Loughborough’s Health in 1848

29 August 2020

The industrial revolution caused towns such as Loughborough to grow rapidly as the newly-established factories drew unemployed craftsmen and women away from their homes in the countryside and into the towns to operate the machinery that was replacing their skills.

This influx of people quickly created overcrowding. The sale of pockets of town-land by the Earl of Moira in the early eighteen-hundreds caused a building boom in Loughborough, infilling veg plots and orchards, yards and alleyways with custom-made buildings, and helping fulfil the need for more and more homes and commercial premises.

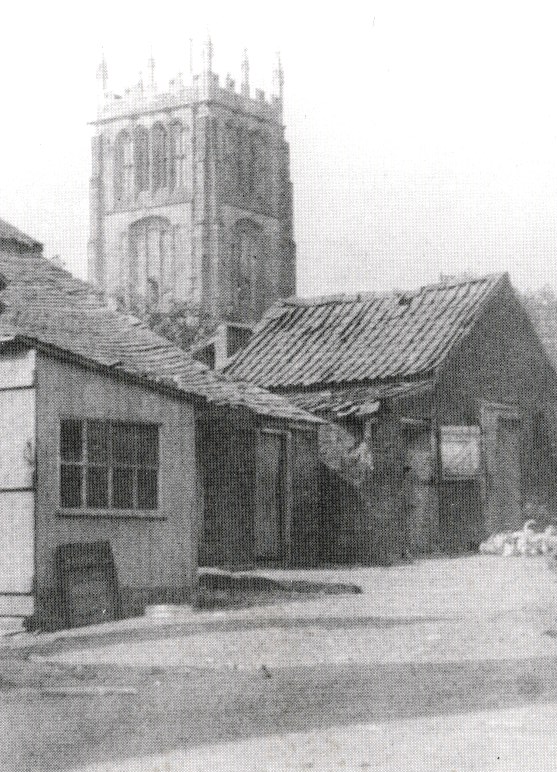

The town became packed with little courtyards of dwellings wedged between businesses. Slaughterhouses stood next to cottages, tanneries beside shops, farmyards shared yards with engineering sheds. Human, animal and industrial waste ran off into cesspools next to wells where families drew water for cooking, bathing, cleaning and laundry. People lived cheek by jowl in hastily thrown together housing with poor ventilation, shared amenities, and little room to move.

Unsurprisingly, mortality rates soared, especially among the poor, as disease spread through this new urban environment.

In 1849 one in five of all children died before they were one year old, irrespective of their class. The average age of death across the population was 23 years 11 months, though this rose to the heady age of 55 years 9 months for those who managed to make it past twenty.

The mortality rate in Loughborough was 28 deaths per every thousand inhabitants (compared to 9.6 per thousand in 1983 and roughly 5.5 per thousand in 2006 for the Borough of Charnwood.)

Public health and sanitation was a national problem, discussed by princes and the aristocracy, the government and ordinary people on the street. A new cholera epidemic sweeping Europe prompted urgent need for reform.

The result was the Public Health Act of 1848, which received royal approval (thereby becoming an Act of Parliament) on 31 August 1848. The Act made recommendations developed from a report by Edwin Chadwick on the sanitary conditions of the labouring population of Great Britain.

The Public Health Act established a national General Board of Health, responsible for advising on disease prevention and with the power to set up Local Boards of Health where needed, to take over and formalise work previously done in parishes by charities and voluntary bodies. The idea for these Local Health Boards wasn’t universally popular, however, largely because of concerns they’d incur costs that would raise local tax rates.

Areas could petition to have a Local Board of Health, requiring ten percent of the ratepayers to sign the request, or the General Board could force a Local Board upon an unincorporated town judged to need one from high local death rates (the benchmark being an average mortality rate of 23 out of 1000 people over the previous 7 years).

Loughborough was one of the towns to petition the General Board of Health, with two hundred local ratepayers signing the request (though interestingly, only one of the town’s doctors). The petition was irrelevant, however, given the high death rate in the town. Loughborough was on the radar of the General Board of Health and the way things had been managed pretty much since medieval times was about to change.

Alison Mott

Read the previous post in the thread here.

Read the next post about this topic here.