Fishing in childhood

29 June 2020

Dad would take us fishing by the canal bank off Nottingham Road. The three of us, myself and my two sisters. Mum would never join us in those days, she hated the canal and would have preferred us all to go to the park.

Three nets and a jam jar with string tied around the neck. After all, you had to take your catch home.

For some time we would stand gazing into the water in the hopes of spotting a stickleback. Later, a more effective method evolved, namely running the net along the concrete bank – a sort of trawling – which tended to work better.

David Taylor

How to Catch a Fish

You might catch a fish if you hold your breath,

don’t talk, whistle or sing, you will scare it away.

They like to lurk in the deep, dark places

and also to bask in the sun-dappled shallows,

especially if there are other fish to play with.

Don’t move quickly, you will scare them away.

Just hover, your feet planted firmly apart,

moving the net slowly and ever so gently

like the wavering river weed where it might hide.

Don’t dart after it and stir up the mud

from the bottom in a cloud

so you can’t see the fish.

They will all swim away.

Maybe it’s not the day

to catch a fish.

And there will be trouble

if you should fall in.

Jean Taylor

They called it ‘Fisherman’s Rest’ they did,

An old bridge crossing a stream.

The stream was great as a tiddlers’ place,

But nothing as big as a bream.

In the summer hols we would wander down,

Terry and Ernie, Buster and me,

Carrying nets and a jam jar or two,

‘Cos fishing there for us was free.

Leaving shoes and socks on the river bank,

And with water up to our knees,

We would stand for ages, nets in our hands,

Never worrying if we might freeze.

Now and again a fish would be caught,

A stickleback slower than most,

Would land in the net, be transferred to a jar,

It’s catcher with a moment to boast.

End of the day we would put the fish back,

They weren’t big enough for us to eat.

And anyway fun was the name of the game,

We’d come back any time we could meet.

David Parkin

Loughborough United Reformed Church

28 June 2020

The United Reformed Church – formerly Loughborough Congregational Church – opened on Frederick Street in July 1908.

At this point, Congregationalism had existed in the town for 80 years, its early days being ‘full of hardship and trial.’*

After meeting in rooms in Mill Street and Sparrow Hill, the congregation had opened a chapel in Ashby Square on the site of the former cockpit. Built in 1828 when the congregation were more commonly known as the Independents, the old chapel was subsequently used as the Masonic Hall.

The Gothic style Frederick Street church and adjoining hall were designed at a cost of about £5000 by Loughborough architects Barrowcliff & Allcock, who also designed the nearby Loughborough Town Baths and Carnegie Library, as well as Rosebery Street School.

The move to Frederick Street was ‘no little thing to embark on’, leaving the congregation owing in the region of £2,500 (the equivalent of approx. £3000,000 today) for its construction. The pastor at the time of the move was the Rev W J Wray.

The new church was officially opened on Wednesday 15th July 1908. Sir Joseph Compton-Rickett preached at the day-time opening service. He was ex-chairman of the Congregational Union and a former businessman who had entered politics as a Liberal MP. He later became Paymaster General in Lloyd George’s wartime government.

After the service, a large number of people sat down to tea in the school rooms and this was followed in the evening by a meeting at which Professor David L Ritchie spoke. Professor Richie was Principal of the Nottingham Congregational Institute, a theological training college for Congregational ministers. The college was founded in 1866 by the Rev J M Paton and now bears his name.

The following Christmas, the Echo reported that the choir of the Congregational Church gave a performance of ‘The Messiah’, conducted by Dr Paltridge.

In the 1950s, the College School used the school rooms behind the church and the huts to the side for lessons until moving to their purpose-built school on Thorpe Hill.

Cubs and Scouts also met in the premises in that period before moving to their own building in Thorpe Acre Village. Brownies met at the buildings in the 80s, too, and the rooms have regularly been used by other local community groups, including the WI and a local dance school. In the late 1980s/early 1990s they became the temporary home for Loughborough’s Salvation Army when their own building was demolished in the Rushes and the new building to replace it was being built. (This building has since become a solicitors.)

In the early 1970s, the Congregational Churches and Presbyterian Churches in England and Wales joined together to form the United Reformed Church.+

Compiled by Alison Mott

*’The Story of Loughborough 1888-1914,’ by W A Deakin (Published by Echo Press Ltd in 1979)

+The website of Loughborough United Reformed Church

With many thanks to members of the Remember Loughborough Facebook Group for additional historical information and anecdotes, including Graham Hulme and Colin Price, Mick Hubbard, Una Hubbard, David Wilson, Janet Grant, Jo Bailey Cole and John Cope.

Read about Sunday services at the church in past days here.

Photograph courtesy of Colin Price.

Can you add extra detail to this article? Do you have photographs or memories of the church on Frederick Street you could share? Email us at lboro.history.heritage@gmail.com.

The Leicester Fortnight

26 June 2020

The much-beloved Leicestershire Workers’ July Fortnight started fifty five years ago in 1965.

An announcement was made that factory holidays in Loughborough, Shepshed and other places in the district were to be changed from the first two weeks of August to the first two weeks of July. This meant that work at such places as The Brush would effectively close down for the fortnight, with many workers boarding the special holiday trains to popular destinations such as Skegness.

The move came as a result of a ballot conducted by Leicester and County Chamber of Commerce. The new arrangement was to be for the next year and 1967, after which the position was to be reviewed. The decision to stage a ballot of employees in factories which closed down for the annual holiday in August – both operative and staff – was taken as a result of discussions between employers and trades unions. A total of 11248 ballot papers were issued, the ballot resulting in 4645 votes in favour of the change and 3894 against.

Holidays were often cheaper in July, and it also had the advantage of avoiding the ‘great rush’ that the Leicester Mercury described just before the holiday fortnight in August 1956, when over ninety percent of rail tickets were already sold at local travel agents and up to five million vehicles were expected to be on the roads nationally.

More than a hundred thousand people left Leicester on holiday in July 1965, the Leicester Mercury reported, with ‘a cool one million pounds’ in their pockets, including holiday pay.

Around ten thousand of them travelled on the nineteen East Coast ‘specials’ from London Road Station, and ‘everyone had a seat’ thanks to a free ‘book in advance’ scheme.

Most people did travel by rail, either because they didn’t own a car or to avoid what the Leicester Mercurydescribed as the ‘nightmare drive to the coast’.

It wasn’t just the factories that shut down in Leicester during the July fortnight. Some offices and other businesses also closed, buses ran on a reduced service, and the city seemed almost deserted at times.

The weather on the East Coast for the first two weeks of July in 1965 was said to be ‘improving after a mixed fortnight’ – but there was no need to miss out on news from home as holidaymakers could still buy an edition of the Leicester Mercury in Skegness and other popular resorts.

Some people from Leicester were also venturing further afield for their holidays by the 1960s, with the Spanish resorts of Lloret, Sitges and Torre said to be popular destinations, along with those on the Italian Adriatic coast.

The Leicester Mercury in typical 1960s fashion concluded its article on the Leicester Fortnight with the following paragraph:

‘The Friday is bound to be a day of tension – for mother who has to cope with packing and meals to eat on the way; for the children who are excited at thoughts of what seems like endless days by the sea; and for father who is expected to do a day’s work, rush home and change, load up the car, and then start on a drive of 200 or more miles, a good slice of it during the hours of darkness… [It] can often become a nightmare for the man behind the wheel.’

Leicester Mercury – 7 July 1964

Article by Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers.

Facts taken from the Loughborough Echo and Leicester Mercury.

Copies of Loughborough Echo are available on microfilm at The Local and Family History Centre at Loughborough Library.

Leicester Mercury archives can be accessed at the Leicester Record Office at Wigston.

A postcard view of Skegness in 1967

Aircraft production at Brush

22 June 2020

My grandfather and my father, both who worked ‘at the Brush,’ often spoke of the products that had been built there over the years. Whilst I could relate to the rail products as they were still being produced, aircraft intrigued me.

There seemed to be little information available and memories had been lost or distorted over the years. A few records in the form of official photographs had survived and had found their way to Leicestershire Records Office, but these were without descriptions.

The research undertaken between 1976 and 1978 – with the help of fellow enthusiasts, aviation professionals and publishers – followed many routes and enough material was collected to publish a small book on the subject.

The following year was the official centenary of the Brush Electrical Engineering Company. I was working for one of its constituents – Brush Fusegear Ltd – and was selected as one of three local historians to research the company history for the celebrations.

See here for a precis of the research information accumulated from the book, centenary research and since.

Tony Jarram

Honorary Member of The Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers Group

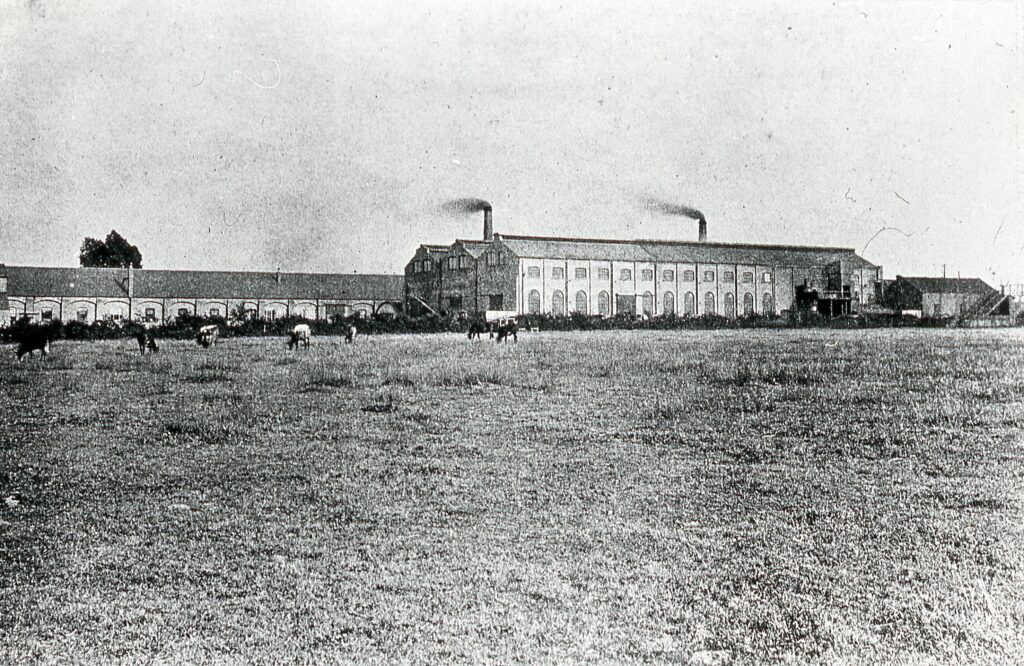

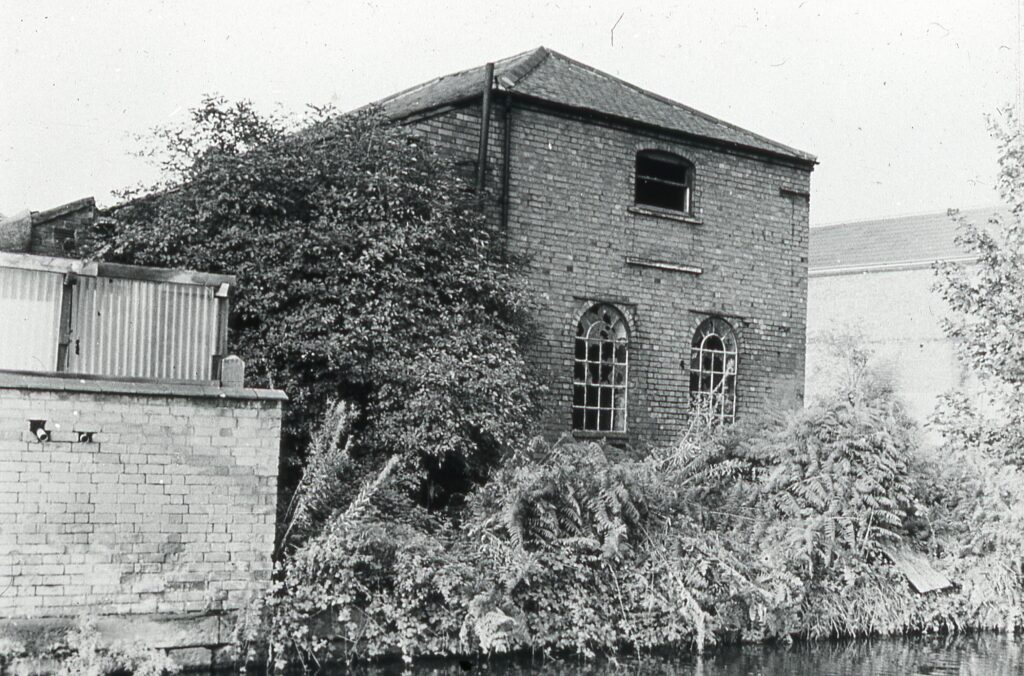

Site of or near to the original Falcon Works, photo taken in 1978. All buildings have since been demolished. (Brian Hope for the Brush Transport Enthusiast’s Club – Tony Jarram Collection)

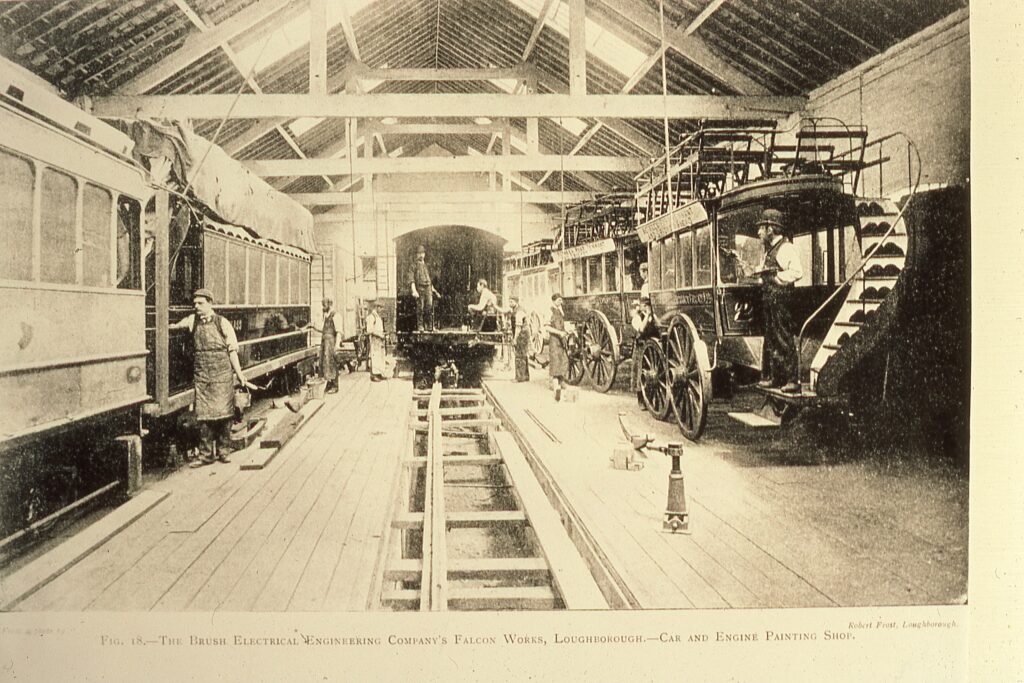

The coachwork paint shop at the Brush works pre-dating aircraft production. In this photograph the products are railway carriages and horse buses. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

The Falcon Works before the outbreak of World War One. Loughborough Meadows in the foreground were used as an airfield to despatch aircraft built at the works. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

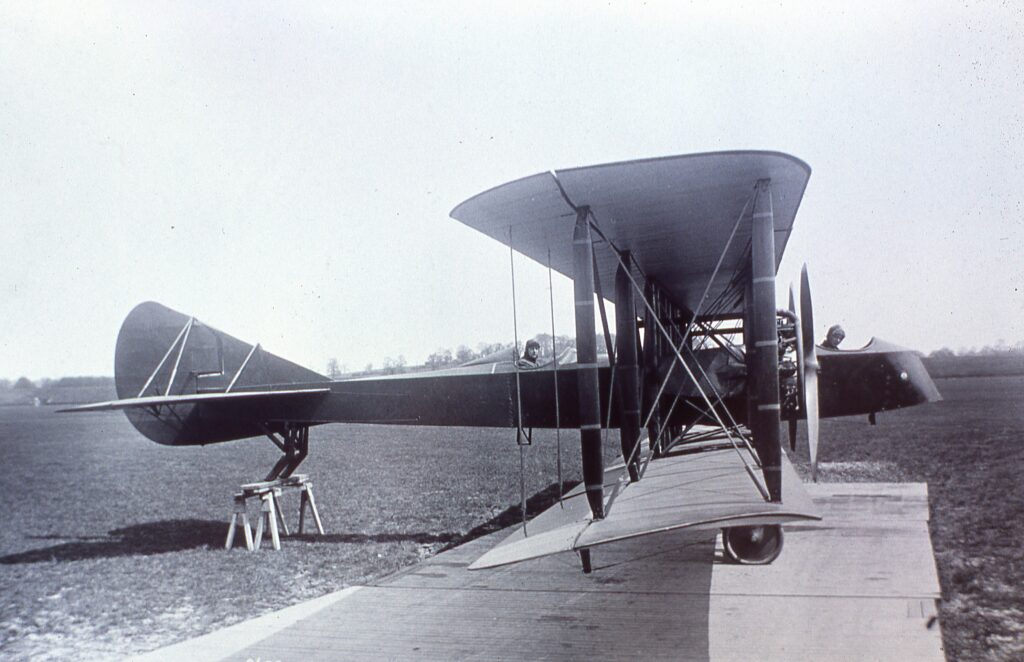

The first Brush built aircraft was this Maurice Farman S.7 Longhorn (3001). It is seen here on Loughborough Meadows in 1916 prior to its delivery flight. Note the Great Central Railway in the background. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

A Farman Longhorn (8939) from the Brush second batch. Clearly visible are the out-riggers that gave the type its name. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

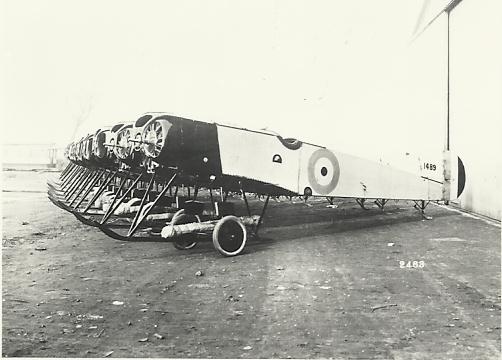

A line up of eight Avro 504C fuselages with 1489 nearest. The small emblem seen on the black engine cowling above the wheel contains the Brush Falcon.1489 was written off at Dunkirk in February 1917. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

Avro 504K two-seat trainer (F2242) is seen here on Loughborough Meadows prior to delivery to the Royal Flying Corps. The pilot is thought to be Teddy Barrs the Brush ferry pilot. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

The sole Henry Farman Astral bomber (9251) on Loughborough Meadows. The ‘top-secret’aircraft is devoid of serial and national identification, but Brush have still added their Falcon logo on the nose. The photograph was taken in March 1917. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

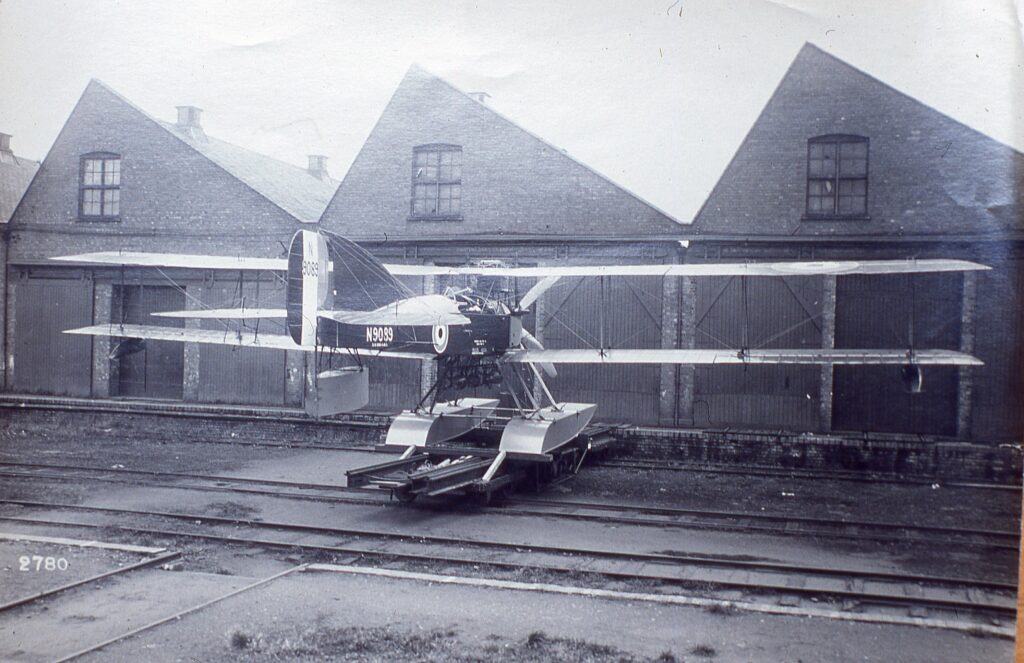

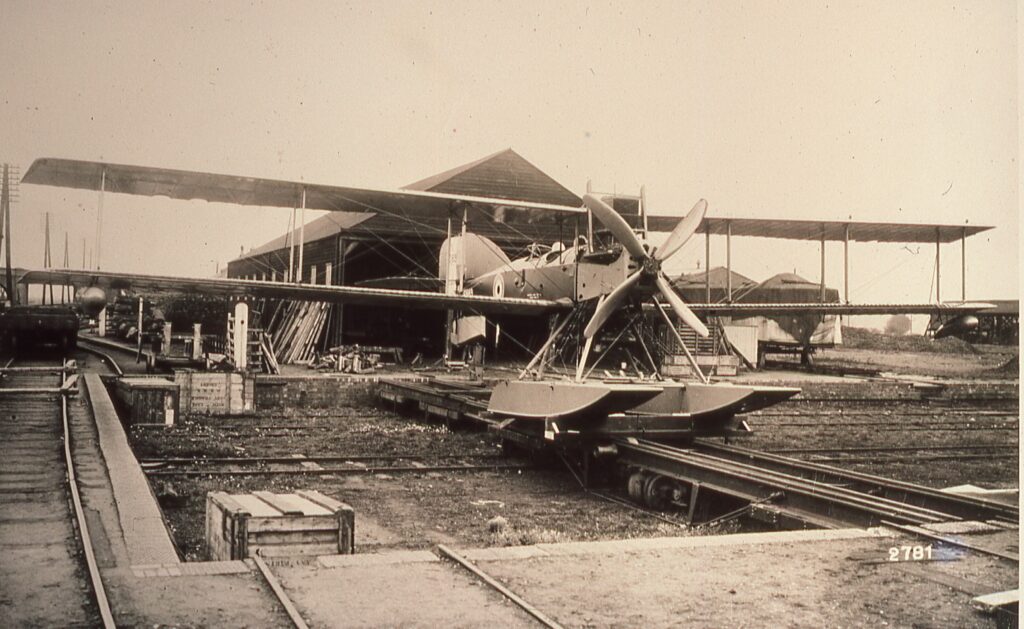

Short 184 seaplane N9089 on the tramcar traverser at the Brush works. This allowed movement between the assembly bays enabling a production line flow. The aircraft is fitted with a 260hp Sunbeam Maori III engine. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

Another view of Short 184 N9089 on the tramcar traverser at the Brush works. The seaplanes would be disassembled and crated for despatch by rail. The Meadow Lane road bridge can be seen in the left background. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

Short 184 N9089 part of the last batch to be built by Brush in 1918. Seen here on the tramcar traverser looking towards Loughborough Meadows. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

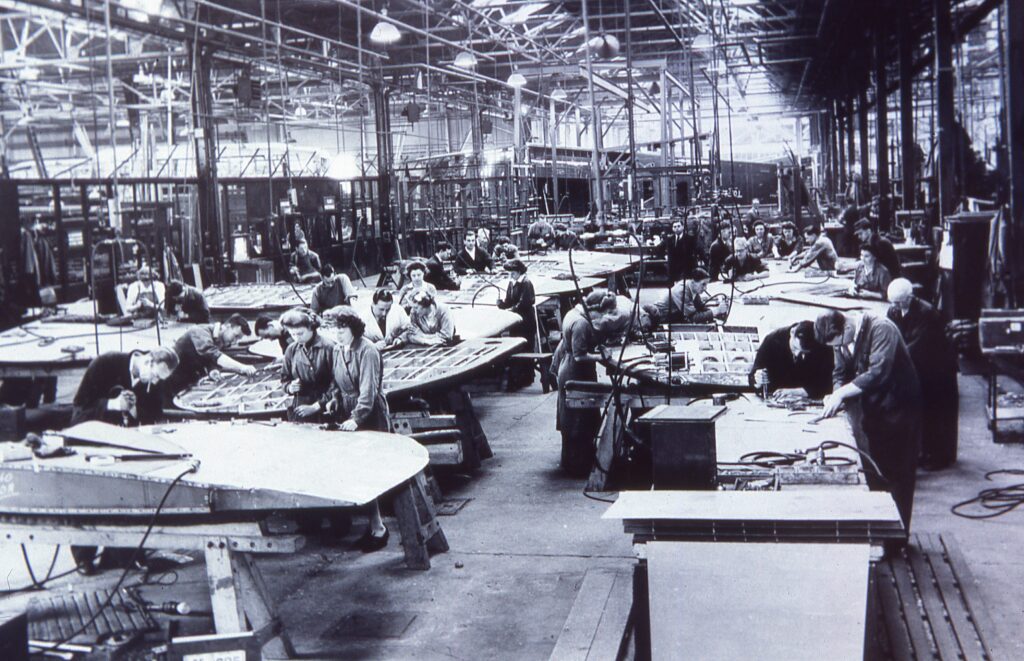

Avro Lancaster wing and fuel tank repair and fabrication in the Brush works during World War II. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

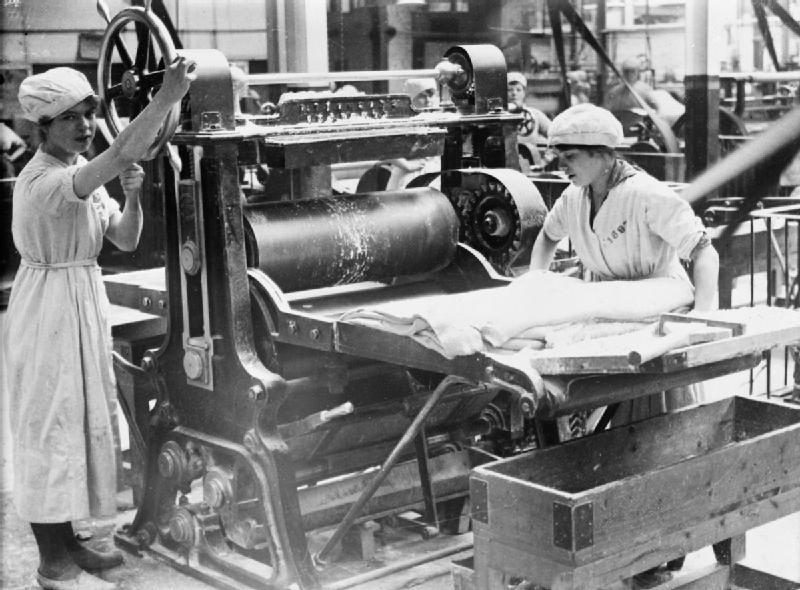

Another view of Lancaster wing and fuel tank repair and fabrication at the Brush works during World War II. Note to use of female labour. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

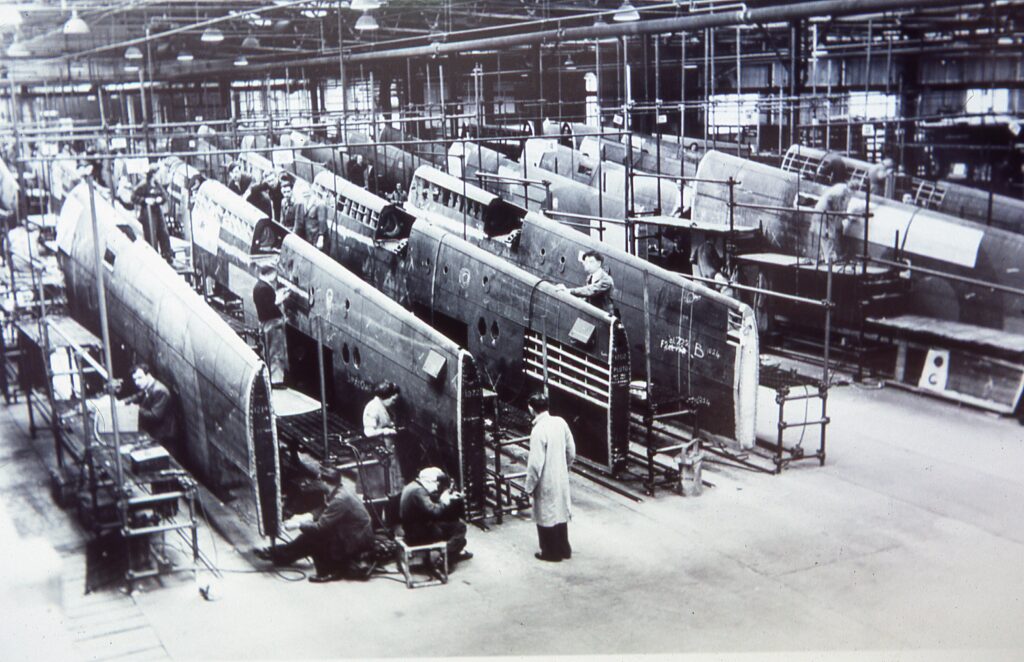

A Handley Page Hampden light bomber fuselage under repair at the Brush works in World War II. There is some speculation that this is P1355 the aircraft in which Sgt John Hannah won his Victoria Cross. P1355 was certainly one of the ones repaired at the Brush works. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

A general view of Handley Page Hampden fuselages under repair at the Brush works in World War II. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

De Havilland D.H.89 Dominie aircraft under construction at the Brush Falcon Works during World War II. The fuselage with inner wings and engines, as seen, would be towed tail first to a specially built assembly facility at Loughborough Derby Road Airfield where they would be fitted with their wings and completed prior to their air test and delivery flight. The nearest aircraft HG719 was delivered on 1st March 1944, via 18MU (Maintenance Unit), to the Staff College Flight at Bracknell. After service at White Waltham and Halton it was sold commercially to Walter Westoby and received the civil registration G-AKMH on 16th June 1948. It served with Westair Flying Services, Bees Flight Ltd, and Mr S.G. Newport before being sold to Zaire in 1964 probably as 9Q-CJK. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

Another view of the Dominie Assembly line at the Brush Falcon Works in 1944. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

The last Brush built aircraft D.H.89 Dominie TX319 at Loughborough Derby Road aerodrome on 2nd July 1946 prior to dispatch to De Havilland’s D.H. Whitney airfield. The aircraft was sold commercially to Peru. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

Another view of Brush built D.H.89 Dominie TX319 at Loughborough Derby Road aerodrome. (Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

De Havilland D.H.89 Dragon Rapide G-AGTM (built as a military Dominie. NF875, in May 1944) seen here at East Midlands Airport on 4th September 1978. Later in the day the aircraft gave a display over the Brush Electrical Machines Gala Day at the Nanpantan Road Sports Ground, Loughborough. The display was organised by the Brush Transport Enthusiast’s Club. (Brush Electrical Machines/Brush Transport Enthusiast’s Club – Tony Jarram Collection)

Dragon Rapide G-AGTM, seen at Duxford, on 28th April 1984, in its former military Dominie livery as Royal Navy NF875 built at the Brush in 1944. (Tony Jarram)

HG691 (G-AIYR) One of the surviving Brush built D.H.89 Dominie aircraft seen here at Duxford in 2011 (Tony Jarram)

Read an article by Tony about the origins of the Brush here.

Origins of the Brush Electrical Engineering Co Ltd

22 June 2020

To study the history of the Brush Electrical Engineering Company Ltd it is necessary to follow two different paths. One originating in England in the Leicestershire town of Loughborough and the other on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean in the USA city of Cleveland, Ohio.

The origin of the Loughborough operation was a small woodyard c.1851, owned by a Mr Capper, situated between the Derby Road and the Loughborough Navigation near and was known as the Regent Street. This was acquired by Henry Hughes and known as the Falcon Works.

There are a couple of theories of why the name Falcon was used. One theory is that it was the name of a canal fly boat that served the works wharf and the other is that Falcon House was the name of Hughes wife’s former home. The Falcon Works manufactured coachwork including ‘dobbin carts’ and small steam locomotives with boilers locally manufactured by Huram Coltman.

Expansion of the business required a larger site and Hughes transferred his works in 1865 to a new location, alongside the Midland Railway. The Falcon Works name was retained.

Hughes, trading as Henry Hughes and Company Locomotive Engineers, soon acquired a good reputation for the quality of the coachwork and the steam locomotive business also continued although not at the rate of some of the competition. Steam tramway engines were also built. The coachwork part of the business was soon building a steady stream of horse tramcars, railway wagons and horse drawn wagons, but in the 1870s there was a slump in trade and the company was over capitalised.

At this time there were great developments in the fledgling electrical industry and one of the pioneers in this field Charles Francis Brush was developing dynamos and arc lamps and had completed a number of electric lighting installations.

In 1879 he established a UK company in Lambeth London known as the Anglo American Brush Electric Light Corporation. Here his company continued to make a variety of electrical products, to Brush’s own design or those of his chief of test William Mordey. These including dynamos, alternators, transformers, arc-lamps, regulators and even set up an incandescent light bulb manufactory at Portpool Road manufacturing to the designs of Lane-Fox. The Brush products were also used to illuminate many buildings and the Thames embankment was lit by electricity generated from the Brush factory in Belvedere Road.

Back in Loughborough Hughes’ company was taken over by Norman Scott Russell in 1883 and renamed The Falcon Engineering and Car Co Russel continued to build steam tram engines and extended the coachwork production.

By 1889 thoughts turned to the widespread introduction of electric tramcar systems and coincided with the expansion of local electricity schemes replacing gas lighting.

The Brush factory in Lambeth was restricted by the expansion of the railways on the eastern part of its site and was looking for a new home and saw the opportunity to amalgamate with Falcon at Loughborough. In 1889 The Brush Electrical Engineering Co Ltd Was formed with Brush and its workers moving to Loughborough. New workshops, ‘ The London Shops’ were built on the Nottingham Road, or southern, side of the site to house the Lambeth production.

The following years saw Brush becoming a major supplier of both electrical engineering and coachwork. The latter saw Brush as the second largest producer of tramcars in the UK and the biggest producer of tram trucks (bogies or wheelsets).

by Tony Jarram

Honorary Member of Loughborough Library Local Studies Group

See a film of the Brush workers in 1900 here.

Read about a strike at the Brush in 1906 here.

(Brian Hope for the Brush Transport Enthusiast’s Club – Tony Jarram Collection)

(Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

The Falcon Works before the outbreak of World War One. Loughborough Meadows in the foreground were used as an airfield to despatch aircraft built at the works.

(Brush official photograph/Leicestershire Records Office – Tony Jarram collection)

Richard Crosher: businessman, philanthropist and churchwarden

21 June 2020

Loughborough’s population grew so rapidly in the 1820s and ’30s it was decided that a new parish was needed.

Emmanuel College, Cambridge – patron of the living of Loughborough – agreed that All Saints Parish could be split in two and that the new parish could take the college’s name. Thus Emmanuel Parish was born and the Revd William Holme, Rector of All Saints at that time, was tasked with dividing up All Saints.

In doing so, he sought the support of Richard Crosher, a parishioner and philanthropist who was active in the life and work of All Saints parish and the wider town.

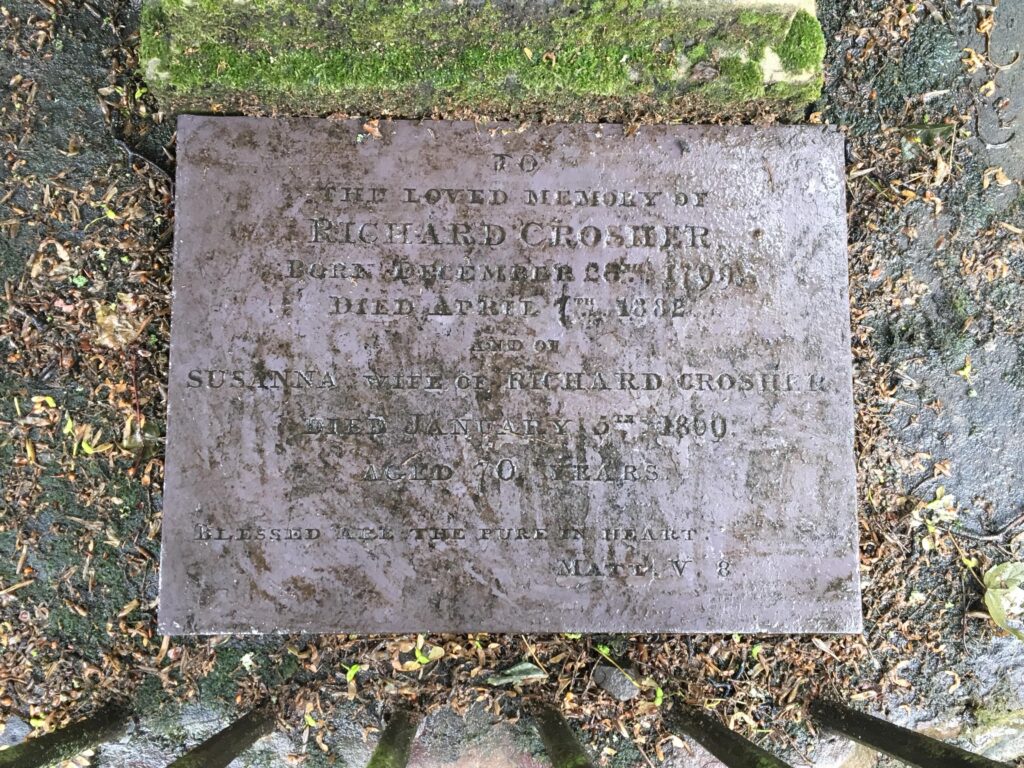

Born in the village of Newbold Verdon on 28 December 1799, Richard is recorded in Pigot’s Directory of 1828/9 year as a tea and grocery dealer with premises in Loughborough Market Place.

He was also a wholesaler in partnership with a Mr Clarke, winning contracts with the Poor Law Guardians – an indication he was trustworthy – for the supply of flour. Business success enabled Richard to support many causes in the town, as well as to have a handsome house built close to Emmanuel church. This house – Forest Field – still exists today, being the core of William Davis’s headquarters on Forest Road.

Emmanuel parish would need hard-working churchwardens to support the new Rector and one position was given to Richard Crosher, as can be seen in an advertisement from the Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire and Derby Telegraph, Loughborough’s local newspaper at that time:

Emmanuel Church. The inhabitants of Emmanuel parish are hereby informed that every arrangement is now made for the celebration of all the Offices of the Church; namely, Baptisms, Marriages, Funerals, etc.

Loughborough being divided into two parishes for all ecclesiastical purposes, it is requisite for persons residing in each division to confine themselves for the above purposes to their own parish church.

Churchwardens Thomas Warner, Richard Crosher, December 7 1838.

Sadly, by 1838 Richard and his wife Susanna had lost both their children – four-month-old Susannah in May 1830 and six-year-old Edward in November 1834. It’s possible that this sadness may have influenced how Richard used the time not taken up by his business.

He was a long-standing member of the Management Committee of the Governors of Loughborough Hospital, acting as one of two ‘visitors’ whose duties included inspecting hospital accounts and authorising payments each week.

He was part of a group of people working in the early 1870s towards setting up a convalescent home for poor patients recovering from treatment in Loughborough Hospital, and one of the first members of the administrative committee when it opened on Maplewell Road in Woodhouse Eaves.

He was elected by the town’s ratepayers to serve on the Loughborough Board of Health, created to deal with the above-average death rate in Loughborough caused by inadequate sanitation.

And he was an early advocate of education for girls, arguing strongly against allowing the proposed ‘New Scheme for Burton’s Charity’ to absorb funding from the Hickling Charity, bequeathed in 1683 to pay for schooling for poor girls. (The motion, however, was carried through.)[1]

Richard Crosher didn’t ignore the needs of the poor of Emmanuel parish, either, recorded as donating coals for them in February 1875. In the same year he supported the UK Alliance, a temperance organisation established by prominent business people of Loughborough.

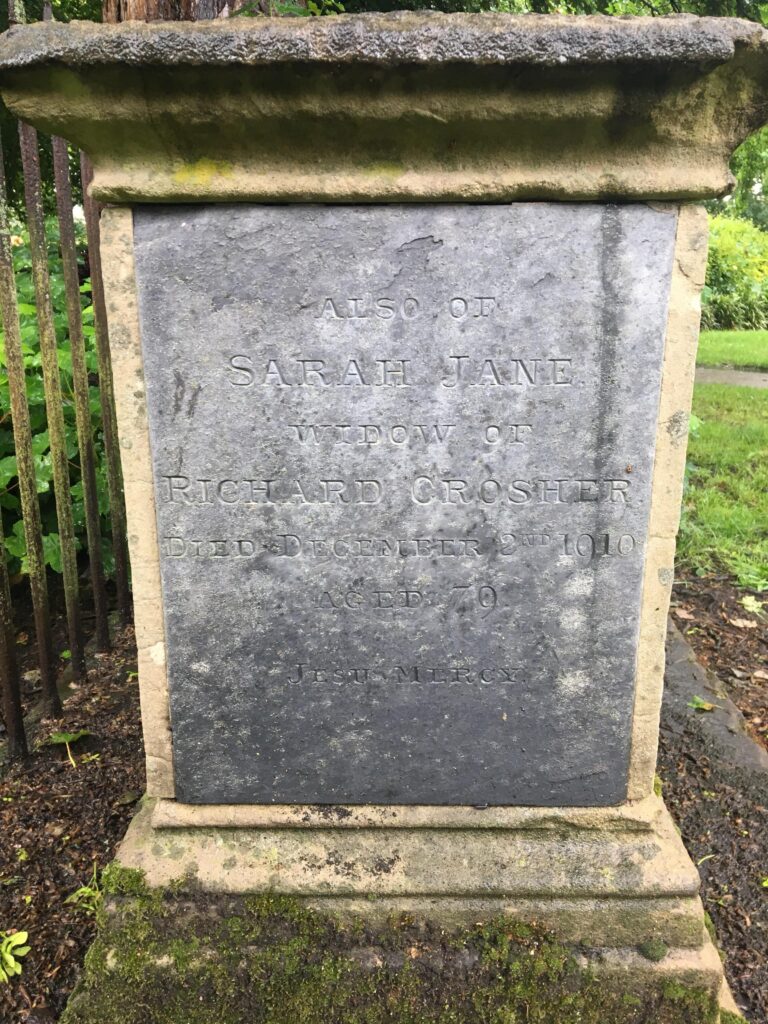

Richard’s wife Susanna died on 5 January 1869 at the age of seventy and was buried in the same plot in All Saints graveyard as her two children. Richard later remarried, his second wife Sarah Jane some 32 years younger his junior.

Richard Crosher died on 7th April 1882. Perhaps significantly, only Richard Crosher and the Rev Robert Bunch – the first Rector of the ‘new’ parish – have memorials in the chancel of Emmanuel church. Richard’s memorial on the north wall of the chancel is a stylised portrait made by T. Brock of London, chosen and paid for by his wife, Sarah Jane. It reads:

“In affectionate remembrance and with tender love this monument is inscribed to the dear memory of Richard Crosher of Forest Field by his second wife Sarah Jane Crosher. He was born on December 28th 1799 and died on Good Friday, April 7th 1882.

In thy presence is the holiness and by thy right hand there is pleasure for ever more. Psalm XVI Verse 12.”

Richard was buried in the family plot in All Saints Churchyard. Sarah Jane Crosher died on 2nd December 1910 aged seventy-nine and was buried with her husband.

Alison Mott

Taken from ‘Richard Crosher’ by Ian Keil, from the newsletter of Loughborough Archaeological and Historical Society, Spring 2011.

See the original article here.

[1] As reported in The Loughborough Advertiser in March 1873

Women at Work in WW1

19 June 2020

In 1914 women in Britain could not vote, study at university or legally enter a profession.

But women did work – as domestic servants, shop workers, in factories and of course at home. The movement for women’s suffrage had gathered pace since 1910. The outbreak of the First World War divided the movement and overtook their protests.

Between 1914 and 1918, an estimated two million women replaced men in employment, resulting in an increase in the proportion of women in total employment from 24 per cent in July 1914 to 37 per cent by November 1918.

Women were required to make a significant contribution during the First World War. As more men left for combat, women stepped in to take over ‘men’s work’. The government used propaganda films to encourage women to get involved.

Jobs carried out by women included farm and factory work, many women worked in munitions, allowing for a rapid rise in production; they also worked on maintaining coal, gas and power supplies. Still others took on work in transport or offices. To women, the First World War resulted in a social revolution.

(by Lewis, in Public Domain from Wikimedia)

Article by Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers

A Loughborough Chimney Sweep

15 June 2020

Loughborough Library Local Studies volunteer Christine Harris shares her research on her ancestor – Benjamin Newton – who was a chimney sweep in Victorian Loughborough

My great-great-grandfather Benjamin Newton was born in Nottingham in 1839 to parents Isaac and Maria Newton. His father Isaac was a stocking framework knitter who became involved with the Chartist Movement and was transported to Australia in 1845.

Benjamin and his brother William were placed in the workhouse in Mansfield and remained there until, in 1850, a Loughborough chimney sweep, Robert Clark of Baxter Gate, came looking for apprentices. So it was that Benjamin became an apprentice when he was just 12 years old.

Benjamin was a chimney sweep all his working life and by 1871 he was running his own business in Fennel Street. By 1881 he had moved to Bridge Street and his son William had joined the business.

William went on to be a chimney sweep for 60 years and his son Frank then joined the business until his retirement in 1957. Thus ended a 107 year-old Loughborough family business.

Over the years, the Newtons swept chimneys for many of the county’s large houses. Garendon Hall, Beaumanor Hall, Staunton Harold and Prestwold Hall were among those they worked in.

Christine Harris

Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers

Read about the difficult life led by apprentice chimney sweeps here.

Rothley Church Memorial Floor Tiles

14 June 2020

- The Chancel is on the right. The window on the south aisle is above the position of the memorial tiles.

- The window above the tiles. Installed in 1897 at the bequest of Ann Greave in memory of her parents Thomas & Lucy Paget and the long association of the Pagets with Rothley. The very colourful glass at the top is held to be the last remnants of medieval glass from the church.

- The interior of Rothley Church showing the position of the tiles at the east end of the South Aisle.

In 1897 a new window was fitted into the South Aisle of Rothley Parish Church. The window marked the long association of the Paget family with Rothley and coincided with the national celebration of the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria’s reign.

Underneath the window, in the South Chancery of the church, are sited 26 encaustic tiles, (i.e. decorated by burning in colours as an inlay, with coloured clays or pigments mixed with hot wax), which were specially commissioned to commemorate the lives of individuals associated directly or indirectly with the church. In 2011 Terry Sheppard of the Rothley Heritage Trust made a photographic record of the tiles and researched the individuals named on them. He collected the information into a booklet and we are indebted to him for making that record available here – Rothley Encaustic Monuments

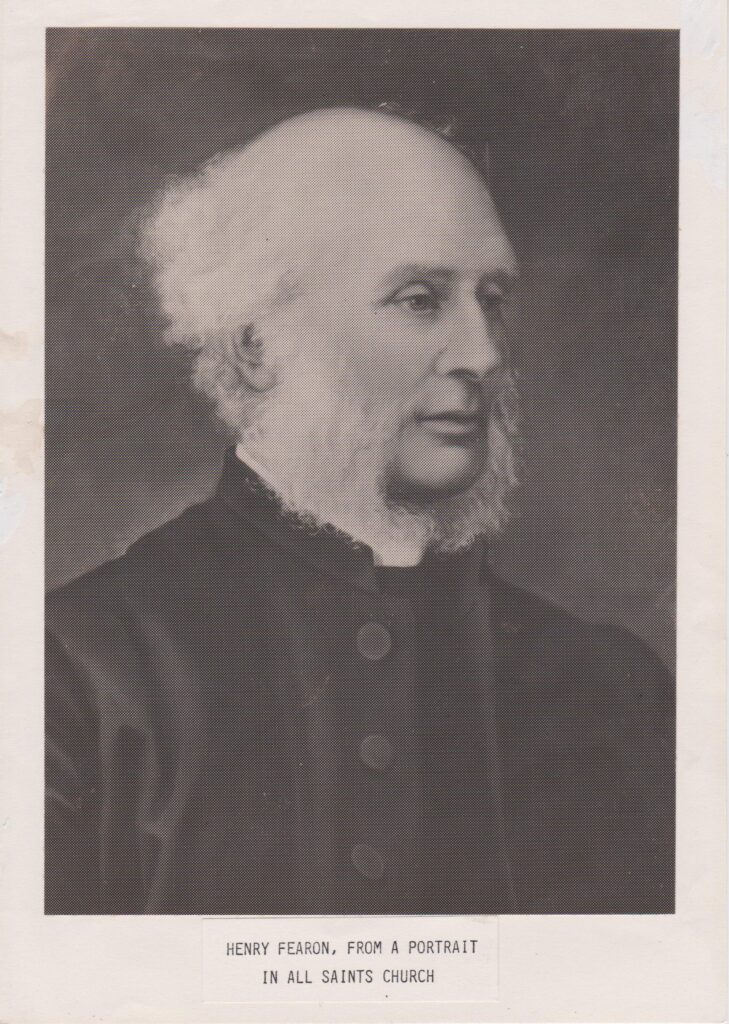

Henry Fearon remembered on the anniversary of his death

12 June 2020

Today marks the 135th anniversary of the death of the Reverend Henry Fearon, Rector of Loughborough’s All Saints Parish Church for almost four decades during the Victorian era and described by some as ‘a maker of modern Loughborough.’

Originally from Cuckfield in Sussex, where he was born on 20th June 1802 to the Rev Joseph Fearon and his wife Jane, Henry Fearon spent many years as a teacher before being offered the living of Loughborough All Saints Parish in February 1848. He was installed as Rector on 3rd May the same year, earning an annual salary of £1000 (equivalent to around £120,000 a year today).

‘Universally respected’ for his ‘kindly sympathy and liberal disposition,’ Reverend Fearon was a driving force behind many of the social and environmental reforms carried out in the town, including education for children of all classes, the betterment of workers and the construction of reservoirs and waste treatment plants to bring clean, piped water to the town and improve public health.

He was Honorary Canon of Peterborough Cathedral from 1849 to 1876, and again from 1884 to his death, as well as Archdeacon of Leicester (1853 to 1884) and a Rural Dean (dates unknown.)

Many of Henry’s ideas could be considered progressive for his time and were shared widely in lectures and articles. He wrote fiction, too, and though he warned against drunkenness, was known to think there was ‘nothing wrong with a jug of sound beer.’

‘He was never intolerant, nor did he undervalue the important work […] being carried on by other ministers of the town. His garden parties at the Rectory were pleasant reunions of all denominations, and Nonconformist ministers spoke of him in the highest terms.’

(Loughborough Monitor & North Leicestershire Gazette, 18th June 1885)

‘He will be greatly missed from amongst us, and we shall be sorry not again to see his genial, kindly face and venerable form.’

(Sermon preached at Woodgate General Baptist Chapel shortly after Henry Fearon’s death)

Henry Fearon was eight days short of his 83rd birthday when he died on 12th June 1885. The whole town is said to have come to a standstill on the day of his funeral, a mark of the affection and respect in which he was held.

Alison Mott

See Lynne Dyer’s article about Reverend Fearon for more information on his life, his funeral and where he is buried. Lynne also wrote an article about some of baptisms and marriages Rev Fearon officiated at, both in Loughborough and his home town of Cuckfield.

This text is largely drawn from ‘Henry Fearon – a Maker of Modern Loughborough’ by Wallace Humphrey, copies of which are available from The Old Rectory Museum, Rectory Place.

Very little would have changed in the intervening years.