Charnwood Ghost stories

20 October 2024

- The ruins of one of the buildings of Grace Dieu priory

- The Old Rectory in Steeple Row, Loughborough, which some people believe to be haunted.

It’s the time of year when thoughts turn to ‘ghoulies and ghosties and long-legged beasties, and things that go bump in the night.’ Or in other words, to the festival of Halloween, also known as All Saints’ Day.

Stories of ghosts abound across the country, with many locations designating themselves ‘the most haunted in England’.

Loughborough and the surrounding area are no exception, with a multitude of pubs and buildings claiming to have supernatural ‘residents’, ghosts reported in the old magistrates court on Woodgate, and a well-publicised supposed haunting of a house in School Street.

The ruins of Grace Dieu Priory, a 13th century Augustinian nunnery in Thringstone, claim to have a plethora of presences, amongst them the poet William Wordsworth and a more humble white lady, who is said to stand at the nearby bus stop and then disappear as buses draw near.

Bradgate Park is said to be traversed by a coach pulled by four black, headless horses, whilst Lady Jane Grey is believed by some to be so fond of Bradgate House that her spirit has decided not to leave it.

Ghost hunters at Donington le Heath Manor recently claimed to have recorded the voice of King Richard III and both Kegworth Village and the Great Central Railway are proud of their ghosts

Whether ghosts are real or not is a matter of personal opinion and people will argue each side of the case till the end of time. One thing is for sure, however, the topic has fascinated people for thousands of years and there’s no shortage of scary stories to entertain people with on a dark, windy All Hallows Eve!

Discover more:

Read a blog post by John Rippin, former editor of the Loughboorugh Echo, about the reported ghosts of Loughborough.

Find out about Leicester’s Most Haunted.

Buy a book about the history of Grace Dieu Priory or stories of it’s Ghosts.

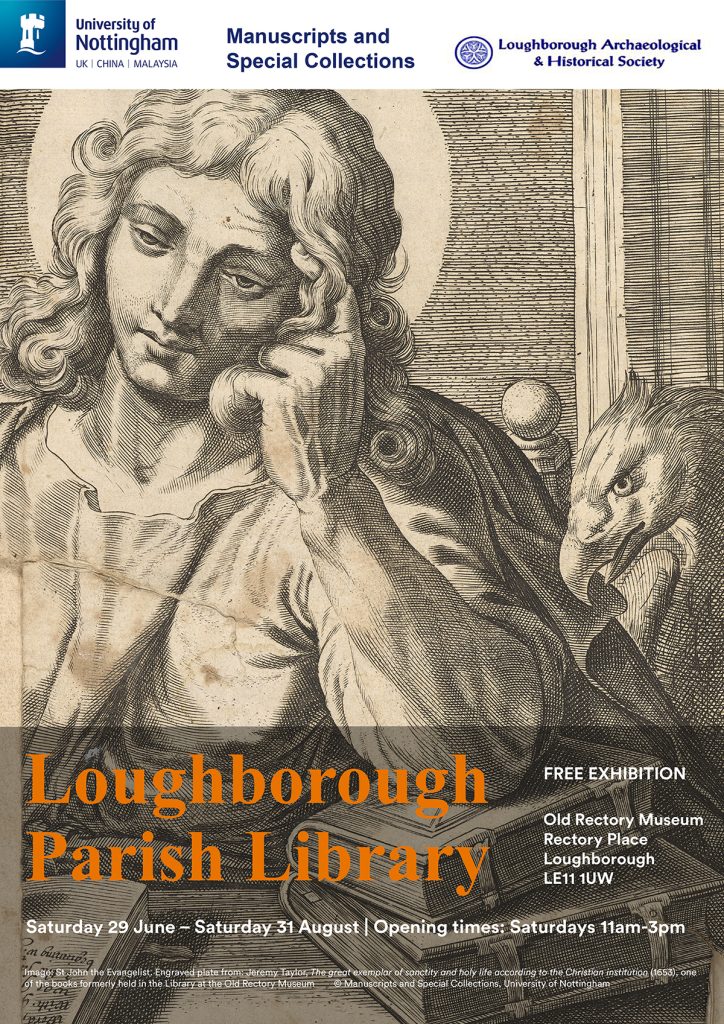

Loughborough Parish Library Exhibition – Old Rectory, Loughborough

3 August 2024

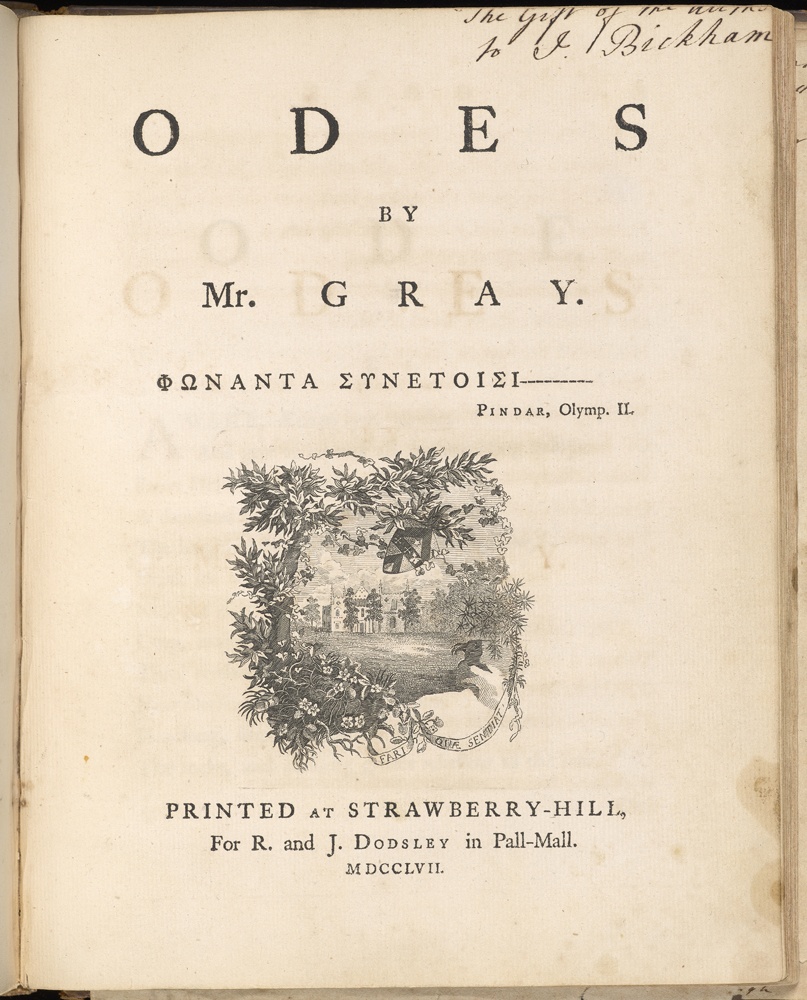

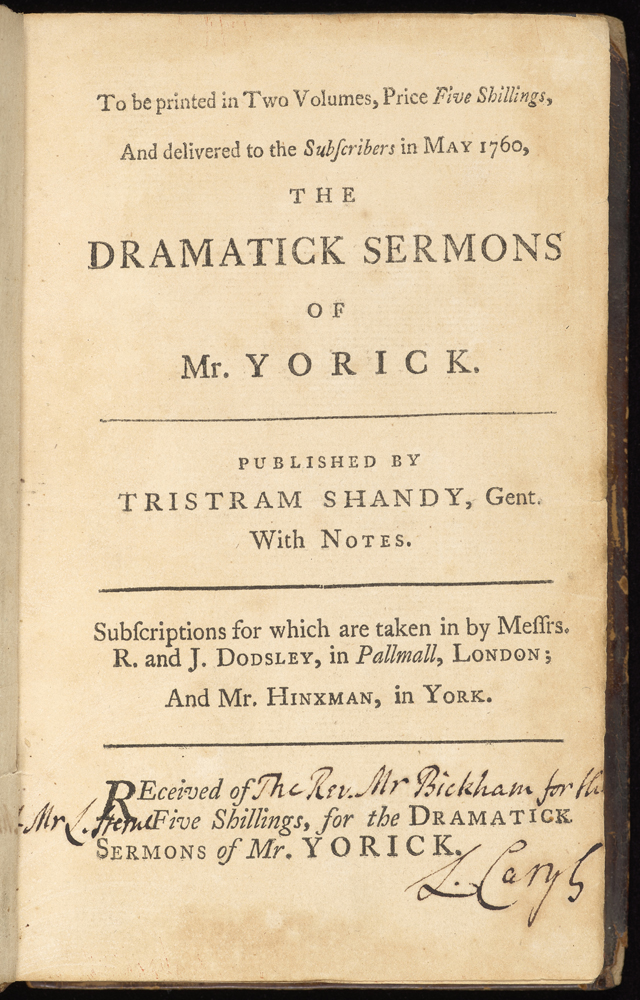

The Old Rectory Museum – former rectory for the Parish of Loughborough and once home to Rev. James Bickham and his Library of 700 books – is staging an exhibition this summer which sees reproductions of pages from some of those books on display in the town for the first time in many a year.

The exhibition is curated by Ursula Ackrill, the academic librarian responsible for cataloguing Bickham’s Library for University of Nottingham’s Manuscripts and Special Collections, where it is now housed.

Though some of the books from the original collection have been lost, the exhibition showcases items from the remaining 540 volumes, supporting a modern understanding of the importance of those works with information about the literary, religious and scientific developments being shared in them at the time Bickham was rector. Also on display are historical artefacts which a clergyman of some standing of that period would have been familiar with day-to-day.

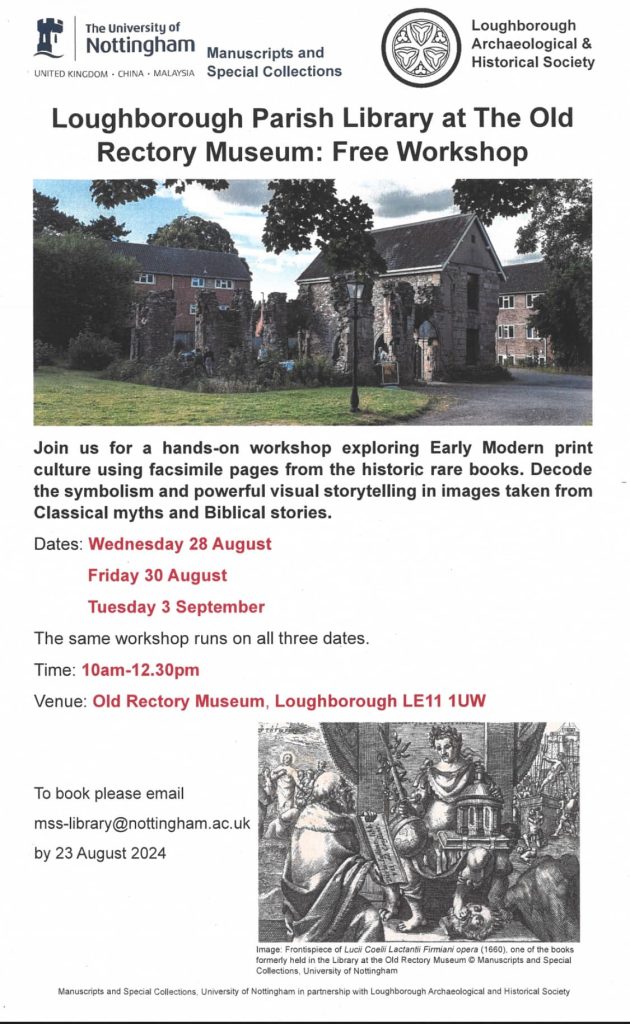

Alongside the exhibition itself, the Museum is staging a number of free creative workshops exploring early modern print culture and the symbolism of the classical imagery used in many of Bickham’s now rare collection of books.

The Loughborough Parish Library Exhibition runs on Saturdays at the Old Rectory Museum in Rectory Place until 31st August 2024. Details of this and the free creative workshops can be found below.

Article compiled by Alison Mott with information sourced from the Lynne About Loughborough website and the Loughborough Archaeological and Historical Society (LAHS) Facebook Group.

Loughborough Parish Library (5): A What-if Story from Loughborough’s Old Rectory

3 August 2024

In this article, Ursula Ackrill discusses the book-collecting habits of the clergyman who became Rector of Loughborough Parish on the death of James Bickham, and the ‘degrees of separation’ which link that clergyman to one of the most famous literary figures of all time.

The Reverend Samuel Blackall (1737-1792) succeeded to the rectory of Loughborough in 1786. Upon arrival in his new home, he found a collection of books waiting for him which his predecessor – the Reverend James Bickham – had bequeathed in his will to his successors in perpetuity: 700 volumes overall. A fine collection, which Blackall may have appreciated more had he not brought with him a library of his own. He was 49, unmarried, fond of the families of his siblings. In his will he left his own library to his two favourite nephews, Samuel Blackall, a clergyman, and John Blackall, a medic.

Blackall managed to keep his books separate from the Parish Library so that they could stay in his family. However, at least three books from Blackall’s library were left behind after his death. They are in the current Loughborough Parish Library, which is deposited in Manuscripts and Special Collections at the University of Nottingham.

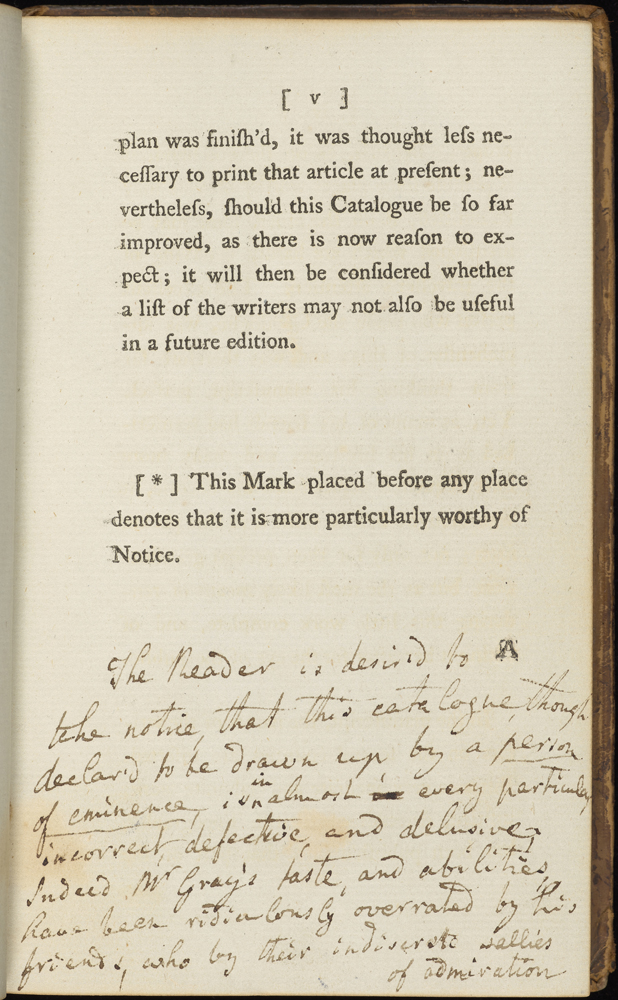

Blackall’s marginalia[1] show tantalising glints of his personality. In one instance, he could not resist puncturing what he perceived as a ‘cult of personality’[2] surrounding the poet Thomas Gray, whom his predecessor James Bickham had befriended in college.

Samuel Blackall comments in A catalogue of the antiquities, houses, parks, plantations, scenes, and situations in England and Wales by Thomas Gray (1773). Loughborough Parish Library, DA620.G73

When Samuel Blackall died in 1792, his nephew and namesake Samuel was 21. He had graduated from Emmanuel College, Cambridge, in 1791 and would become a Fellow of that college in 1794. He remained in college for twenty years. Presumably some or all of the library which the uncle had kept in Loughborough moved into his rooms there.

Emmanuel was both the uncle’s and the nephew’s alma mater. This raises the question why the nephew did not succeed the uncle to the rectory of Loughborough, which was within the college’s gift to bestow. The timing would have been perfect.

We know from contemporary sources, among them a lady with whom Blackall was briefly acquainted and nearly engaged to in 1798, that he was waiting patiently for one of the richest livings in the country to become vacant. That parish was North Cadbury in Somersetshire. In 1798, the lady’s hopes were disappointed. Fellows of Colleges were forbidden to marry, and Blackall must have felt unable to pursue a relationship at that point, knowing that the prospect of North Cadbury becoming vacant was a distant one.

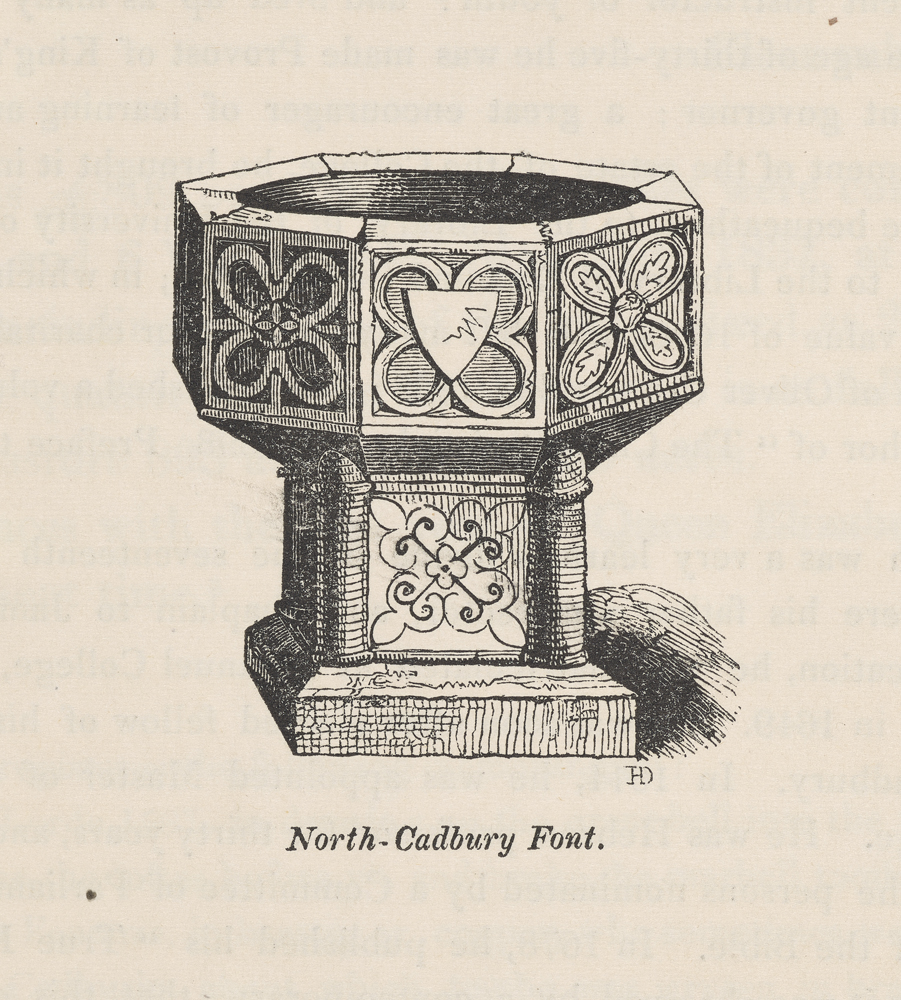

Samuel Blackall became Rector at St Michael, North Cadbury, in 1812, when he was 42. In January 1813, newspapers printed the announcement of Samuel Blackall’s marriage to “Susanna Lewis, eldest daughter of James Lewis Esq. of Clifton, late of Jamaica”. The bride was the Jamaican-born daughter of a prosperous owner of a slave-run sugar plantation. Her dowry explains the speed with which the couple managed to build their new home. It was completed in one year and looked interesting enough for William Phelps to comment on it in Antiquities of Somersetshire. Phelps wrote in the tradition of the great historians and aesthetes of English country style, Robert Thoroton, John Throsby and John Nichols.

“The rectory house is a neat building, standing in a spacious lawn near the church, and was erected by the Rev. Samuel Blackall in 1813.”

This must also have been the next home of the library which Blackhall inherited from Loughborough. Just one year later, in 1814, the couple baptised their first-born, a daughter, and named her Elizabeth – possibly after a spirited heroine in an en vogue novel which had been published in 1813 called Pride and Prejudice. In any case, the family kept the name, as Elizabeth’s own first surviving child, a daughter, would be called Elizabeth also.

As an adult, the latter settled in Sudbury, Derbyshire, and died in 1892. It is possible, then, that books from Blackall the uncle’s Loughborough library survive somewhere in Derbyshire. Blackall’s rectory in North Cadbury no longer stands and our attempts to find an image of it proved fruitless. We have, however, an image of the baptismal font, in which Samuel Blackall’s daughter Elizabeth was baptised in 1814.

If Samuel Blackall had succeeded his uncle as rector of All Saints, Loughborough, the lady he met in 1789 may have been his bride and relocated to Loughborough’s Old Rectory. We know she felt jilted, because she wrote a letter to her brother which leaves us in no doubt about it.

“I wonder whether you happened to see Mr Blackall’s marriage in the Papers last Jan[uary]. We did. He was mar- ried at Clifton to a Miss Lewis, whose Father had been late of Antigua. I should very much like to know what sort of a woman she is. He was a piece of Perfection, noisy Perfection himself which I always recollect with regard. – We had noticed a few months before his suc-ceeding to a College Living, the very Living which we remembered his talking of & wishing for, an exceeding good one, Great Cadbury in So-mersetshire. –

I would wish Miss Lewis to be of a silent turn & rather ignorant, but naturally intelligent & wishing to learn; – fond of cold veal pies, green tea in the afternoon, & a green window blind at night.”

Can you guess who the lady was?

Find the answer here!

© Article written by Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

[1] Handwritten notes and comments made by the reader in the margins of a book.

[2] A cult of personality is the glorification of an individual through the public outpouring of flattery, praise and devotion by their supporters. A contemporary of literary giants Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope and Samuel Johnson, and close friend of the writer and politician Horace Walpole, the poet Thomas Gray (1716–1771) didn’t in fact write a great deal of poetry, publishing less than a thousand lines of verse in his lifetime. He was, however, a prolific letter writer in an age when the personal letter was a rising art form. His correspondence to friends covered a remarkably broad range of topics with a clarity and ease not seen in his poems, a lack for which he was criticised by his peers. (Sources: enotes.com and poetryfoundation.org).

Previous post: a battle of books in Rev. James Bickham’s library

See also: University of Nottingham’s Manuscripts and Special Collections digital gallery of 114 images from Loughborough Parish Library

Brush Works, Loughborough

12 March 2024

Recently a friend and colleague asked me to write about the Brush Works in Loughborough, established by Charles Francis Brush in 1880. (Note: the original name of the factory was Falcon Works).

Their question was mainly, ‘what did the company make?’

The quick and easy answer is ‘almost anything!’ The company slogan was – ‘Brush can build it!’

About 100 years ago they were making D.C. generators for the then private electricity companies in the U.K. During the late 1880’s, the Brush also got involved with the production of small steam locomotives.

Before World War 2, they were producing electric trams for Blackpool, Sheffield and Hull. During the same war, the tram shops were repurposed to manufacture de Havilland 335 aircraft for the R.A.F. and parts for Lancaster bombers.

Post war products include small electric run-about vehicles for engineering establishments and, in 1956, large Lungstrom steam turbines made their appearance (under license).

In the 1950-1960’s huge 33kv transformers and associated rotating machines, plus switchgear, were all in evidence. The modernization of British Railways brought much fresh work to Brush in the form of diesel electric locomotives, first in 1955 with the introduction of the Type 2 locos, secondly in 1962 with numerous Type 4 locos.

Complete diesel electric power stations for the Middle East were made possible when Brush was absorbed into the Hawker Siddeley Group of companies in 1968. Sadly, The Brush has been ‘sold on’ at least twice, and now only Brush Transformers exist in Loughborough.

The remaining site has been sold to a variety of local manufacturing companies.

David Taylor,

(Brush Craft Apprentice in 1958)

The School Bell

2 September 2023

Sitting in my fire place is a brass hand bell with a polished mahogany handle.

It originally belonged to the head teacher at St Peters Junior School on Storer Road in Loughborough. On the closure of that school the bell passed to St. Peters Sunday School, as they were using the same premises. The safe keeping of the bell was the responsibility of Mrs. E. Kynnersley, one of the principal Sunday school teachers.

The bell found its next home with Mrs. K’s son Fred, and ultimately, with Fred and my aunt Kath, when they were subsequently married. The bell moved to Melton Mowbray, Grimsby and Kings Lynn, before finishing up in Kenilworth when my uncle retied from the Westminster Bank.

Sadly, they both passed away and I was offered the bell as part of their estate. I am pleased to say that it now resides in my lounge and is still capable of making a very compelling sound.

During the Covid 19 epidemic, the population of our country were encouraged to go out into streets at certain times to clap and bang in support of the NHS. As you might expect, we took our brass bell into the front garden, and joined in with the entire road.

With a renewed purpose: the bell was sounding out, the bell was back in business!

David Taylor

Loughborough Parish Library (4): a battle of books in Rev. James Bickham’s library

4 August 2023

In the latest article about Rev. Bickham and his vast collection of books which became the Loughborough Parish Library, Ursula Ackrill discusses the influence of the Puritan Hastings family on worship and education in Leicestershire from the 1500s onwards, the 18th century debate over a curriculum of Latin and the Classics versus ‘new’ practical subjects such as science and mechanics, how that played out in our local Grammar Schools and how Bickham’s own book choices act as clues to where he himself stood on the matter.

Until November 1775, people attending church services at All Saints, Loughborough, could rest their eyes on mural artworks including painted coats of arms, Old Father Time and “the figures of Moses and Aaron supporting the two tables of the Ten Commandment”. Moses and Aaron stood near the door of the North wall of the chancel. The historian John Nichols notes they were “handsomely executed in water colours” (Nichols, page 899).

On the wall above the arched entrance leading from the nave into the chancel were the King’s arms, painted in 1650, in the reign of King William III. Lastly, beside the royal arms were the arms and crest of the earls of Huntingdon – perhaps from the time of the Reformation, when the third Earl of Huntingdon had been patron of the living, between 1575-1585 (Nichols, page 899). The patronage of a living, also called advowson, consisted in the power to appoint a clergyman as priest of a parish and thus to give him the “living”, meaning the right to live off income from the parish. As receiver of parish income a priest was, and sometime still is, called the “incumbent”.[i]

The third Earl, Henry Hastings (1535-1595) had advowson of several livings beside Loughborough. Being a puritan, he involved himself in the war of ideas in his time. He used this right strategically to make political appointments, by giving the living of St Helen’s at Ashby-de-la Zouch, for instance, to puritan intellectuals such as Anthony Gilby, one of the translators of the Geneva Bible, and to Arthur Hildersham, a radical inspirational preacher and author. Allied with likeminded people, the Earl was fighting to win the hearts and minds of a society reeling from the rupture with the Catholic Church.

It has been noted by historians that the Earl may have been campaigning for more than just ideas, maybe rivalling Elizabeth I for the crown. Certainly, his lineage placed him in a plausible place for succession. However, the Earl’s record of founding and funding institutions of learning, such as the Ashby Grammar School in 1567, and the library at St Martin’s Church, Leicester, by 1586,[ii] to name just two examples beside the political appointments of rectors to St Helen’s, show a dab hand at ensuring that his puritanical goals were realised in his charities. They consumed his energy and much of his income. It is no surprise that the third Earl parted with his right of advowson of Loughborough’s All Saints only under pressure from the Queen. Nichols notes:

“When Sir Walter Mildmay had founded Emmanuel College [Cambridge], in 1584, he requested the queen, to whom he was chancellor of the Exchequer, to endow it with some ecclesiastical presentment; and, at her request, the said earl, by deed, dated Jan. 19, 1584-5, settled upon the college the advowson of Loughborough, together with those of Aller and North Cadbury, co. Somerset.” (page 899)

There was a later last-ditch attempt by the fifth Earl of Huntingdon to take back this right in 1642. By then the fifth Earl was nearing the end of his life; he had one more year to live. He claimed the transfer of advowson to Emmanuel College by the third Earl to be invalid because the Earl had overreached his authority, lacking the power to sell or give the advowson of Loughborough from the manor in the first place (Baker, page 82). If by implication he, the claimant, should have been consulted, as descendants ought to be before big decisions are made, this is quite funny. The Bishop waved the fifth Earl’s claim away.

Whilst the Earls lost advowson of Loughborough to Emmanuel College, they held on to that of Ashby – among other, smaller livings. In Ashby, puritanism drove the parish priest’s work well into the 17th century. The Grammar School’s schoolmasters built on the links established by the third Earl with Emmanuel College, by endeavouring to prepare boys for acceptance at that college. Looking back, a nice circuit emerges between Ashby Grammar School sending boys to study at Emmanuel College and then benefiting reputationally from their success. Moreover, because the prospect of obtaining the living of a parish nearby would have felt tangible to Grammar School boys inclined to study Divinity at Emmanuel College, we note that the school threw its support behind several poor pupils of merit (Fox, pages 17-30). This created a thriving environment for the life of the mind:

- John Hall (1574-1656), son of one of the third Earl’s bailiffs, would go to Emmanuel and become a Bishop as well as a published author of literature.

- John Bainbridge (1582-1643) became a famous physician, and later a professor of astronomy at Oxford. Newly graduated from Emmanuel, he returned home for a few years, set up as a physician and kept a school, whilst continuing to study astronomy. Little is known about his father, Robert Bainbridge, however a Robert Bainbridge is mentioned in the Ashby-de-la-Zouch school accounts as being the rent collector for the school-land rents; he may have been John Bainbridge’s grandfather (Fox, pages 132ff.).

- William Lilly (1602-1681), the son of a yeoman farmer, made his name as the master astrologer who predicted the execution of King Charles I. Lilly is now appreciated even more for his autobiography in which he memorialised his Grammar School days in Ashby.

The legacy of Puritanism chimed with the Grammar School curriculum. Essentially, the study of Latin and Greek was pursued to reconnect with the origins of the gospels, and so to recover the authenticity which the Apostles had lived in the beginning of Christianity – before the centuries of Catholicism when only clergy and educated, wealthy people could read the (Latin) Bible. On a practical note, Latin was Europe’s standard language in which all documents of consequence, from legal papers to dissertations, were written. It was the touchstone of the professions.

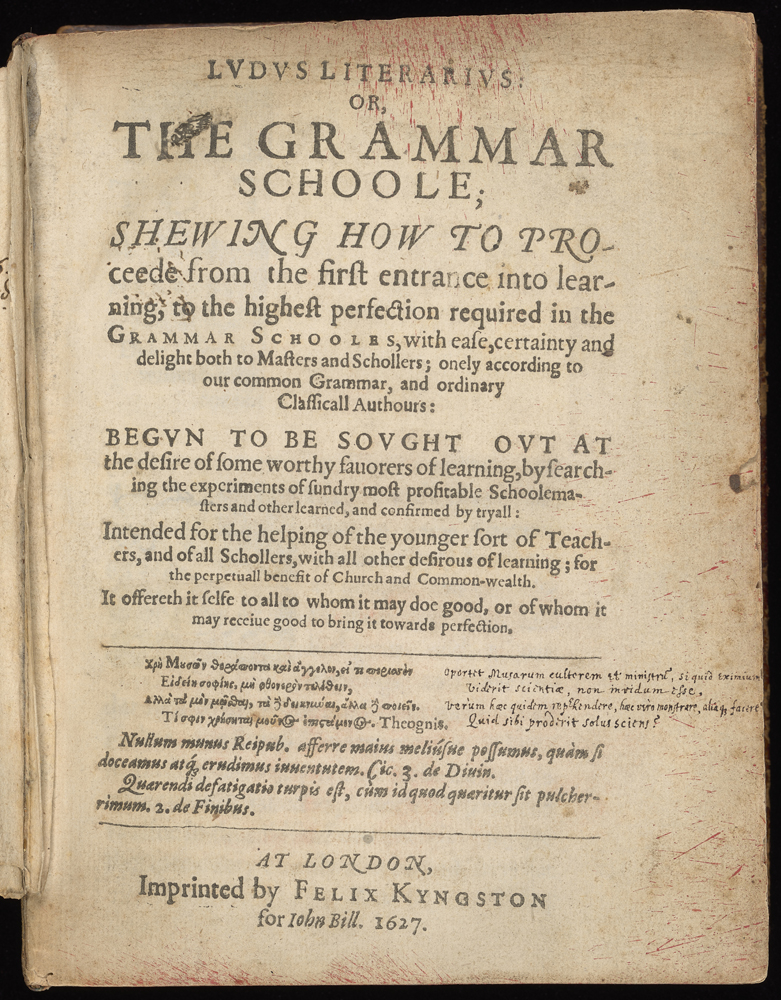

In the 17th century Ashby Grammar School had, moreover, the good fortune to appoint John Brinsley (fl. 1581–1624) as schoolmaster, who turned out to be one of the nation’s best educationalists. James Bickham owned a first edition of his 1627 work Ludus Literarius, and from the state of it we can tell that it has been well-used. Brinsley’s teaching popularised an intuitive learning method, using fun, games and schoolboys’ conversation, but implying that knowing Latin was fundamental. Brinsley may be the reason why Latin was taught in schools long after it stopped being needed.

In 1650 English replaced Latin as the official language in Britain, during the Protectorate, by a statute of 22 November 1650. However, as the Loughborough Parish Library shows, that did not mark the end of Latin, by far. 114 books in Latin survive in the LPL, but, of these, more than half (77) were published in the 18th century. In 1660, exactly ten years after English officially replaced Latin, the Royal Society was founded in London, setting standards for the pursuit of science nationwide.

The LPL shows high receptiveness towards scientific knowledge. Among the Rev. Bickham’s science books we find Isaac Newton’s new books on optics and mechanics; books with plates showing how to plot the orbit of planets and satellites; books about the use of globes for navigation; and a medicine book with anatomical illustrations. Of course, those books came with the territory when the territory was Cambridge or Oxford or London. Everywhere else in 18th century rural England, confidence in Grammar School education was at a low ebb.

During Rev. Bickham’s time as Rector, Loughborough Grammar School was stuck in a deep crisis. From its beginning the School had measured success by the number of its pupils accepted to study at Cambridge: that number sank drastically in the 18th century. To make matters worse, a schoolmaster who had been in post for 25 years neglected his work up to the point that his pupils charged him with dereliction of duty in front of the town estate (23 November 1770; White, page 129). Bafflingly, he managed to stay in post for another three years after that. Why was education in the 18th century so heavy-footed in the face of change? Why were schoolboys still “making Latins” instead of learning maths and geography?

In All Saints Church the Huntingdon arms were whitewashed over forever in 1775. Nichols writes:

“Nov. 4 1775, the king’s arms were fresh painted and finished for the church by Bagnall; at which time Moses and Aaron were washed out, as well as Time and the Huntingdon arms, by order of Mr. Archdeacon Bickham; the church new white-washed; and the Lord’s Prayer, the Creed, and Ten Commandments written in gold letters on the altar.” (Nichols, page 899).

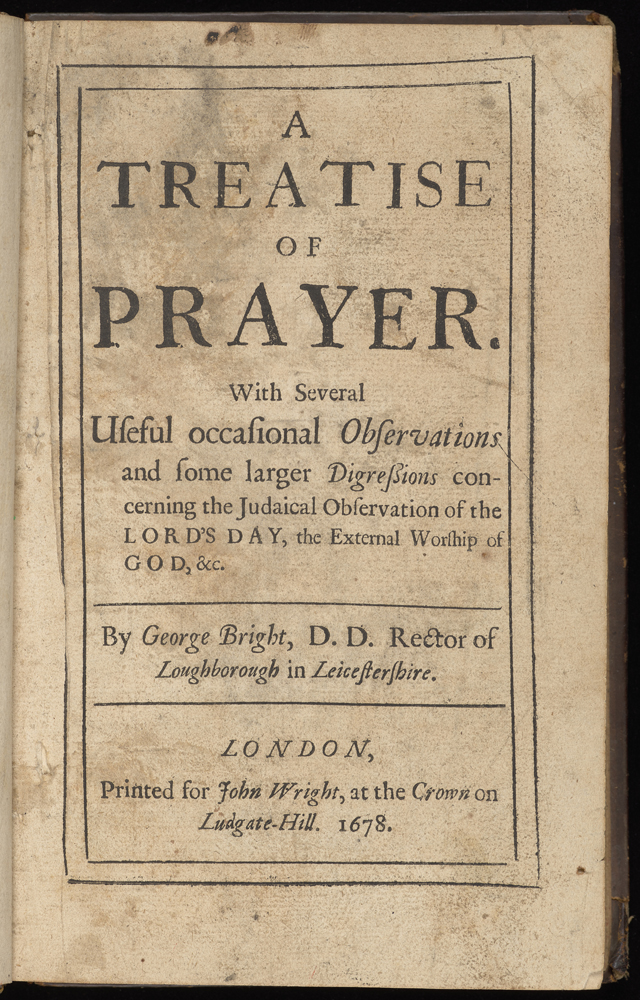

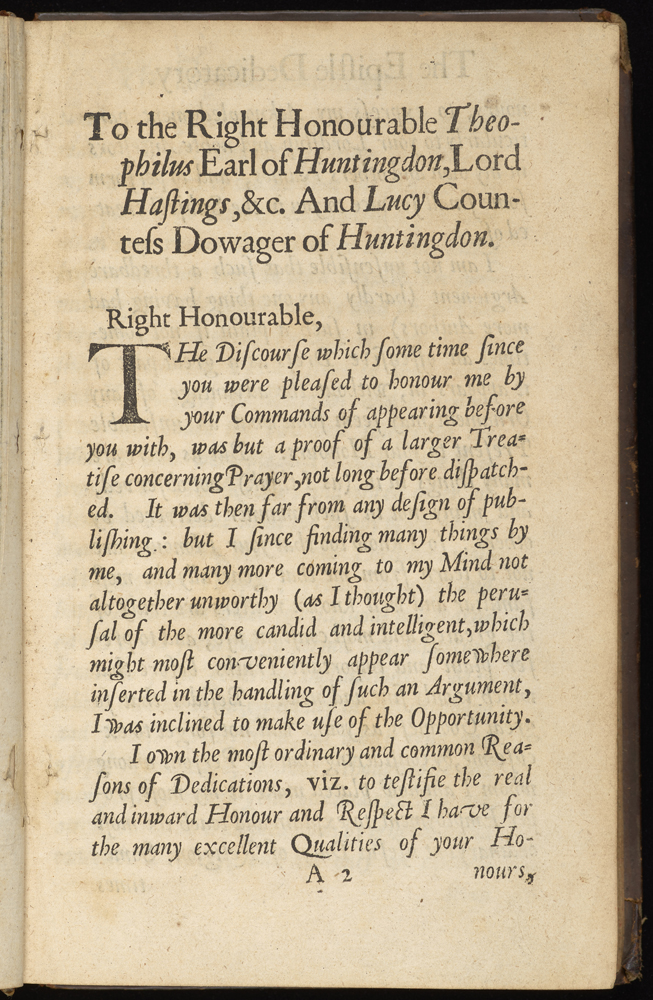

In his capacity as Archdeacon of Leicestershire, James Bickham ordered whitewashing, among all sorts of repairs and purchases, for more than half of a total of 240 Leicestershire churches during official visitations he undertook between 1773 and 1779 (Pemberton, page 56). It should come as no surprise that the Huntingdon arms were deleted from the wall in All Saints: unlike the royal arms, they were not officially prescribed. Besides, the Hastings family’s leadership was by then confined to local history. Even a century earlier, when George Bright, Rector at All Saints between 1669-1696, dedicated his 1678 book A Treatise of Prayer to the seventh Earl of Huntingdon and his mother, the Countess Dowager[iii], one cannot escape the impression that Bright’s dedication already courted the Earl and the Countess just for their cultural status as fellow-intellectuals, whilst little remained of the feudal power they had wielded in the 1500s.

However, the black maunch in the Huntingdon coat of arms has a haunting resemblance to the article of clothing which Bickham ordered – obsessively, it seems, – in his visitation records to be worn by priests. That article of clothing is a “black silk hood”, to be worn by the priest officiating service: there are 135 such items ordered. We have to ask, what accounts for the great number of mentions of “black silk hood” in relation to the overall number of vicars serving God in Leicestershire? This hood must have been important to Bickham! Why? Wearing a black silk hood over the surplice signified that the priest was a graduate of a university. At a time when school learning was in deep crisis, Bickham was signalling that degrees were valuable and conferred authority. Priests should be proud to hold a degree and wear the hood at holy services.

Kitting out priests with black silk hoods might seem like a rather quaint or hopeless gesture when we look at the hold which the old ways, symbolised by the maunch in the Huntingdon coat of arms, still had over a society beginning to modernise. The Reformation had not just enshrined the study of the classics in schoolrooms and turned religion into an open door to the past, where every Protestant could encounter Christ as directly as His disciples did in Galilee, A.D. The books collected by our Rev. Bickham in his library show us that classical antiquity, the Greco-Roman stories, had crept into popular imagination.

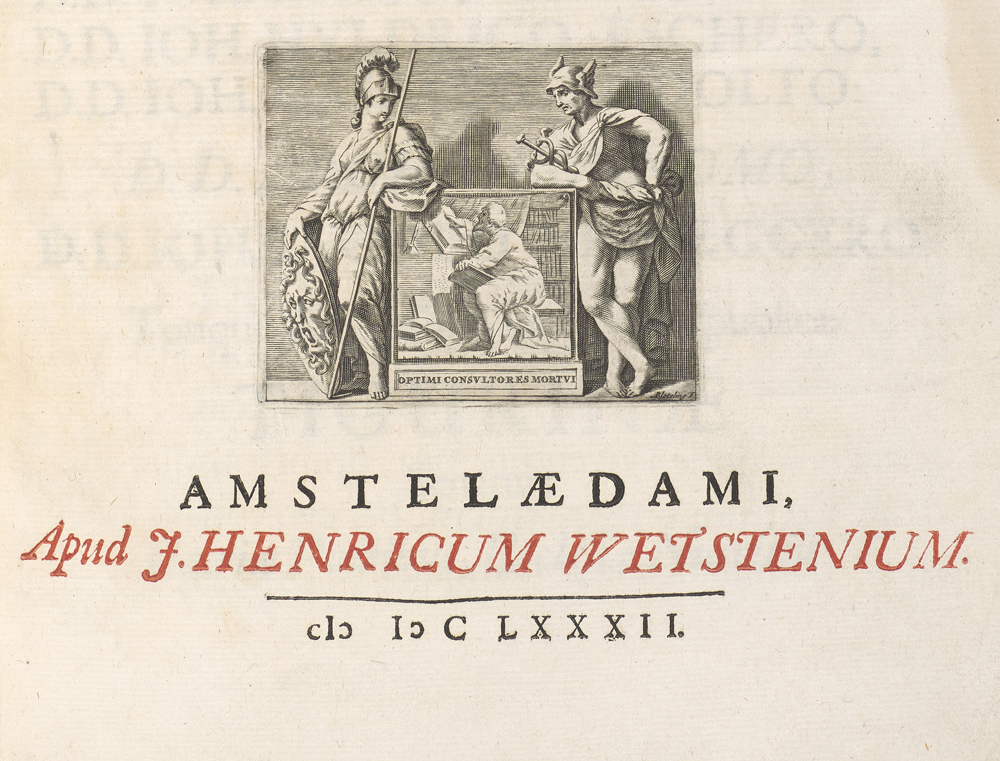

Publishers from London and cities across continental Europe published Latin as well as modern language books and sold them across national borders, as evidenced by the fact they were gathered in collections like Rev. Bickham’s. These publishers designed brand signs, the so-called printer’s device, which were engraved on every title page’s lower bottom half, with figures from the classical ancient world. The ancients were aspirational glamour figures, used to signify quality and guarantee value for money.

Writing of the mentality of medieval western Europe, Simon Winder notes that: “Humans were doubly fallen though – not just expelled from Eden, but also expelled from the classical ancient world. The medieval rulers of Western Europe were obsessed by a sense that they too were the mere followers of ancient greatness. Their battle tents and palaces were festooned with huge tapestry images of Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great.” (Winder, page 33)

What we notice looking through the books of Rev. Bickham is that by the 18th century the ancients were popular culture, referenced to enhance prestige as readily as today’s celebrities are in product endorsement. And yet, at some point in becoming a modern capitalist society in the 18th century, the reflex to look back across millennia for truth and authenticity, to the beginning of our Judeo-Christian and Greco-Roman history, was replaced with the belief that humanity has what it takes to progress to better things – in future. That our golden age was yet to come.

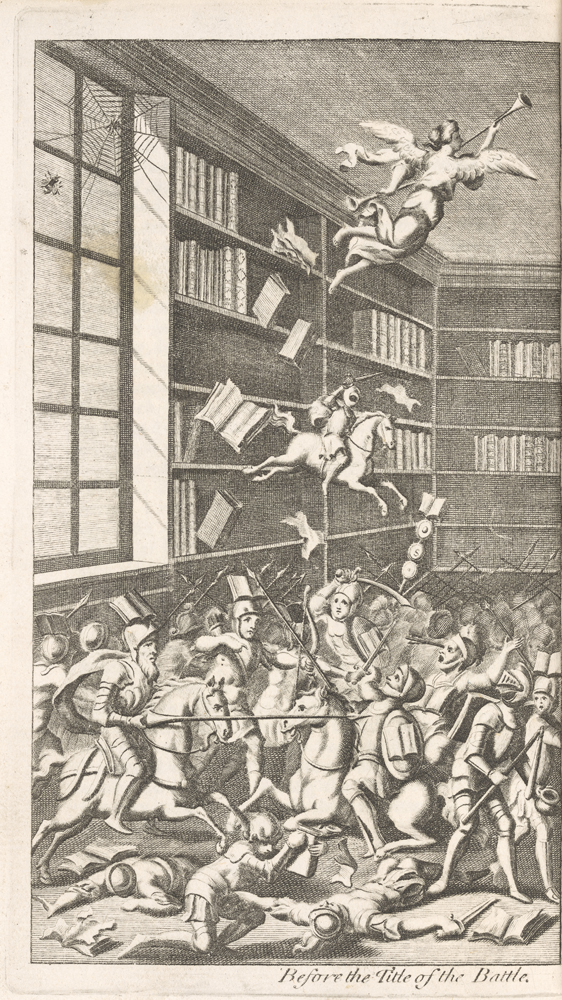

A curious little story in Rev. Bickham’s library tells us more about the missing step between the two mindsets. It was written in 1704 by Johnathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels. Swift’s politics were Tory, but it is simplistic to expect his sympathies in An account of a Battel between the Ancient and Modern books in St James’s Library to be with the Ancient books. The story introduces the concept of the original thinking mind, which has enough native ingenuity and talent to originate inventions that improve and ultimately outdo legacy practices.

The originator of inventions is voiced in this story by the spider, whose net is torn by a roaming bee. Their confrontation takes place by a window of St James’s Library where the books face each other in battle: the Ancients being authors from antiquity and their contemporary champions, the Moderns on the other hand being a motley crew of critics – because change requires critique – and assorted contemporary innovators, especially in the fields of mathematics and architecture. In those disciplines the Moderns felt they had the advantage over the Ancients.

Whilst the Battle carries on, the spider and the bee engage in their debate. Swift seems to be on the side of the bee, however the spider has arguably the sharper-written lines. The spider disses the bee for being “but a Vagabond without House and Home, without Stock or Inheritance […] born to no possession of your own […]. Your livelihood is a universal Plunder upon nature; a Freebooter over Fields and Gardens;” (Swift, page 170). His accusation against culture derived from widespread sources recalls a more recent incarnation of this idea, expressed by Teresa May at the Tory Party Conference 2016: “If You Believe You are a Citizen of the World, You are a Citizen of Nowhere.”

As for himself, the spider says: “I am a domestic Animal, furnish’d with a native Stock within myself. This large Castle (to shew my Improvements in the Mathematicks) is all built with my own Hands, and the Materials extracted altogether out of my own Person.” (Swift, page 170) However, the large castle is in fact a spider’s net which the bee tore to pieces without even meaning to. Swift thus makes the argument that the inventions of the Moderns cannot last. In this staged debate Swift allows the bee to win. History was on the side of the spider, as Swift surely knew. It was the spider’s confidence in his own genius that was lacking in Bickham’s contemporaries who failed so miserably to rethink education.

Better schools were not unheard of, but without a national overhaul they could not prevail. A private school, the Loughborough Academy, sprang up in competition with the old Grammar School in 1793, opening in a house on Derby Road. It taught the old Grammar School subjects of Latin, Greek and grammar alongside “French, Italian, writing, arithmetic, astronomy, geometry, navigation, merchants’ accounts, mensuration (ie measurement) of superficies and solids, surveying, gauging, mapping, architecture, geography, use of globes, projection of the sphere, drawing, dancing and fencing.” (White, 130) Had Bickham still lived, he would have approved.

© Article written by Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

Resources:

John Nichols, The history and antiquities of the county of Leicester : Compiled from the best and most antient historians, Volume III, Part II (1795-1815)

Thomas North, The Accounts of the Churchwardens of St Martin’s Leicester, 1489-1844 (1844)

M. Claire Cross, The Third Earl of Huntingdon and Elizabethan Leicestershire, in Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol. 36 (1960)

Margaret Baker, The life and times of the Rectors of Loughborough (2012)

Levi Fox, A Country Grammar School (1967)

Alfred White, A history of Loughborough endowed schools (1969)

Visitation by Archdeacon James Bickham, 1775-1779, pp. 1-296. In Leicestershire Record Office, Document Reference 1D41/18/21

W.A. Pemberton, The parochial visitation of James Bickham D.D. Archdeacon of Leicester in the years 1773 to 1779, in Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol. 59 (1984-85)

Simon Winder, Lotharingia : a personal history of France, Germany and the countries in between (2019)

Jonathan Swift, A tale of a tub : Written for the universal improvement of mankind. To which is added, an account of a battle between the ancient and modern books in St. James’s Library. The 10th edition. (1743)

[i] Back then the parish priest’s income came directly from nearby land: glebe income and tithes. Glebe is an area of land within a parish used to support a parish priest. A tithe is the tenth part, the amount each parishioner had to contribute from their own income for the maintenance of the priest. Tithe payments hark back to early Christianity, adapted from the Old Testament: Every tithe of the land, whether of the seed of the land or of the fruit of the trees, is the Lord’s; it is holy to the Lord. (Leviticus 27:30-34).

[ii] The library commissioned by the third Earl formed the nucleus for the Leicester town library, which moved to the Town Hall in 1635, according to M. Claire Cross (Cross, page 15 and North, page 132). The surviving St Martin’s books are now kept in display cabinets in the Guildhall.

[iii] Lucy Davies Hastings, Countess Huntingdon, wrote poetry, or has poetry attributed to her as she never published it; her writings are kept in the University of Edinburgh (MS Laing III. 444).

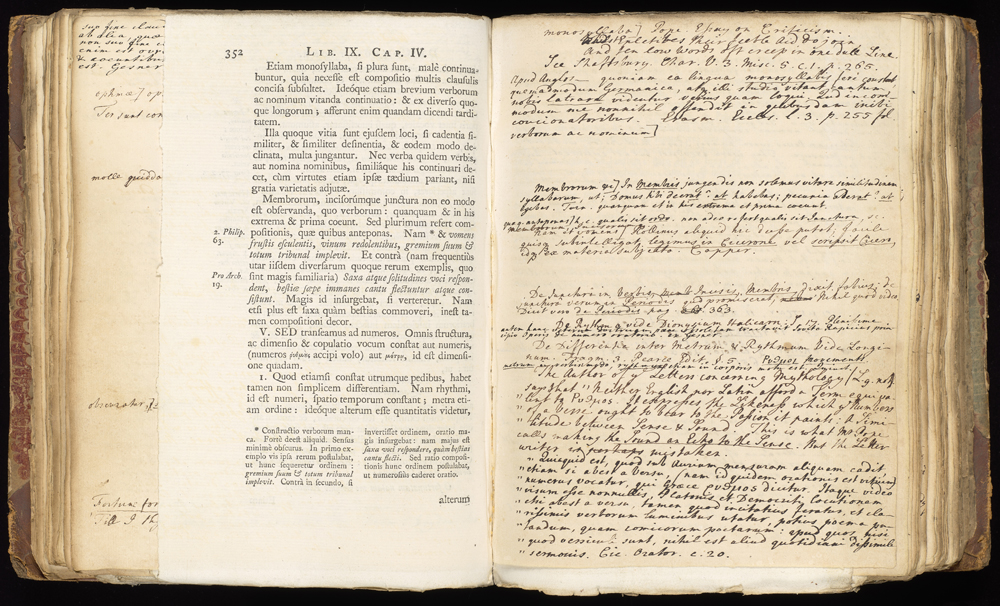

M. Fabii Quintiliani Institutionum oratoriarum. Volume 2. Loughborough Parish Library, PA6649.A2 .D38, barcode: 1008347058

Previous post: Loughborough Parish Library (3): curator James Bickham (1719-1785)

Next post: Loughborough Parish Library (5): A What-if story from Loughborough’s Old Rectory

Rectors and Vicars explained

30 June 2023

So, what exactly is a rector?

A rector in the Church of England was (and continues to be in parishes such as Loughborough) essentially a parish priest, with the same duties as those carried out by a vicar, a role we’re perhaps more familiar with today.

Historically, those duties have included –

- leading morning and evening prayers;

- delivering sermons in the regular round of church services and

- additional sermons on saints days and holy days;

- officiating at christenings, marriages and funerals;

- attending meetings to deal with parish matters, and

- supporting the needs of parishioners in the community, including the poor.

The difference between the post of rector and vicar comes down to status, with a rector considered of higher social standing than a vicar and the income – or stipend – he received reflecting that difference.

Parishioners covered the cost of their parish priest through payment of a tax – known as a tithe – on the crops they grew, the animals they raised and the goods that they made.

The word ‘tithe’ – from the Old English word teopa – means ‘one tenth’, and this was the percentage each parishioner must hand over to their local representative of the Church of England from everything they produced. Tithes were a legally enforceable tax and all parishioners had to pay them, whether they followed the protestant faith or not.

The wealthier those parishioners were, then, the greater the amount of goods their parish priest received, and the wealthier he himself became as a result. The broad, flood-enriched meadows of Loughborough parish easily sustained flocks of sheep whose wool was turned into cloth and sold as far afield as Calais. Because of this, local landowners became very rich and in turn, so did the local Rector. As mentioned elsewhere, the ‘living’ of Loughborough was indeed a very handsome one.

Initially, tithes were collected largely as goods, a one-tenth portion of the annual harvest and stored by the priest in tithe barns built for the purpose.[1]

It’s been said the idea behind paying the clergy like this was to link the fortune of a cleric with those of his parishioners, so that all did well when the harvest was a good one and suffered equally when it was bad. Whether this was originally the intended purpose or not, cases of clergymen struggling to get people to hand over their tithes are well documented (including for Revd Bickham).

To complicate matters, there were two levels of tithes –

- greater tithes, which included everything that arose from the ground – wheat, oats and barley, for example, as well as hay and wood, with even windfall apples being taxable[2], and

- lesser tithes, which were all things nourished by the ground – the produce of livestock such as eggs, milk and butter – and the livestock itself – chickens, lambs, pork and the like.

As you might guess, the higher-statused rector was entitled to receive tithes from both categories – the greater and the lesser, whilst a vicar only received the lesser tithes – about a quarter of all the tithes collected in the parish.

This didn’t mean that a parish with a vicar got off lightly, however. The full ten percent tithe was still collected in, but with the remaining three-quarters being paid to whoever owned the advowson for the parish (which as stated previously, might be the lord of the manor, a wealthy private individual or an institution such as a university). Another very good reason for buying up an advowson if you were able to.

So, as a result of the difference in the tithes they were entitled to receive, clergymen with the title of rector tended to be wealthier (and by association, more powerful) than those who were merely vicars.

Interestingly, these differences are reflected in the titles themselves. The word rector is related to the words right and rectify, signifying that the role of the rector was to lead his parish in the right direction.

The word vicar comes from ‘vicarious’ – from the Latin noun vicis, meaning ‘stead’. The oldest meaning of vicarious, dating to the first half of the 1600s, is ‘serving instead of someone or something else’.

Rectors had an additional advantage over vicars in that parishes headed by a rector usually had farm land – known as glebe land – designated for the cleric’s use and thereby providing additional income from crops and livestock, or from rent.[3] In return, the rector was responsible for paying for any repairs that were carried out to the chancel[4] in the church, an obligation not expected of a vicar.

Well-paid rectors and vicars had enough disposable income to employ a lower-ranked clergyman to carry out much of the day-to-day work of the parish on their behalf. These were known as a curate, a word meaning to be responsible for the ‘care or cure of souls.’ Technically, then, any clergyman could be classed as a curate, though in reality the expectations on the roles were very different.

Alison Mott

[1] This was changed to a monetary payment of their value in the Tithe Act of 1836.

[2] From ‘Tithes and the Rural Clergyman in Jane Austen’s England’ by Eileen Sutherland, on the website of the Journal of the Jane Austen Society of North America, sutherland.pdf (jasna.org) [accessed 23.6.23].

[3] From the Latin gleba or glaeba, meaning clod, land, soil

[4] The area behind the altar.

Bickham bides his time

23 June 2023

Before James Bickham came to Loughborough to take up post as Rector of the parish, he’d been waiting for a living for some time, ‘kicking his heels’ for 20-odd years as a Fellow at Emmanual College, Cambridge, a two-hundred-year-old university established specifically to educate Protestant preachers.[1]

As noted in the previous blog, a career in the Church of England had historically been considered a desirable option for a young man with limited funding but a decent level of education. The Church was (and continues to be) a hierarchical institution much like any other, made up of various levels of personnel, each receiving a salary in proportion to rank and status.

The post of Fellow at Emmanual College largely involved the teaching of undergraduate students – all male at that time, and all destined for the Church – along with some administrative and governance duties. It wouldn’t have been a highly paid post, though Bickham is likely to have ‘lived in’ alongside the students and therefore had his food and accommodation costs covered.

More interesting to modern-day readers, perhaps, is that during this era Fellows weren’t allowed to marry, and for Bickham to have waited for a parish for so long, deferring marriage to his long-term sweetheart in the process, he must have been confident that the living of Loughborough would one day be his. Or perhaps, as Ursula Ackrill has surmised, it’s simply that Bickham enjoyed the protected, scholarly life at Cambridge so much he was reluctant to quit it for a post in a parish, with the routine and hard work, difficulties, politics and intrigues to be navigated and overcome that went with it.

There was no retirement programme for clergy back then, particularly for those without an independent income to retire on, and clergymen generally remained in post until they died, no matter how old or ill they became, their duties carried out by a subordinate if they were too unfit to fulfil them themselves.

Bickham’s predecessor, the Revd Thomas Alleyne, whom he may possibly have met on his visit to the town in 1758, was only in his fifties but had been ‘afflicted with the gout’ for many years. He died in Bath in July 1761, leaving the way clear for Bickham to have the parish.[2]

It seems likely James Bickham will have been promised the living at Loughborough by someone influential at Cambridge, though it’s not known, now, who that might have been and why they favoured Bickham.

Whatever the circumstances of how and why he acquired it, with a stipend of more than £400 per annum – equivalent to almost £110,000 a year today – it would definitely have been worth the wait. [3]

(Image in ‘Caricature History of the Georges’, Pub. Chatto and Windus, Piccadilly, 1876.)

Alison Mott

[1] From ‘History of the College’ on website of Emmanuel College, [accessed 23.6.23]

[2] ‘The Rectors of Loughborough’ (1882) by William George Dimock Fletcher, on Google Books website Google Books website. Gout is the acute onset of inflammatory arthritis caused by the buildup of uric acid in the blood. Untreated, it can lead to joint and bone damage, heart, lung and kidney disease and result in premature death. Ref. Healthline website.

[3] See CPI inflation calculator here.

See previous post here.

The ‘Church Living’

16 June 2023

Revd James Bickham arrived in Loughborough in 1761 to take up the ‘living’ as rector of the parish and incumbent[1] of the church of St Peter and St Paul (now known as All Saints with Holy Trinity) – one of the major churches in Leicestershire.

Throughout time, to be a clergyman in the Church of England has meant to hold a respectable and influential position within an establishment at the heart of the governance of the country.

Historically for many in the clergy, the post came with free accommodation – a house to live in and raise a family – along with a secure stipend, or salary, to feed and clothe them with, both a very desirable thing in a time when there was no expectation on the state to house the homeless or top-up lack of income with benefits of any kind.

Added to that, the work of a cleric wasn’t the physical, manual work those at the lower end of the wealth scale were mostly required to do in order to earn a living. To be a clergyman required a certain skill-set, certainly – a particular level of education, for instance, at a time when schooling was neither free nor available to everyone, and at minimum an outward appearance of complying to the principles of the Christian religion as laid out in the Bible. But for the most part, ‘work’ as a clergyman offered a settled, sedentary and routine existence, with opportunities for socialising, reading and reflection and – at the higher levels particularly – a comfortable day-to-day life.

The role came with many benefits such as status within the community, and the opportunity for progression through the ranks for those with the right skills and attitude – and, most importantly, connections – to take them. A job worthy of an educated gentleman, therefore, traditionally seen as suitable for the second sons of titled or wealthy families who, because of primogeniture[2], had little or no inherited money of their own to live on. As such, a ‘church living’ was looked on in practical terms, sought more as a way to secure a life-long income than as a ‘calling’ to share the word of God (though there were undoubtedly clergymen who would have had this calling, too).

Church livings were handed out through patronage, or the support of someone with wealth and influence, who often owned the right to decide on the postholder for a parish. These rights – known as advowson – often belonged to titled families and wealthy landowners, to Bishops within the Church of England and even to prestigious universities. In Reverend Bickham’s day it was possible to sell an advowson to others, and common for them to be bought and held ready for a friend or relative to take up when they were old enough or the current post holder moved on.

And as the Church was a hierarchical institution, there were different levels of livings within it to be bought, sold and granted by patronage to an educated gentleman in need of an job. So, back we go to the question of Revd Bickham and what brought him to Loughborough to be rector.

(Continued here)

Alison Mott

[1] A term meaning the holder of a post or office.

[2] Primogeniture is the custom of passing a deceased person’s entire wealth to their firstborn legitimate child (generally males) rather than sharing it out amongst all their children.

Loughborough Parish Library (3): curator James Bickham (1719-1785)

2 June 2023

His library tells us that the Rector James Bickham earned his learning through hard work.

We know he loved books: he bequeathed his library to his successors and left specific books as a gift to a friend in his last will and testament. Bickham also continued to acquire new publications until the end of his life. In 1785 he added two new books, a presentation copy of discourses by Thomas Balguy, Archdeacon of Winchester, and a volume of poems by Milton, both ©1785.

However, we see conclusive evidence that Bickham worked hard at his studies when we examine three books that have survived in the library. They are a Greek Grammar, a Latin book on public speaking by the Roman author Quintilian, and a modern treatise on law.

From the date of their publication, it can be assumed that Bickham used them as an undergraduate at Emmanuel College. The leaves of printed text are interleaved with blank leaves, a popular fashion of binding for people who used texts for study. In Bickham’s three college textbooks the blank leaves are covered with handwritten practice tracts of translation, vocabulary, commentary, and copied-out phrases.

We know that after graduating in 1740, Bickham became a Fellow of Emmanuel College from 1743-1761. He obtained this job thanks to his hard-earned erudition[1]. This Fellowship appears to have been his sole source of income.

We know that Bickham waited until he was aged 42 to marry the woman he loved. In 1761 Bickham arrived at Loughborough a bachelor, but was within three months married to Sarah Williams, his long-standing lady friend from Cambridge. Fellows were forbidden to marry, and it seems likely that Bickham could not afford to resign his Fellowship.

Emmanuel College had advowson – that is, the right to appoint members of the Anglican clergy for a vacant benefice[2]. However, this depended on a benefice becoming vacant upon the death or, more rarely, resignation of the incumbent[3]. It appears that Bickham had no other route, such as a wealthy patron or influential backer, beside the hope that college would provide him with a living.

However, it is also possible that he enjoyed the scholarly life in college and gave it up only for one of the richest benefices. Local historian Margaret Baker discovered in her research that in 1758, Bickham had been sent by his college to Loughborough to report on the effect the proposed Enclosure Act would have on the glebe lands of All Saints. In 1761 Bickham accepted Loughborough at the same time as the Enclosure Acts were passed.

Bickham’s old friends from Cambridge, who like him vied to secure positions in the Church (William Mason, poet and later canon of York Minster and Richard Hurd, author of essays and later bishop of Worcester) or struggled to remain employed in college (Thomas Gray, the poet best-known for Elegy in a Country Churchyard), gossiped specifically about the wealth of his benefice. Thomas Gray wrote to William Mason: “Jemmy Bickham is going off to a living, better than £400p.a., somewhere in the neighbourhood of Mr Hurd and his old flame, that he has nursed so many years, goes with him. I tell you this to make you pine.”

The reality of being a Rector at All Saints took Bickham away from reading his books. Margaret Baker suggests that because of Loughborough’s enclosure, people who fell on hard times did not pay their tithes[4]; consequently, Bickham filed in his first decade as Rector ten suits against parishioners, to collect his dues.

In the following decade Bickham undertook lengthy and expensive repairs to the Rectory, which he financed himself[5] as was his duty as Rector. As archdeacon of Leicester, Bickham completed visitations between 1773-1779 to all churches in his purview[6] and wrote detailed memoranda requesting improvements to the buildings, probably drawing on lessons learned from his restoration work in the Rectory, as well as calling to order slack and impious practices such as schooling children in the church, neglected vestments[7] and books.

His diligence and rigour in delivering his duties were noted by historians. Yet at the same time we note that he never published anything. In his last will and testament, Bickham specifically asked his executor to burn all his sermons, letters and papers. In fact, were it not for annotations left behind in books, we would have no personal statement from Bickham beside the instructions made during church visitations – and his testament.

Gray, Mason and Hurd left lasting bodies of published work behind. Bickham, however, did not. He was in awe of his writer friends, that much we can surmise. Remember the two volumes of Milton’s prose which he gifted to Hurd in his will? They are deluxe editions, worth considerably more than the four books Hurd gifted him, of which two were duplicates from Hartlebury Library, a library for which Hurd was custodian – not creator. Weeding [out] duplicates is a basic management measure in looking after library collections.

Hurd was Bickham’s junior by one year and both had matriculated as sizars at Emmanuel College. A sizar is, according to the glossary on the University of Cambridge’s website, “a student originally financing his studies by undertaking more or less menial tasks within his College and, as time went on, increasingly likely to receive small grants from the College”. Gray, on the other hand, had gone to Eton College before matriculating at Peterhouse, Cambridge, as a pensioner (meaning a fee-paying student).

As an undergraduate Bickham earned himself a reputation as a prize-fighter and it is tempting to imagine Gray “managing”, or rather running a book, on the talent of the slightly younger sizar. Bickham was a gifted linguist, not just writing freely in Latin, as we can glimpse from his marginalia, but collecting Don Quixote in both Spanish and Italian, alongside Italian editions of Tasso, and Machiavelli, to name just two of his favourite Italian authors. Yet we do not know whether he travelled abroad.

What is certain, is that Bickham would have seen his friend Gray depart in 1739 on his Grand Tour to Italy and France at the invitation of Horace Walpole, from Gray’s Eton circle of friends. With Horace Walpole, son of Prime Minister Robert Walpole, Gray spent two years abroad. It was not extravagant for middle-class clergymen like, for instance Lawrence Sterne, to embark on a Grand Tour. In Jonathan Swift, whose works Bickham collected avidly, and in Sterne, whose The Sermons of Mr. Yorick Bickham obtained by subscription, he beheld two leading lights of the literary world who had great careers in the Church just the same.

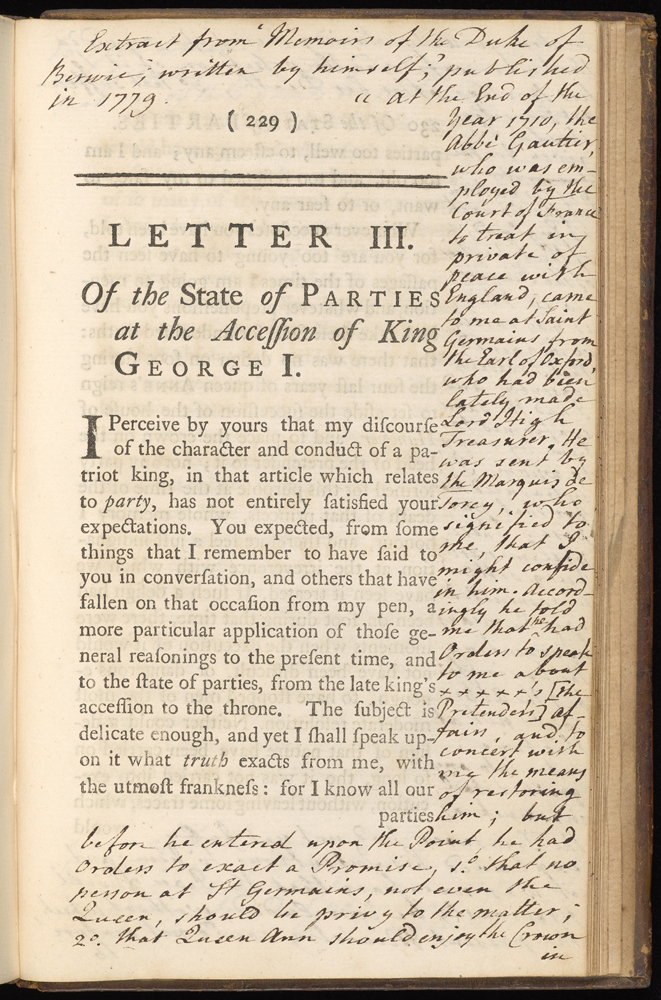

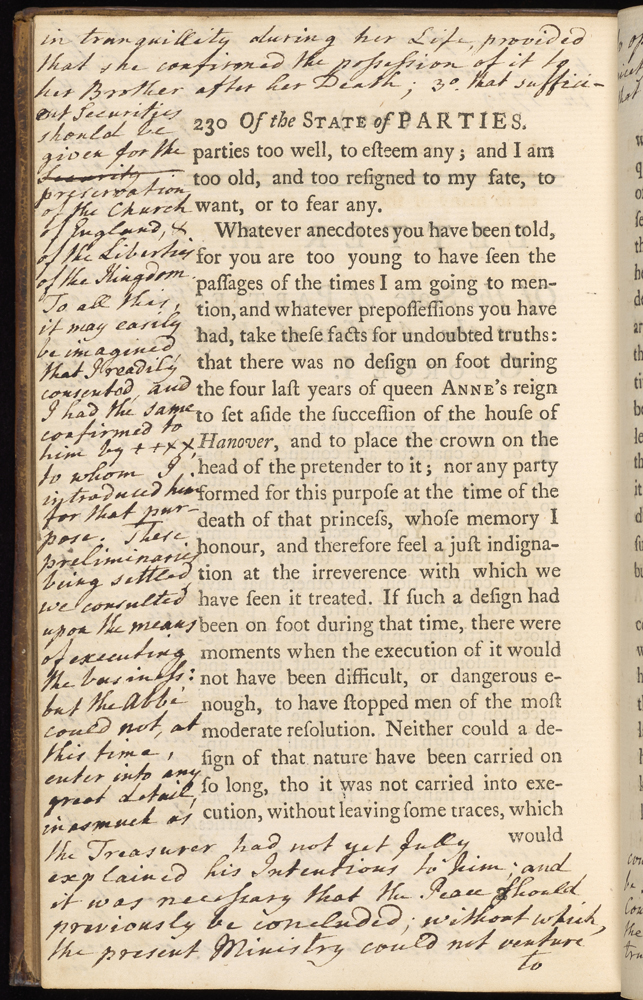

In the critical comments Bickham wrote in page margins and on blank leaves, he comes across as a frustrated critic, whose high standards are not being met by others. Further research is needed to confirm whether Bickham was being original, or whether he copied out paragraphs from other sources such as periodicals. Even if he was copying, however, his choice of quotes speaks of his character also:

- Flyleaf of Quintus Curtius Rufus’ 1705 Latin edition of the deeds of Alexander the Great inscribed in James Bickam’s hand: “Quintus Curtius is generally esteemed as an author rather qualified for a declaimer, than an historian, who took more pains to adorn his style & finish his periods than give a true & faithful account of things. Arrian’s History of Alexander is much preferable.”

- Inscription in Joseph Hall’s 1753 edition of his Virgidemiarium by Bickham, critiquing the author: “Which for him, who would be counted the first English Satyr, to abase himself to, who might have learn better among the Latin & Italian Satyrists & in our own poor Tongue from the ‘Vision & Creed of Pierce’s Plowman’, besides others before him, manifests a presumptuous undertaking with weak and unexamined shoulders. […]”.

- Finally, prefacing Bickham’s copy of the play The Rehearsal by George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, a 17th century author, is another biting commentary. It draws on The Rehearsal’s satire, aimed at John Dryden, England’s first Poet Laureate, and possibly critiques 18th century contemporary poets, foremost the unnamed Poet Laureate, possibly William Whitehead (1757–85): “To see the incorrigibleness of our poets in their pedantick manner, their vanity, defiance of criticism, their Rhodomontade & poetical bravado, we need only turn to our famous Poet Laureate (the very Mr. Bays himself) in one of his latest and most values pieces […]”. If Bickham wrote this, he would have been aware that his friend Gray famously declined the position of Poet Laureate in 1757, when it was offered to him before going to Whitehead.

Beside such harsh criticisms, Bickham’s books contain numerous marginal corrections like proof-reader’s notes, which pick out typos, or change the meaning – not obviously for the better – by suggesting alternative words. Bickham “corrects” authors of unassailable status as well as lesser-known names. Ultimately, though, we do not know why Bickham shied away from becoming a published man of letters.

As for the works of his friends Gray, Mason and Hurd, Bickham carried a torch for them. He inscribed the title pages of books gifted to him clearly as “a gift from the author” and had Gray’s Elegy bound together with Mason’s Elfrida and a poem by Thomas Francklin, a Cambridge contemporary, as if in a reunion edition of old friends. Bickham probably never saw his college friends again, but he kept their books. Bickham’s legacy is this collection of books which, as we shall see in the next blog, encapsulates the tensions of his age, caught between remnants of Medieval scholastic traditions and the pressure to educate people across classes and genders for modern times.

Next blog: Which side is the LPL on in the battle between the ancients and the moderns?

© Article written by Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

Resources used:

Paget Toynbee and Leonard Whibley, Correspondence of Thomas Gray Volume 3 (1935)

Margaret Baker, The life and times of the Rectors of Loughborough (2012)

W.A. Pemberton, The Parochial Visitation of James Bickham D. Archdeacon of Leicester in the Years 1773 to 1779 (1985)

[1] Knowledge gained through learning/scholarship.

[2] An official role within the church, along with the income and other assets (such as a house and farmland) which went with it.

[3] A person holding such a role.

[4] Tithes were originally a one-tenth percentage of all agricultural produce which households were required to hand over to the church to support the local clergy. An act of parliament in 1836 converted this tax to a monetary payment. In effect, this was Bickham’s income, and anyone failing to pay their tithe reduced that income. (Taken from website of nationalarchives.gov.uk)

[5] Bickham paid for the renovations from the income he received as rector. It wasn’t uncommon for the clergy to resist making repairs and improvements to the houses they lived in but didn’t own, given that they could simply save the money these cost for their own personal use.

[6] Area of responsibility

[7] The garments worn during religious services by the clergy, their assistants, choristers, etc

Loughborough Parish Library, PR3548.M2, barcode 100834608X.

© Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

Loughborough Parish Library, PR3714.S3, barcode 1008382229.

© Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

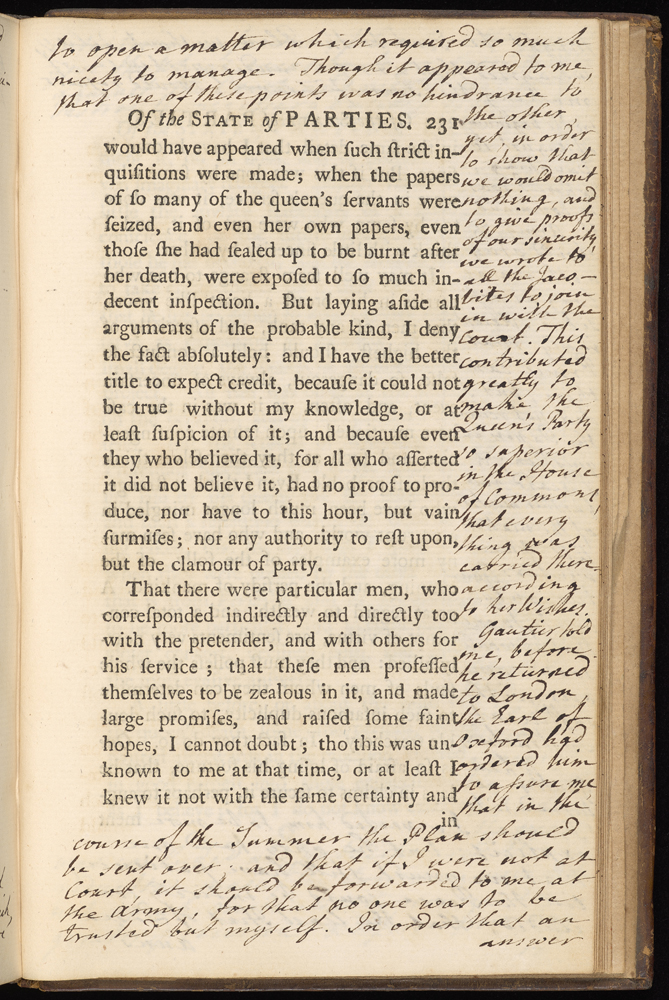

Three pages from a book of political philosophy with margins written in by James Bickham. He is copying from another text, ‘Memoirs of the Marshal Duke of Berwick’ (1779), to use as a parallel reference.

Henry St John, Viscount Bolingbroke, Letters, on the spirit of patriotism, on the idea of a patriot king, and on the state of parties, at the accession of King George the First (1749). Loughborough Parish Library, DA501.B6, barcode 1008382597.

© Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

Previous post: Loughborough Parish Library (2): poor rates and book plates

Next post: Loughborough Parish Library (4): the battle between the Ancients and the Moderns – which side is the LPL on?