Rectors and Vicars explained

30 June 2023

So, what exactly is a rector?

A rector in the Church of England was (and continues to be in parishes such as Loughborough) essentially a parish priest, with the same duties as those carried out by a vicar, a role we’re perhaps more familiar with today.

Historically, those duties have included –

- leading morning and evening prayers;

- delivering sermons in the regular round of church services and

- additional sermons on saints days and holy days;

- officiating at christenings, marriages and funerals;

- attending meetings to deal with parish matters, and

- supporting the needs of parishioners in the community, including the poor.

The difference between the post of rector and vicar comes down to status, with a rector considered of higher social standing than a vicar and the income – or stipend – he received reflecting that difference.

Parishioners covered the cost of their parish priest through payment of a tax – known as a tithe – on the crops they grew, the animals they raised and the goods that they made.

The word ‘tithe’ – from the Old English word teopa – means ‘one tenth’, and this was the percentage each parishioner must hand over to their local representative of the Church of England from everything they produced. Tithes were a legally enforceable tax and all parishioners had to pay them, whether they followed the protestant faith or not.

The wealthier those parishioners were, then, the greater the amount of goods their parish priest received, and the wealthier he himself became as a result. The broad, flood-enriched meadows of Loughborough parish easily sustained flocks of sheep whose wool was turned into cloth and sold as far afield as Calais. Because of this, local landowners became very rich and in turn, so did the local Rector. As mentioned elsewhere, the ‘living’ of Loughborough was indeed a very handsome one.

Initially, tithes were collected largely as goods, a one-tenth portion of the annual harvest and stored by the priest in tithe barns built for the purpose.[1]

It’s been said the idea behind paying the clergy like this was to link the fortune of a cleric with those of his parishioners, so that all did well when the harvest was a good one and suffered equally when it was bad. Whether this was originally the intended purpose or not, cases of clergymen struggling to get people to hand over their tithes are well documented (including for Revd Bickham).

To complicate matters, there were two levels of tithes –

- greater tithes, which included everything that arose from the ground – wheat, oats and barley, for example, as well as hay and wood, with even windfall apples being taxable[2], and

- lesser tithes, which were all things nourished by the ground – the produce of livestock such as eggs, milk and butter – and the livestock itself – chickens, lambs, pork and the like.

As you might guess, the higher-statused rector was entitled to receive tithes from both categories – the greater and the lesser, whilst a vicar only received the lesser tithes – about a quarter of all the tithes collected in the parish.

This didn’t mean that a parish with a vicar got off lightly, however. The full ten percent tithe was still collected in, but with the remaining three-quarters being paid to whoever owned the advowson for the parish (which as stated previously, might be the lord of the manor, a wealthy private individual or an institution such as a university). Another very good reason for buying up an advowson if you were able to.

So, as a result of the difference in the tithes they were entitled to receive, clergymen with the title of rector tended to be wealthier (and by association, more powerful) than those who were merely vicars.

Interestingly, these differences are reflected in the titles themselves. The word rector is related to the words right and rectify, signifying that the role of the rector was to lead his parish in the right direction.

The word vicar comes from ‘vicarious’ – from the Latin noun vicis, meaning ‘stead’. The oldest meaning of vicarious, dating to the first half of the 1600s, is ‘serving instead of someone or something else’.

Rectors had an additional advantage over vicars in that parishes headed by a rector usually had farm land – known as glebe land – designated for the cleric’s use and thereby providing additional income from crops and livestock, or from rent.[3] In return, the rector was responsible for paying for any repairs that were carried out to the chancel[4] in the church, an obligation not expected of a vicar.

Well-paid rectors and vicars had enough disposable income to employ a lower-ranked clergyman to carry out much of the day-to-day work of the parish on their behalf. These were known as a curate, a word meaning to be responsible for the ‘care or cure of souls.’ Technically, then, any clergyman could be classed as a curate, though in reality the expectations on the roles were very different.

Alison Mott

[1] This was changed to a monetary payment of their value in the Tithe Act of 1836.

[2] From ‘Tithes and the Rural Clergyman in Jane Austen’s England’ by Eileen Sutherland, on the website of the Journal of the Jane Austen Society of North America, sutherland.pdf (jasna.org) [accessed 23.6.23].

[3] From the Latin gleba or glaeba, meaning clod, land, soil

[4] The area behind the altar.

Bickham bides his time

23 June 2023

Before James Bickham came to Loughborough to take up post as Rector of the parish, he’d been waiting for a living for some time, ‘kicking his heels’ for 20-odd years as a Fellow at Emmanual College, Cambridge, a two-hundred-year-old university established specifically to educate Protestant preachers.[1]

As noted in the previous blog, a career in the Church of England had historically been considered a desirable option for a young man with limited funding but a decent level of education. The Church was (and continues to be) a hierarchical institution much like any other, made up of various levels of personnel, each receiving a salary in proportion to rank and status.

The post of Fellow at Emmanual College largely involved the teaching of undergraduate students – all male at that time, and all destined for the Church – along with some administrative and governance duties. It wouldn’t have been a highly paid post, though Bickham is likely to have ‘lived in’ alongside the students and therefore had his food and accommodation costs covered.

More interesting to modern-day readers, perhaps, is that during this era Fellows weren’t allowed to marry, and for Bickham to have waited for a parish for so long, deferring marriage to his long-term sweetheart in the process, he must have been confident that the living of Loughborough would one day be his. Or perhaps, as Ursula Ackrill has surmised, it’s simply that Bickham enjoyed the protected, scholarly life at Cambridge so much he was reluctant to quit it for a post in a parish, with the routine and hard work, difficulties, politics and intrigues to be navigated and overcome that went with it.

There was no retirement programme for clergy back then, particularly for those without an independent income to retire on, and clergymen generally remained in post until they died, no matter how old or ill they became, their duties carried out by a subordinate if they were too unfit to fulfil them themselves.

Bickham’s predecessor, the Revd Thomas Alleyne, whom he may possibly have met on his visit to the town in 1758, was only in his fifties but had been ‘afflicted with the gout’ for many years. He died in Bath in July 1761, leaving the way clear for Bickham to have the parish.[2]

It seems likely James Bickham will have been promised the living at Loughborough by someone influential at Cambridge, though it’s not known, now, who that might have been and why they favoured Bickham.

Whatever the circumstances of how and why he acquired it, with a stipend of more than £400 per annum – equivalent to almost £110,000 a year today – it would definitely have been worth the wait. [3]

(Image in ‘Caricature History of the Georges’, Pub. Chatto and Windus, Piccadilly, 1876.)

Alison Mott

[1] From ‘History of the College’ on website of Emmanuel College, [accessed 23.6.23]

[2] ‘The Rectors of Loughborough’ (1882) by William George Dimock Fletcher, on Google Books website Google Books website. Gout is the acute onset of inflammatory arthritis caused by the buildup of uric acid in the blood. Untreated, it can lead to joint and bone damage, heart, lung and kidney disease and result in premature death. Ref. Healthline website.

[3] See CPI inflation calculator here.

See previous post here.

The ‘Church Living’

16 June 2023

Revd James Bickham arrived in Loughborough in 1761 to take up the ‘living’ as rector of the parish and incumbent[1] of the church of St Peter and St Paul (now known as All Saints with Holy Trinity) – one of the major churches in Leicestershire.

Throughout time, to be a clergyman in the Church of England has meant to hold a respectable and influential position within an establishment at the heart of the governance of the country.

Historically for many in the clergy, the post came with free accommodation – a house to live in and raise a family – along with a secure stipend, or salary, to feed and clothe them with, both a very desirable thing in a time when there was no expectation on the state to house the homeless or top-up lack of income with benefits of any kind.

Added to that, the work of a cleric wasn’t the physical, manual work those at the lower end of the wealth scale were mostly required to do in order to earn a living. To be a clergyman required a certain skill-set, certainly – a particular level of education, for instance, at a time when schooling was neither free nor available to everyone, and at minimum an outward appearance of complying to the principles of the Christian religion as laid out in the Bible. But for the most part, ‘work’ as a clergyman offered a settled, sedentary and routine existence, with opportunities for socialising, reading and reflection and – at the higher levels particularly – a comfortable day-to-day life.

The role came with many benefits such as status within the community, and the opportunity for progression through the ranks for those with the right skills and attitude – and, most importantly, connections – to take them. A job worthy of an educated gentleman, therefore, traditionally seen as suitable for the second sons of titled or wealthy families who, because of primogeniture[2], had little or no inherited money of their own to live on. As such, a ‘church living’ was looked on in practical terms, sought more as a way to secure a life-long income than as a ‘calling’ to share the word of God (though there were undoubtedly clergymen who would have had this calling, too).

Church livings were handed out through patronage, or the support of someone with wealth and influence, who often owned the right to decide on the postholder for a parish. These rights – known as advowson – often belonged to titled families and wealthy landowners, to Bishops within the Church of England and even to prestigious universities. In Reverend Bickham’s day it was possible to sell an advowson to others, and common for them to be bought and held ready for a friend or relative to take up when they were old enough or the current post holder moved on.

And as the Church was a hierarchical institution, there were different levels of livings within it to be bought, sold and granted by patronage to an educated gentleman in need of an job. So, back we go to the question of Revd Bickham and what brought him to Loughborough to be rector.

(Continued here)

Alison Mott

[1] A term meaning the holder of a post or office.

[2] Primogeniture is the custom of passing a deceased person’s entire wealth to their firstborn legitimate child (generally males) rather than sharing it out amongst all their children.

Loughborough Parish Library (3): curator James Bickham (1719-1785)

2 June 2023

His library tells us that the Rector James Bickham earned his learning through hard work.

We know he loved books: he bequeathed his library to his successors and left specific books as a gift to a friend in his last will and testament. Bickham also continued to acquire new publications until the end of his life. In 1785 he added two new books, a presentation copy of discourses by Thomas Balguy, Archdeacon of Winchester, and a volume of poems by Milton, both ©1785.

However, we see conclusive evidence that Bickham worked hard at his studies when we examine three books that have survived in the library. They are a Greek Grammar, a Latin book on public speaking by the Roman author Quintilian, and a modern treatise on law.

From the date of their publication, it can be assumed that Bickham used them as an undergraduate at Emmanuel College. The leaves of printed text are interleaved with blank leaves, a popular fashion of binding for people who used texts for study. In Bickham’s three college textbooks the blank leaves are covered with handwritten practice tracts of translation, vocabulary, commentary, and copied-out phrases.

We know that after graduating in 1740, Bickham became a Fellow of Emmanuel College from 1743-1761. He obtained this job thanks to his hard-earned erudition[1]. This Fellowship appears to have been his sole source of income.

We know that Bickham waited until he was aged 42 to marry the woman he loved. In 1761 Bickham arrived at Loughborough a bachelor, but was within three months married to Sarah Williams, his long-standing lady friend from Cambridge. Fellows were forbidden to marry, and it seems likely that Bickham could not afford to resign his Fellowship.

Emmanuel College had advowson – that is, the right to appoint members of the Anglican clergy for a vacant benefice[2]. However, this depended on a benefice becoming vacant upon the death or, more rarely, resignation of the incumbent[3]. It appears that Bickham had no other route, such as a wealthy patron or influential backer, beside the hope that college would provide him with a living.

However, it is also possible that he enjoyed the scholarly life in college and gave it up only for one of the richest benefices. Local historian Margaret Baker discovered in her research that in 1758, Bickham had been sent by his college to Loughborough to report on the effect the proposed Enclosure Act would have on the glebe lands of All Saints. In 1761 Bickham accepted Loughborough at the same time as the Enclosure Acts were passed.

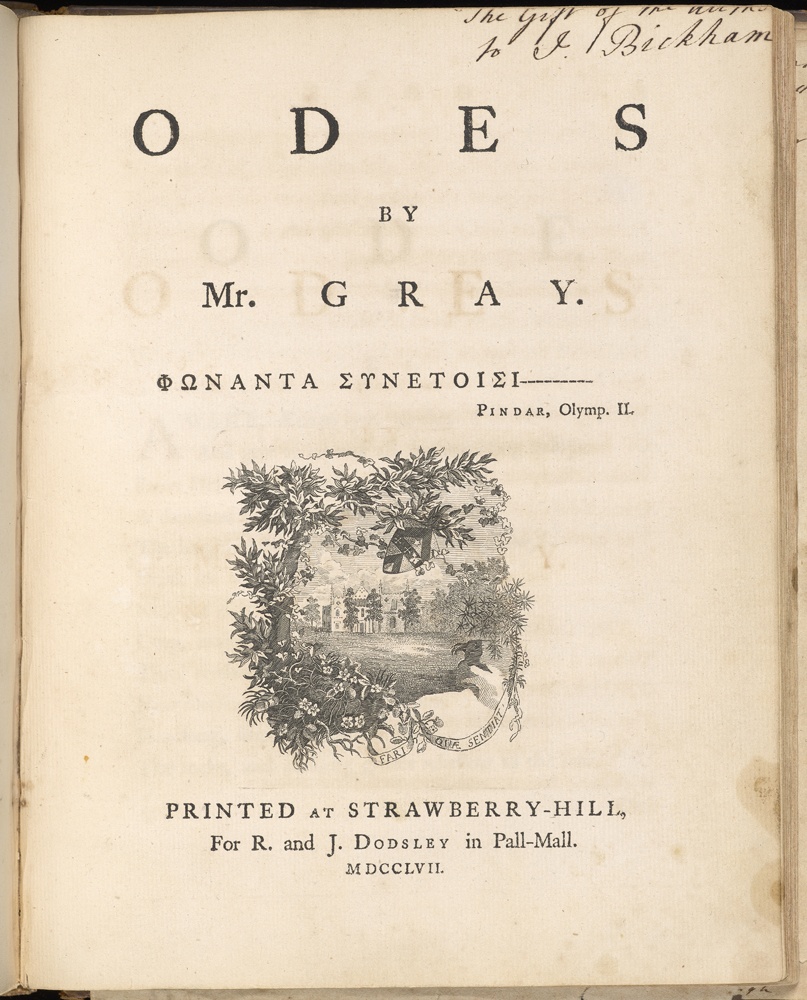

Bickham’s old friends from Cambridge, who like him vied to secure positions in the Church (William Mason, poet and later canon of York Minster and Richard Hurd, author of essays and later bishop of Worcester) or struggled to remain employed in college (Thomas Gray, the poet best-known for Elegy in a Country Churchyard), gossiped specifically about the wealth of his benefice. Thomas Gray wrote to William Mason: “Jemmy Bickham is going off to a living, better than £400p.a., somewhere in the neighbourhood of Mr Hurd and his old flame, that he has nursed so many years, goes with him. I tell you this to make you pine.”

The reality of being a Rector at All Saints took Bickham away from reading his books. Margaret Baker suggests that because of Loughborough’s enclosure, people who fell on hard times did not pay their tithes[4]; consequently, Bickham filed in his first decade as Rector ten suits against parishioners, to collect his dues.

In the following decade Bickham undertook lengthy and expensive repairs to the Rectory, which he financed himself[5] as was his duty as Rector. As archdeacon of Leicester, Bickham completed visitations between 1773-1779 to all churches in his purview[6] and wrote detailed memoranda requesting improvements to the buildings, probably drawing on lessons learned from his restoration work in the Rectory, as well as calling to order slack and impious practices such as schooling children in the church, neglected vestments[7] and books.

His diligence and rigour in delivering his duties were noted by historians. Yet at the same time we note that he never published anything. In his last will and testament, Bickham specifically asked his executor to burn all his sermons, letters and papers. In fact, were it not for annotations left behind in books, we would have no personal statement from Bickham beside the instructions made during church visitations – and his testament.

Gray, Mason and Hurd left lasting bodies of published work behind. Bickham, however, did not. He was in awe of his writer friends, that much we can surmise. Remember the two volumes of Milton’s prose which he gifted to Hurd in his will? They are deluxe editions, worth considerably more than the four books Hurd gifted him, of which two were duplicates from Hartlebury Library, a library for which Hurd was custodian – not creator. Weeding [out] duplicates is a basic management measure in looking after library collections.

Hurd was Bickham’s junior by one year and both had matriculated as sizars at Emmanuel College. A sizar is, according to the glossary on the University of Cambridge’s website, “a student originally financing his studies by undertaking more or less menial tasks within his College and, as time went on, increasingly likely to receive small grants from the College”. Gray, on the other hand, had gone to Eton College before matriculating at Peterhouse, Cambridge, as a pensioner (meaning a fee-paying student).

As an undergraduate Bickham earned himself a reputation as a prize-fighter and it is tempting to imagine Gray “managing”, or rather running a book, on the talent of the slightly younger sizar. Bickham was a gifted linguist, not just writing freely in Latin, as we can glimpse from his marginalia, but collecting Don Quixote in both Spanish and Italian, alongside Italian editions of Tasso, and Machiavelli, to name just two of his favourite Italian authors. Yet we do not know whether he travelled abroad.

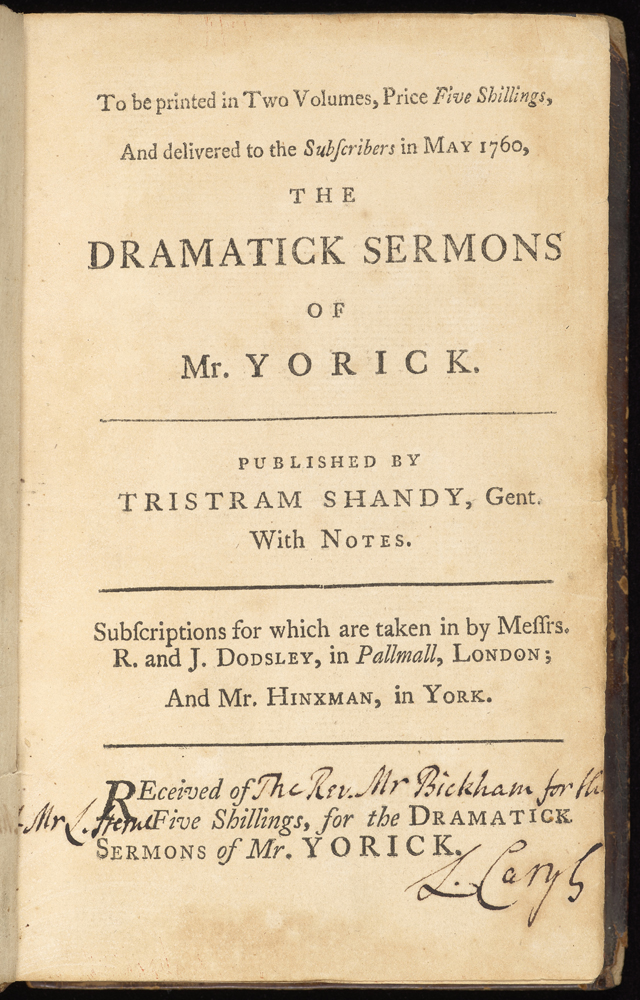

What is certain, is that Bickham would have seen his friend Gray depart in 1739 on his Grand Tour to Italy and France at the invitation of Horace Walpole, from Gray’s Eton circle of friends. With Horace Walpole, son of Prime Minister Robert Walpole, Gray spent two years abroad. It was not extravagant for middle-class clergymen like, for instance Lawrence Sterne, to embark on a Grand Tour. In Jonathan Swift, whose works Bickham collected avidly, and in Sterne, whose The Sermons of Mr. Yorick Bickham obtained by subscription, he beheld two leading lights of the literary world who had great careers in the Church just the same.

In the critical comments Bickham wrote in page margins and on blank leaves, he comes across as a frustrated critic, whose high standards are not being met by others. Further research is needed to confirm whether Bickham was being original, or whether he copied out paragraphs from other sources such as periodicals. Even if he was copying, however, his choice of quotes speaks of his character also:

- Flyleaf of Quintus Curtius Rufus’ 1705 Latin edition of the deeds of Alexander the Great inscribed in James Bickam’s hand: “Quintus Curtius is generally esteemed as an author rather qualified for a declaimer, than an historian, who took more pains to adorn his style & finish his periods than give a true & faithful account of things. Arrian’s History of Alexander is much preferable.”

- Inscription in Joseph Hall’s 1753 edition of his Virgidemiarium by Bickham, critiquing the author: “Which for him, who would be counted the first English Satyr, to abase himself to, who might have learn better among the Latin & Italian Satyrists & in our own poor Tongue from the ‘Vision & Creed of Pierce’s Plowman’, besides others before him, manifests a presumptuous undertaking with weak and unexamined shoulders. […]”.

- Finally, prefacing Bickham’s copy of the play The Rehearsal by George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, a 17th century author, is another biting commentary. It draws on The Rehearsal’s satire, aimed at John Dryden, England’s first Poet Laureate, and possibly critiques 18th century contemporary poets, foremost the unnamed Poet Laureate, possibly William Whitehead (1757–85): “To see the incorrigibleness of our poets in their pedantick manner, their vanity, defiance of criticism, their Rhodomontade & poetical bravado, we need only turn to our famous Poet Laureate (the very Mr. Bays himself) in one of his latest and most values pieces […]”. If Bickham wrote this, he would have been aware that his friend Gray famously declined the position of Poet Laureate in 1757, when it was offered to him before going to Whitehead.

Beside such harsh criticisms, Bickham’s books contain numerous marginal corrections like proof-reader’s notes, which pick out typos, or change the meaning – not obviously for the better – by suggesting alternative words. Bickham “corrects” authors of unassailable status as well as lesser-known names. Ultimately, though, we do not know why Bickham shied away from becoming a published man of letters.

As for the works of his friends Gray, Mason and Hurd, Bickham carried a torch for them. He inscribed the title pages of books gifted to him clearly as “a gift from the author” and had Gray’s Elegy bound together with Mason’s Elfrida and a poem by Thomas Francklin, a Cambridge contemporary, as if in a reunion edition of old friends. Bickham probably never saw his college friends again, but he kept their books. Bickham’s legacy is this collection of books which, as we shall see in the next blog, encapsulates the tensions of his age, caught between remnants of Medieval scholastic traditions and the pressure to educate people across classes and genders for modern times.

Next blog: Which side is the LPL on in the battle between the ancients and the moderns?

© Article written by Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

Resources used:

Paget Toynbee and Leonard Whibley, Correspondence of Thomas Gray Volume 3 (1935)

Margaret Baker, The life and times of the Rectors of Loughborough (2012)

W.A. Pemberton, The Parochial Visitation of James Bickham D. Archdeacon of Leicester in the Years 1773 to 1779 (1985)

[1] Knowledge gained through learning/scholarship.

[2] An official role within the church, along with the income and other assets (such as a house and farmland) which went with it.

[3] A person holding such a role.

[4] Tithes were originally a one-tenth percentage of all agricultural produce which households were required to hand over to the church to support the local clergy. An act of parliament in 1836 converted this tax to a monetary payment. In effect, this was Bickham’s income, and anyone failing to pay their tithe reduced that income. (Taken from website of nationalarchives.gov.uk)

[5] Bickham paid for the renovations from the income he received as rector. It wasn’t uncommon for the clergy to resist making repairs and improvements to the houses they lived in but didn’t own, given that they could simply save the money these cost for their own personal use.

[6] Area of responsibility

[7] The garments worn during religious services by the clergy, their assistants, choristers, etc

Loughborough Parish Library, PR3548.M2, barcode 100834608X.

© Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

Loughborough Parish Library, PR3714.S3, barcode 1008382229.

© Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

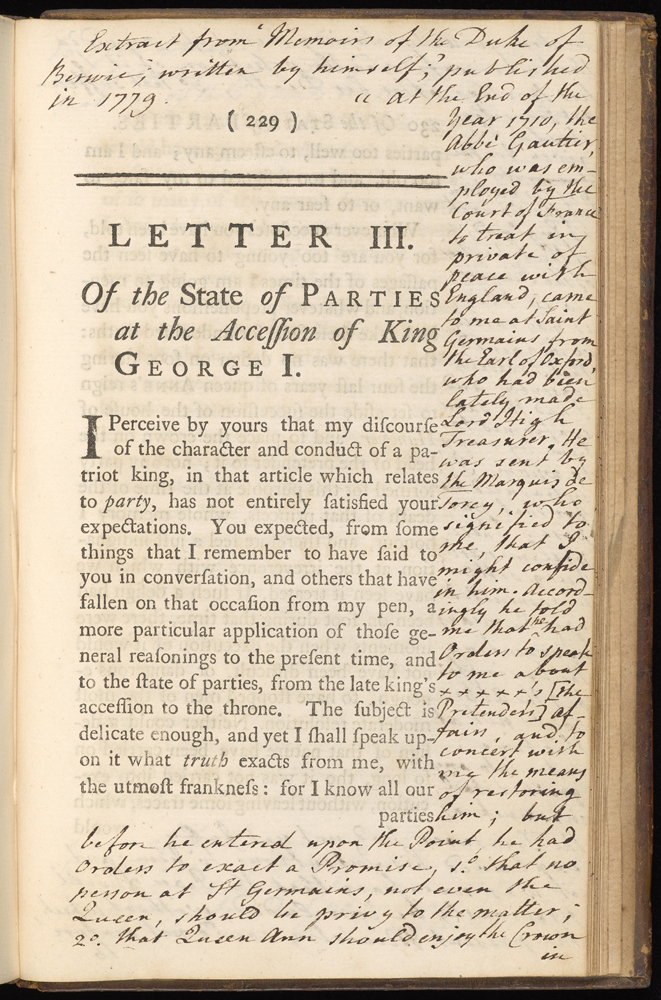

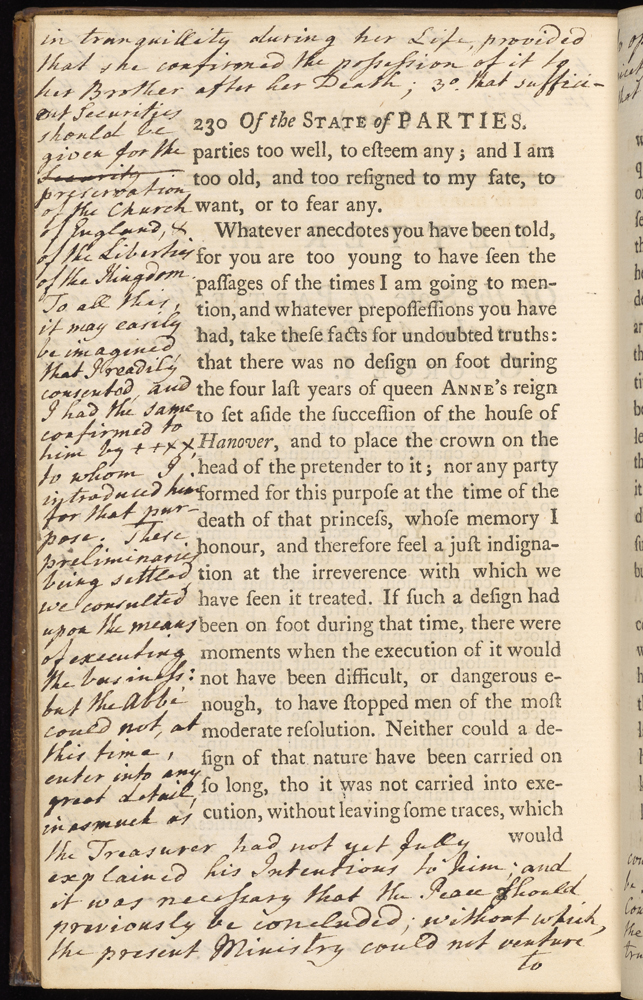

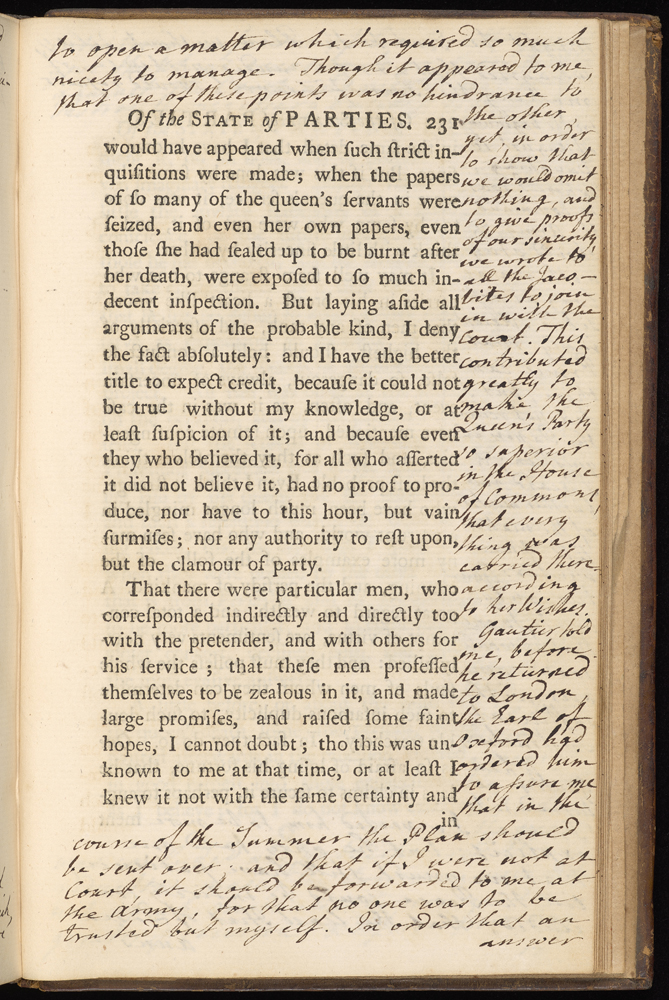

Three pages from a book of political philosophy with margins written in by James Bickham. He is copying from another text, ‘Memoirs of the Marshal Duke of Berwick’ (1779), to use as a parallel reference.

Henry St John, Viscount Bolingbroke, Letters, on the spirit of patriotism, on the idea of a patriot king, and on the state of parties, at the accession of King George the First (1749). Loughborough Parish Library, DA501.B6, barcode 1008382597.

© Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

Previous post: Loughborough Parish Library (2): poor rates and book plates

Next post: Loughborough Parish Library (4): the battle between the Ancients and the Moderns – which side is the LPL on?