Loughborough Parish Library (2): poor rates and bookplates

26 May 2023

It was 1761 when the new Rector James Bickham arrived at Loughborough with his luggage of books, books and more books.

His arrival coincided with the passing of Acts of Parliamentary enclosure in Leicestershire.[1] These occurred between 1759 and 1840, with most Acts passed between 1760 and 1790. Loughborough enacted these measures quickly: the open fields around the small town were enclosed by 1760.

For landowners, farming in severalty[2] increased the income from the land they owned. Farmers and landowners generally preferred to transform arable land into permanent pastureland for grazing cattle. The population of towns – including Loughborough – had grown significantly since the Middle Ages, offering a ready retail market for food produced at commercial scale; whilst their need for housing drove up the price of land on the outskirts, marking the beginning of urban sprawl.

This was not just profitable for private agriculturalists and property developers: Loughborough’s two schools, the Grammar School and the charity school for poor girls, the Blue Coat School, benefited from enclosure too as their endowments increased.[3] The income of the Grammar School trustees rose from £740 at the end of the 18th century, to £1,300 in 1819 and £1,6000 in 1831; the income of the Blue Coat School was £22 in 1745, £30 18s. in 1786 and £80 13s. 1d. in 1837, according to Bernard Elliott’s The History of Loughborough College School (1971, page 27).

What about the people who did not own land and had farmed for their subsistence on open fields, used commons for grazing their animals, and waste land for forage and fuel? Luckily for these people in Loughborough, Charnwood Forest remained unenclosed waste land until the end of the 18th century. Even so, enclosures removed an age-old public reserve. Life now depended on selling one’s labour alone.

Inevitably employment was not constant enough to keep all in work and people fell on parish relief[4] in larger numbers. Nationwide poor rates were customarily fixed by local parish officers. In Loughborough this duty fell to the town estate, who were twelve elected inhabitants and one executive officer, known as the bridgemaster.

Dorothy Marshall notes in her ground-breaking study The English Poor in the Eighteenth Century (1926) that whilst poor rates had been steadily rising over that century, the period 1760-82 saw a sharp rise in poor rates nationwide, “owing to the gradual and increasing growth of distress, and thanks to bad harvests” (page 79). At Leicester, Marshall writes, a rate worth £735 19s. 4d. in 1776 rose to £926 14s. 3d. in 1782.

In Loughborough the town estate had been running a workhouse for people who could not support themselves from as early as 1748, but workhouses notoriously failed to be lucrative and functioned mostly to contain people. Containment in the parish and shaming by the parish had been tried and tested strategies across communities in 17th century Britain. The Settlement Acts of 1662 and 1697 stipulated that a stranger could be removed from the parish if they had not found work within forty days and were to be returned to the parish where they had last resided (taken from Hungerford Museum Caring for the Poor). This was done to protect communities from paying poor relief for outsiders.

In 1694 “Badging” was brought in, whereby a pauper could get weekly relief only if they publicly wore a mark that identified their status. Paupers had to wear a cloth or brass “P” for “pauper”, the former made of red or blue cloth and stitched to the top of their right sleeve. Indeed, their entire family including all children had to wear the “P”, a symbolic practice linked to branding criminals in earlier centuries, which also made paupers highly visible, thus also discouraging forbidden activities such as begging. Any parish officer who dispensed relief to a poor person not wearing a badge could be fined 20s.

According to Steve Hindle’s 2004 study Dependency, Shame and Belonging: Badging the Deserving Poor, c.1550-1750, there were no documented county-wide initiatives to badge the poor in the East Midlands, but there were parochial initiatives to implement this method of control. Sutton Bonington is recorded as having badged the poor in 1731. Whilst this measure was resisted, in the context of its time it was consistent with wider practice such as obliging charity recipients like Loughborough’s Blue Coat School pupils to wear blue. The colour-coded blue coats and slips identified the schoolgirls as poor girls, albeit deserving ones, and prevented their families from pawning or pledging charity clothes for credit, as Hindle observes referring to a similar community (page 17).

Did the new Rector James Bickham have any experience of poverty to enable him to deal with real-life hardship? From the books he collected we know he read Jonathan Swift and Daniel Defoe, two authors who argued in their pamphlets from a core conviction that the poor were responsible for their condition and should overcome it through work. Swift published on this explicitly in his 1737 pamphlet A Proposal for Giving Badges to the Beggars in All the Parishes of Dublin, which is a less satirical and more practical follow-up to the infamous Modest Proposal of 1729. Bickham’s copy of this text is in the LPL, part of a multivolume edition of Swift’s works.

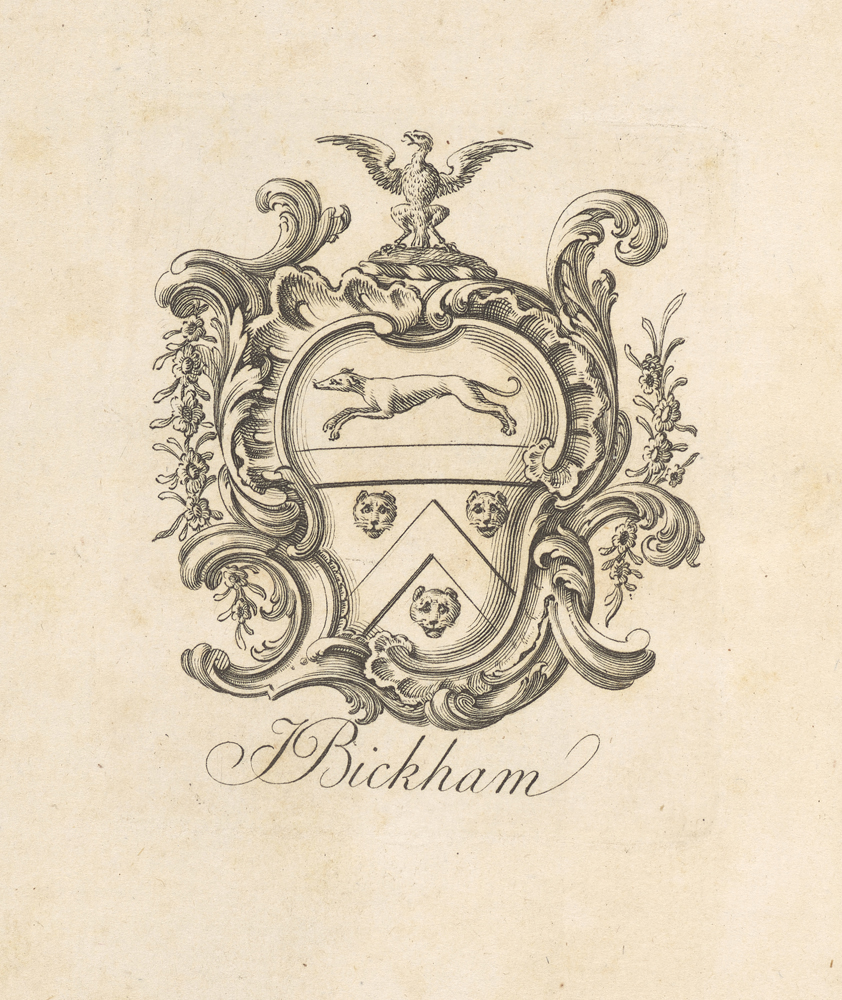

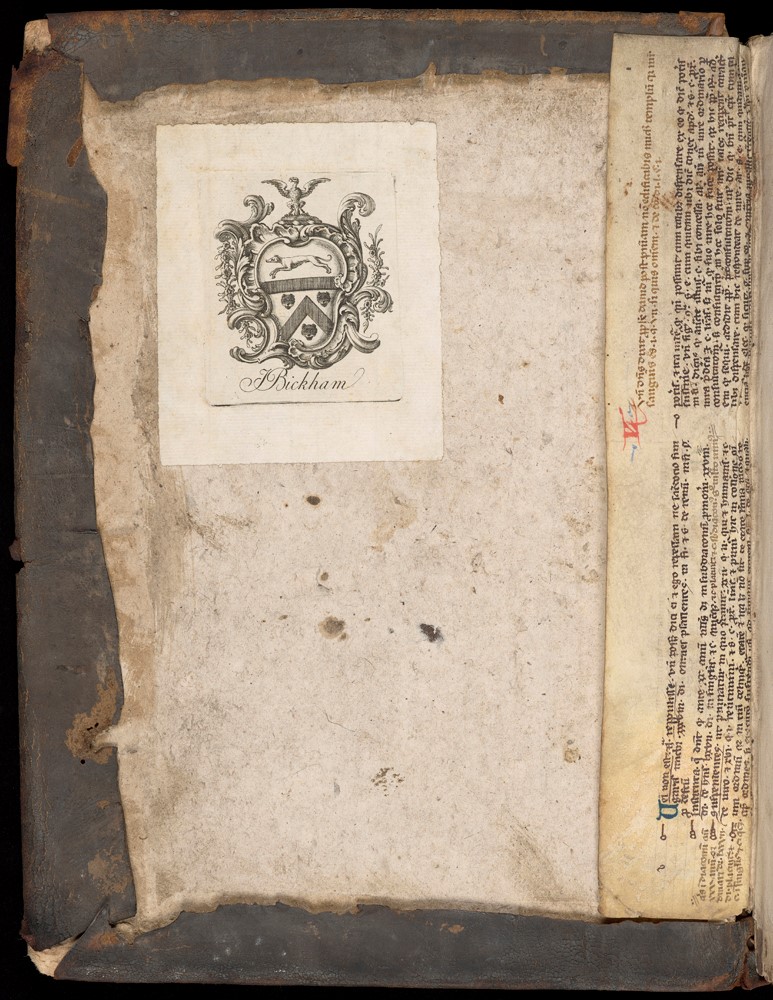

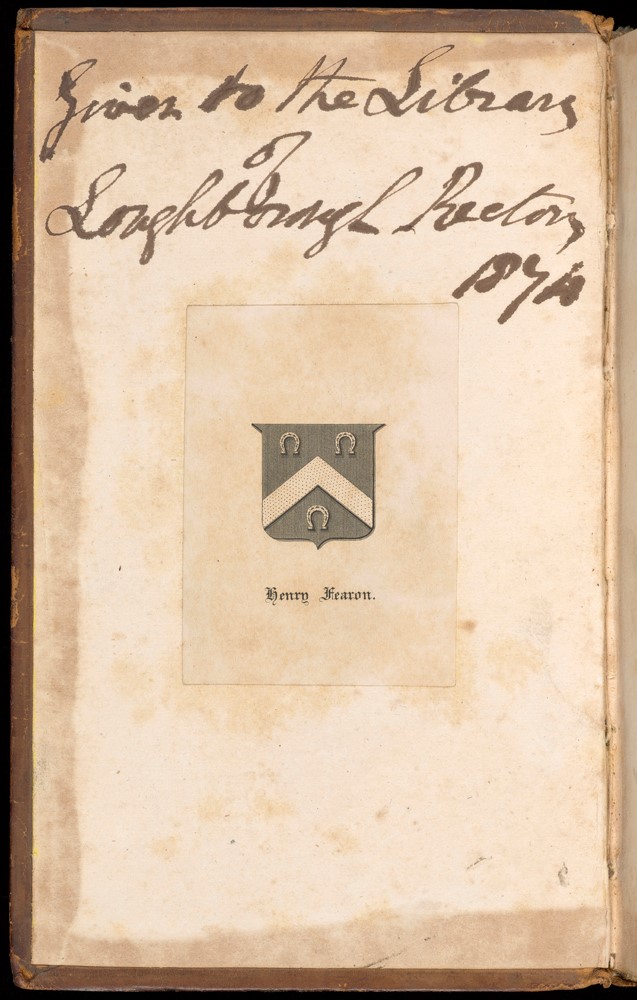

Whatever Bickham’s social views were, having lived all his adult life in College in Cambridge, it seems likely that his understanding of inequalities would be abstract. One could guess that Bickham would have associated the word “badge” with honour, first and foremost. Why? Because book collectors in the 18th century took to plating their books with their families’ coats of arms. The new Rector was distinctly fond of this genteel fashion: all his books bear bookplates engraved with his coat of arms and name.

A bookplate has a practical side. It acts as a silent tracker for copies gone astray and a block to sneaky appropriation. However, there is more to it. Beyond marking ownership of a physical object, a bookplate links a person’s name and pedigree to endurance in print.

Next blog: What can we glean from the Loughborough Parish Library about its maker, the rector James Bickham?

© Article written by Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

Resources:

Bernard Elliott, The History of Loughborough College School (1971)

Alfred White, A history of Loughborough endowed schools (1969)

Dorothy Marshall, The English Poor in the Eighteenth Century (1926)

Hungerford Museum, Caring for the Poor

Steve Hindle, Dependency, Shame and Belonging: Badging the Deserving Poor, c.1550-1750 (2004)

Jonathan Swift, A Proposal for Giving Badges to the Beggars in All the Parishes of Dublin (1737) in Miscellanies (1745), Volume 9. Loughborough Parish Library, PR3722 .M5, barcode 1008382390

_____________________________________________________________________________

© Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

© Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

© Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

© Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

[1] This was the enclosing – or fencing off – of areas of common land which had previously been under the control of the lord of the manor, but which ordinary townsfolk had had the right to make use of for, for example, grazing livestock and growing food.

[2] Severalty is the individual right of ownership, not shared with any other person.

[3] An endowment is a financial gift bequeathed in a will – often to a hospital or educational organisation – which will provide a continued income to those receiving it. Both the Grammar School (for boys) and the Blue Coat School (for girls) were bequeathed the rental income from lands in and around Loughborough, and as those lands became more valuable over time, their rental income increased.

[4] An unemployment benefit given out by the parish.

Previous post: Loughborough Parish Library (1): what it is and where it is now

Next post: Loughborough Parish Library (3): curator James Bickham (1719-1785)

Loughborough Parish Library (1): what it is and where it is now

19 May 2023

James Bickham (1719-1785) was a Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and clergyman, scholar and fifteenth archdeacon of Leicester. He was presented the rectory of Loughborough by his college in 1761 and became archdeacon of Leicester in 1772. Bickham retained both offices until his death in 1785, whilst residing in the Rectory, a medieval hall-house located beside All Saints Church, Loughborough. The Old Rectory is now a museum managed by the Loughborough Archaeological & Historical Society.

After graduating in 1740/1, Bickham was a Fellow of Emmanuel College from 1743-1761 and pursued higher degrees during his Fellowship. When he arrived at Loughborough he brought with him his collection of several hundred books, gathered since childhood, according to his interests. By the time he died it numbered 641 titles.

We know this because in 1786 Bickham’s successor had a list made of the books as found in the Rectory, presumably to keep them separate from his own collection. Of the 641 titles listed, 420 titles have survived to date. It is a rare occurrence for libraries to retain their integrity over centuries. Bickham recognised the value of his collection and providently handed in his will responsibility for the collection to his successors at All Saints:

“I give all my printed Books to the Rectory of Loughborough for the use of my Successors for ever except two Volumes of Miltons prose works by Birch which I desire the Bishop of Worcester to accept.”

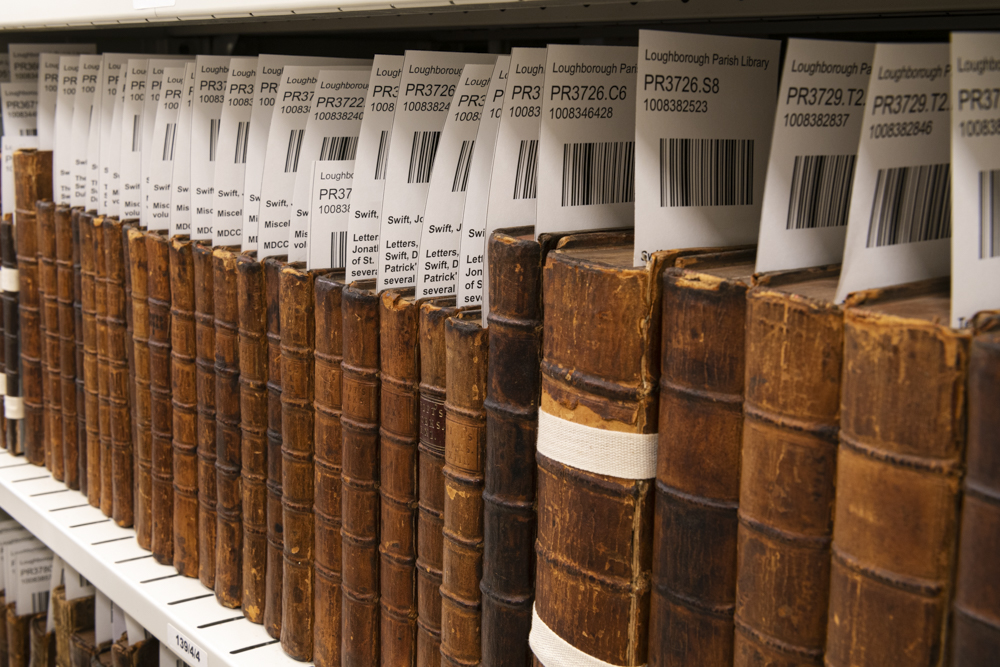

The books were originally kept in the medieval Rectory, then in the parvise of the church for some years, secluded but under threat from a leaky roof. In 1967 the collection was deposited in Loughborough Technical College. It moved to Loughborough University in 1987, then to Manuscripts and Special Collections at the University of Nottingham in 2012. The books have been here ever since.

In 2022 they were catalogued at full level of the rules of descriptive cataloguing of rare books and can be browsed online in the University Library’s catalogue NUsearch. By typing LPL into the search bar, short for Loughborough Parish Library, and filtering the results to Manuscripts and Special Collections (see filter in the pane on the right), the records of circa 500 books will appear in the hit list.

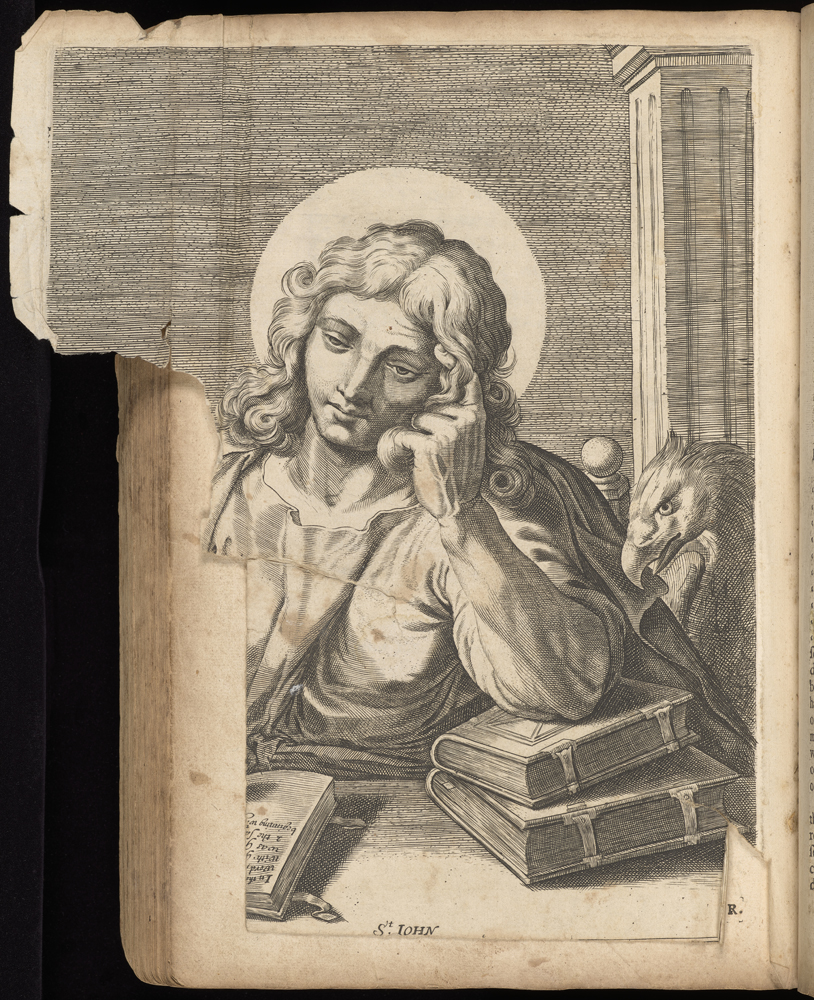

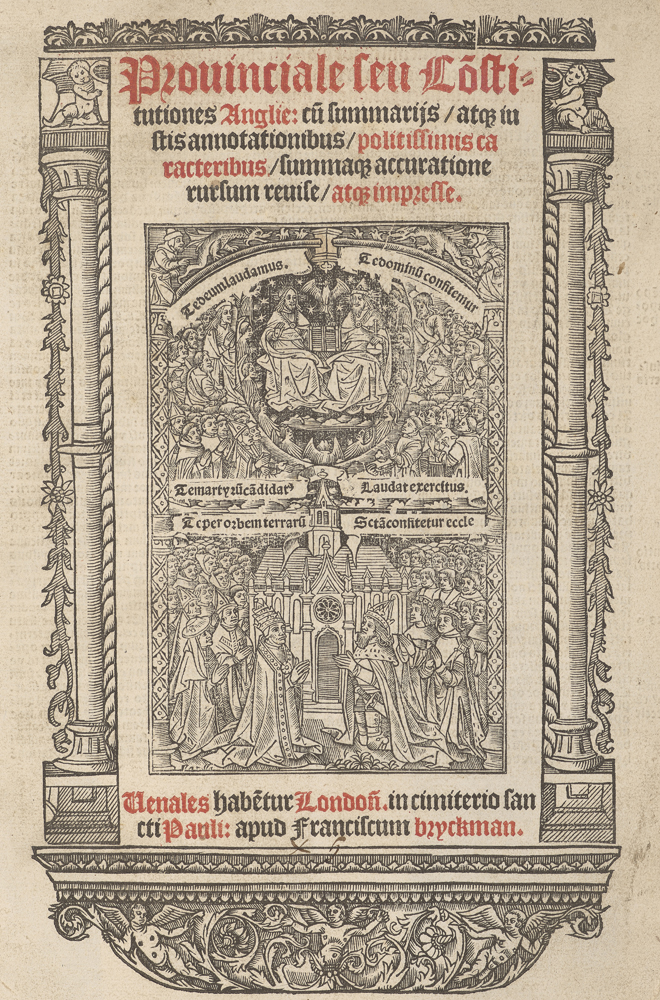

Approximately 100 books which were not collected by Bickham are included in the collection forming the LPL. Some of these presumably belonged to the church, for example, a copy of The Paraphrase of Erasmus on the books of the New Testament, published in 1548, bound in the original 16th century boards in the diaper design. It lacks Bickham’s bookplate and was not listed in the 1786 catalogue, however, the Inventory of such goods as doe now belong unto the Church this yeare 1619, made by the churchwardens Edward Cranwell and Francis Stable, lists under 3: Erasmus his paraphrases upon the Evangelists. This is likely to be the surviving copy in the LPL.

Books were also added by Bickham’s successors such as the rectors William Holme and Henry Fearon or by parishioners. We know this because Holme annotated the 1786 catalogue and added in titles of books he had contributed to the collection; Fearon inscribed 12 books with the note “Given to the Library of Loughborough Rectory 1874”. As for private donors, in 1916 a parishioner gifted a copy of The Leicestershire harmony (1759) to the rector Thomas Pitts with a note stating that the book is “worthy of a place in the Rectorial Library”.

It is also a rare occurrence for libraries to stay unforgotten for centuries. Their usual fate is that exemplified by two libraries owned by rectors of All Saints, both incidentally childless and published authors in their lifetime, George Bright and Samuel Blackall. According to David Pearson’s research on Book Owners Online –

“Bright’s lengthy will, mainly concerned with distributing property and money around his relations and servants, has no mention of books. His library was sold by retail sale in London, beginning 13 July 1697. No catalogue survives, but the sale was advertised in The Post Boy as ‘a curious collection of Greek and Latin fathers, historians, philologers, poets, &c with a large collection of Hebrew and other oriental books’. […] None of Bright’s books have been identified.”

Samuel Blackall, on the other hand, mentions his books in his will, leaving them to his two favourite nephews. Both Bright’s and Blackall’s libraries vanished in the mists of time.

The Loughborough Parish Library can be viewed by all members of the public in the Reading Room at the University of Nottingham’s Manuscripts and Special Collections. Find out here about our opening times!

Next blog: What was Loughborough like in 1761 when the Rector settled into the Old Rectory with his books?

© Article written by Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

Resources used:

Margaret Baker, The life and times of the Rectors of Loughborough (2012)

Lynne Dyer, Revd James Bickham’s Library, Sunday, 26 February 2023

_____________________________________________________________________________

Previous post: Loughborough Parish Library (intro)

Next post: Loughborough Parish Library (2): poor rates and book plates