Bicton on the first anniversary of his marriage to Gladys. He was taken to the Royal Salop Infirmary in Shrewsbury where he died from his injuries on 6th December 1935. Known affectionately as ‘the oldest clergyman in Shrewsbury’, William’s funeral at Oxon was conducted with a pomp and ceremony he would surely have appreciated, performed as it was by four clergymen: the Archdeacon of Salop, the Reverend E Moore Darling and the Reverend W E Y Thompson – Rural Dean of Shrewsbury; the graveside rites were performed by William’s younger brother, Canon James Fletcher[1].

William’s death was reported in newspapers across the country, including The Times. His old friends in Leicestershire Archaeological Society paid particular tribute to him, expressing their gratitude to a man without whom many interesting snippets of the town’s history would surely have been lost.

Alison Mott

[1] of Stratford in Sarum Cathedral, on the edge of Salisbury

On this day in Loughborough … 1st January 1900

1 January 2021

‘In an address given before the Wood Gate Young People’s Society, on the 1st January 1900, Mr Henry Godkin said ‘my mother[1] was born on Plough Monday in January, with snow and frost outside, and she has told me what fearful condition her mother was in that day.’

‘On Plough Monday, boys and men used to dress up in the most outrageous and horrifying costumes and were very rough on people who gave them nothing. They would force themselves into the houses, and you can imagine what a day of terror it must have been with those rowdy, drink-sodden, half-mad men. My mother remembers many such Mondays.’

Plough Monday is the traditional start of the English agricultural year and is generally the first Monday after Epiphany (the twelfth day of Christmas – therefore, the 6th of January.) It signalled a return to work following the Christmas festivities.

Traditions associated with Plough Monday vary from region to region but included hauling a decorated plough from house to house collecting money to support farm workers at a time of year when they were particularly badly-off.

Extract from: ‘Loughborough in the XIX Century’ by W A Deakin

Additional information sourced from Wikipedia.

Click here to see a recipe for a ‘plough Monday pudding’ traditionally made in Norfolk.

Compiled by Alison Mott

[1] Mrs Godkin would’ve been born in the early 1800s