A story of scandal behind a Quorn sampler

28 August 2015

Although Quorn Village On-line Museum doesn’t own many artefacts in its own right, we do come across some incredibly interesting items, which people allow us to photograph and which we can then try to investigate. Sometimes stories emerge that provide a fascinating glimpse into the lives of our forebears in Victorian Quorn.

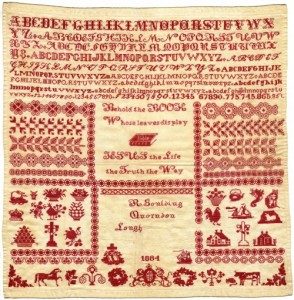

Recently an intricate sampler came to light. It is minutely stitched in red thread and says ‘R Goulding, Quorndon, Lough.’ After the application of a few skills that Sherlock Holmes might be proud of, a story was revealed that involved the fortunes of four orphaned children and a scandal involving the headmaster of Quorn Primary School! It even brought to light a long forgotten murder.

You can read that story here.

Sue Templeman, Quorn Village On-line Museum

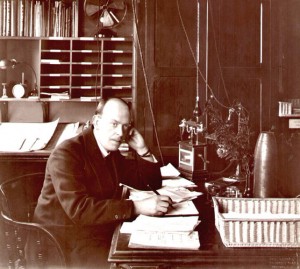

Herbert Schofield and the University: a lecture by Dr G Malcolm Dyson

19 August 2015

In one of a series of lectures on Charnwood’s heritage given at Loughborough Library in the late 1970’s, Dr G Malcolm Dyson, a Professor of Chemistry and leading staff member at Loughborough College from 1928 to 1938, shared recollections of Herbert Schofield and the role he played in advancing education in Loughborough and the fabric of the town. We are very grateful to Mike Gane (Emeritus Professor of Sociology) for sending this to us.

Joining Loughborough’s Technical Institute as its Principal as Britain entered the second year of the Great War, the 33-year-old ‘eccentric but enterprising’ Schofield quickly developed it from an administrative body of three staff coordinating night classes across the town, to a first rate training institution occupying a largely purpose-built site along Greenclose Lane with the capacity to accommodate 800 trainee engineers.

The ability to ‘get things done’ coupled with a willingness to plan things first and worry about the details later enabled ‘Schoie’ and his ‘unholy alliance’ of influential local dignitaries to take advantage of the shortage of a workforce skilled in making precision shell cases. Schofield used this as an opportunity to test out innovative ideas for training workers through hands-on factory work. Starting off by training female munitions workers and, later, soldiers returning from the Front, the model proved successful both during the war and after, providing skilled workers for engineering firms far and wide. The physical and economic benefits of the developments Herbert Schofield set in motion are still evident in Loughborough to this day.

Dr Dyson rounded off his lecture with stories illustrating the character of Herbert Schofield – a hardworking, indomitable man who set himself the task of ‘building an institution of engineering training second to none’ and bent every available resource to this aim. Whilst this could make him a ‘hard man’ with a ‘tendency to autocratic centrism’, Dyson also described Schofield as someone who trusted his staff and left them to get on with their job – as long as they kept him informed of what was going on. ‘Not the conventional portrait of a great man,’ Dyson stated, ‘but […] the man as we knew him. He was human, he was forthright and we all loved him for it and worked as hard as possible to […] help him secure his cherished objective’. That objective was the ‘unique engineering university’ for which the town is so well known and which, Dr Dyson concluded, would never have existed ‘but for the indomitable persistence and courage of Herbert Schofield.’

You can watch the restored black and white archive lecture here.

Herbert Schofield (third from right) beside Geoffrey Fisher, Bishop of Chester, outside All Saints’ Rectory on College Sunday, 1938. To the left of Bishop Fisher stands the Reverend William John Lyon, Rector of All Saints, Loughborough from 1934 to 1958.

Alison Mott

Do you have information, photographs and recollections of Herbert Schofield which could be added this feature? If so, please email history@lboro.ac.uk.

‘Foreign Wizards Play Magic Better’: a story of China

12 August 2015

Loughborough resident Eva Weng shares a story from her family’s history which compliments the recently featured story of Alfred Woodroffe.

“Foreign wizards play magic better.” This is an old Chinese saying. I never got any chance to see wizards, foreign or domestic, playing magic. But my grandma did. One of the most interesting things in my childhood was to listen to her telling about the magic, how it was played, and how it changed the life of her whole family.

My grandma was born in a small town in very remote countryside in China. Even in the turbulent early 1900’s, it was still lucky enough to avoid continuous rebellions, revolutions and civil wars. There was no newspaper or radio. The local people believed China was the centre of the world, surrounded by barbarians, and that China was as quiet and unchanged as this town.

Her father was a typical traditional literati, that meant he was a poet, painter, calligrapher and musician. He could recite thousands of classic poems and tens of classic philosophical books from his exact memory, but he never knew that the earth is round, table salt is Sodium Chloride, or how to calculate the area of a pentagon. It was very likely his four sons would follow his way.

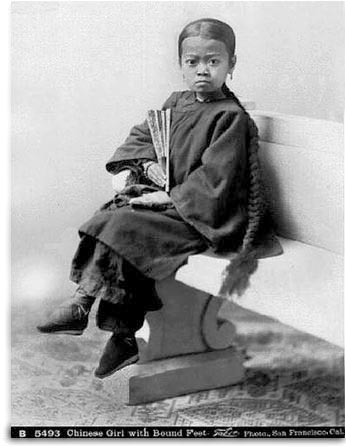

The expectation for my grandma was different. According to tradition, she would bind her feet as small as possible – the ideal size was three inches, a standard of beauty; she would stay indoors all her life, first in her father’s house, after that in her husband’s house, never going out. That was the typical life for a lady.

But this was changed by some strangers, men and women. Nobody knew how and why they came to this backwater. They tried to visit every family, although most families did not let them in. They spoke Chinese, but they did not look Chinese at all. Even after 50 years, my grandma still remembered vividly how amazed she was when one of the ladies visited her family. “Wow! Gold grows from her head! Her eyes are sapphires! She must be a fairy lady!”

It seemed most of the other local people did not have such a romantic impression of these newcomers. They called them “foreign wizards and witches.” Those with more hostility called them “foreign devils”.

These foreigners established a church, a school and a hospital, all of them quite small, but still empty because few people went there. Most people believed an old saying “if someone looks different, his thoughts must be different”. As you know, Chinese tradition doesn’t honor difference so much. They like harmony. Even now, if you go to China and somebody says you are different or extraordinary, you’d better not to take it as a compliment. It is very possible that he actually means you are odd.

Indeed, the thoughts of these foreigners were very different. They tried to persuade parents to unbind their daughters’ feet, and to send them to school. They told them mathematics and science were as important as literature and art. They told them medicines do much more good to the sick than the talisman from the temple do. They told them China was not in the centre of the world and there were many countries like China. They were from one of them, England.

Few believed them, until a big flood in 1931. That was the deadliest flood in Chinese history, it affected more than a quarter of China and caused more than 3 million deaths. The small town survived this disaster only to see another – a wide-spread outbreak of Cholera. The local people did not have any idea about the reason for Cholera and had no way to treat it. Their only method was to quarantine the sick, leaving them to die, but this could not stop the plague.

Then those “foreign wizards and witches” played their magic. They took all patients to their hospital and treated them. Local people were very surprised at first, but soon came to help. One of them was my great-grandpa. His house was even partly used as a hospital. Some patients died, but most of them recovered, and the plague was eliminated finally.

After that, my grandma and her four brothers went to the English school and her father became one of the main donors to the school and hospital. He never entered the church and he died a Confucianist, but he was quite happy to see his wife and five children become Christians.

After graduating from the small school, my grandma and her four brothers went to Shanghai and Nanjing for higher education. They were the first generation in this family who saw the world out of the town. They became a senior police officer, a bank manager, a teacher, an engineer and a diplomat.

When they left the small town, no girls there had their feet bound, all children went to school, the hospital had expanded and was training local people as nurses and physician’s assistants.

When my grandma once asked her father why he decided to send his children to that English school he said “maybe foreign wizards play magic better.” Indeed, they not only played magic better. They played better magic.

Eva Weng

Read the story of Alfred Woodroffe who left Loughborough to become a Baptist Missionary in China in 1897.

Read an article on the Chinese custom of binding girls’ feet by the Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco.

Photograph of ‘Chinese Girl with Bound Feet’ taken in San Francisco. Image from the website of the Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco – http://www.sfmuseum.org/chin/foot.html

Engineering as a Career: Brush Recruitment in the 1940s and 50s

4 August 2015

- Left to right: Derek (?) Sutton, Derek Hall, unknown, Roy M Horne; kneeling – Arthur Marshall (chargehand), unknown.

- ‘Apprentices at Craft Training Centre enjoy mid-morning break’.

- An aerial view of the Brush Falcon Works site on Nottingham Road in the late 1940s/early 1950s

Loughborough resident Mr Roy M Horne has sent in a copy of ‘Engineering as a Career‘ – an old brochure produced in the late 1940s/early 1950s to advertise apprenticeship opportunities at The Brush. A former Brush apprentice himself, Mr Horne features in one of the photographs in the brochure.

Mr Horne came to Loughborough from Barnsley in 1947 and spent his first six months at the apprentice training centre in Regent Street. He boarded at the Gables on Forest Road, one of two hostels operated by the Brush at that time. Formerly a family residence, the Gables is now used to accommodate Loughborough College students.

An apprenticeship is a way for unskilled – often young – workers to learn the skills of their chosen career whilst at the same time earning a wage. Apprentices work alongside members of the skilled workforce, instructed by them and practicing skills they learn more about during frequent periods of study at a local college. Apprenticeships are offered in many different areas of the world of work and trainees often work their way through several different processes of a company before specialising in one specific area at the end of their training.

The Brush was just one of a large number of firms in the town which trained its workforce in this way. The programmes of study they followed built on the earlier, groundbreaking scheme initiated at Loughborough’s Instructional Factory by Herbert Schofield in 1915.

The Brush continues to train apprentices, both school leavers and at graduate level, who still learn through a mixture of on-the-job training and a programme of study delivered by Loughborough College. Whilst in Mr Horne’s day all engineering apprentices were male, it is much more common for female students to take up engineering apprenticeships.

Read Mr Horne’s memories of his apprenticeship and subsequent career at the Brush.

Watch a clip of the Brush Electric Company’s workforce leaving the Falcon Works in 1900.

Read about the Gable’s earlier history as a family residence.

Do you have any information, stories or pictures we could add to this feature? If so, email us at history@lboro.ac.uk.