Loughborough Flooded – 31st July 1735

31 July 2020

“From Lightning and Tempest, good Lord deliver us, Amen.” A Loughborough prayer from 1735

Extract from: Chapters in the History of Loughborough (1883)’ by Rev W G Dimock Fletcher

The following Memorandum was wrote by Joseph Webster then Clerk of the Parish. –

‘Memorandum that on the last day of July 1735 there happened such an Inundation of Water in the Town that never was heard of by the ancients occasioned by a very great Tempest of Thunder Lightning and Rain which continued from half an hour after nine to half an hour after Three in the afternoon to the great astonishment of all ye Parishioners and Country both, it being on the Market Day Thursday.’

‘The Brooks from the Forest came down with such violence that in the space of an Hour ran through all the houses on the left hand the Malt Mill Lane over the Door Thresholds and thro’ the yards down to the Shambles, and the Fishpool the breadth of the Street against the Shambles ; and both Streams meeting at the end of the Shambles ran over the highest place on the Cornwall ; and thro’ all the Houses Gate Places and low Rooms on the West side of the Market place insomuch that the Waters stood up to their Bed Sides in their Parlers and floated their Vessels in the Cellars and would take an Horse up to the Belly ; and at the bottom of the Swan street up to the Saddle, and ran over the Walls of the Bridge going into the rushes and burst down a Garden wall on the Right hand the Bridge and so got more Liberty and then speedily abated to the Astonishment of all the Spectatours : which might say with the Psalmist, Oh come hither and behold the Works of the Lord what Destruction He hath brought upon the earth.’

‘And likewise –

“Thou art a god that doth foreshow they Wonders every Hour

And so doth make the People know they Virtue and thy Power

The Clouds that were both thick and Black did rain most Plentiously

The Thunder in the Air did Crack his Shafts abroad did fly.

To conclude from Lightning and Tempest from Plague Pestilence and Famine from battel & murder & from Sudden Death good Lord deliver us, Amen.”

18th Century Disasters in Shepshed

26 July 2020

As recorded by Rev. Thomas Heath

Originally known as Sheepshead, the settlement was known for sheep farming and took its name from that. An ancient town, mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 as “Scepeshefde”, meaning ” a hill where sheep graze”. Sullington Road is claimed to be one of the oldest paths in the UK.

Shepshed grew up from Medieval times around the wool trade. “The air is very dry and sweet,” wrote county historian John Nichols “and, owing to its vicinity to the [Charnwood] Forest, it is a very salubrious healthy place.”

On Sundays many attend St Botolph’s Church, which dates from the eleventh century, perched at the highest point in the village. The vicar, Rev. Thomas Heath records in the parish registers:

“Sept 30, 1750, this day (Sunday), while I was administering the Sacrament, between the hours of 12 and 1 o’clock, I and the congregation were very terrible of the shock of an earthquake.”

Another dramatic event happened on 30 June 1753, ‘The Great Fire of Shepshed’ rampaged through the village.

“By what means it was occasioned was never with certainty known,” wrote Rev Heath, but “some little time after the fire had begun, a piece of building was set on fire 150 yards distant from the main place of it; and so unexpectedly did the accident happen, that several persons were busy assisting their unfortunate neighbours, when at the same time their own houses were consuming.”

Many of the villagers helped douse the fire – running frantically with buckets from the village pump – but it burned for twelve hours, destroying or damaging some 85 bays of buildings.

Article by Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers.

by Kev 747 – public domain – Wikimedia

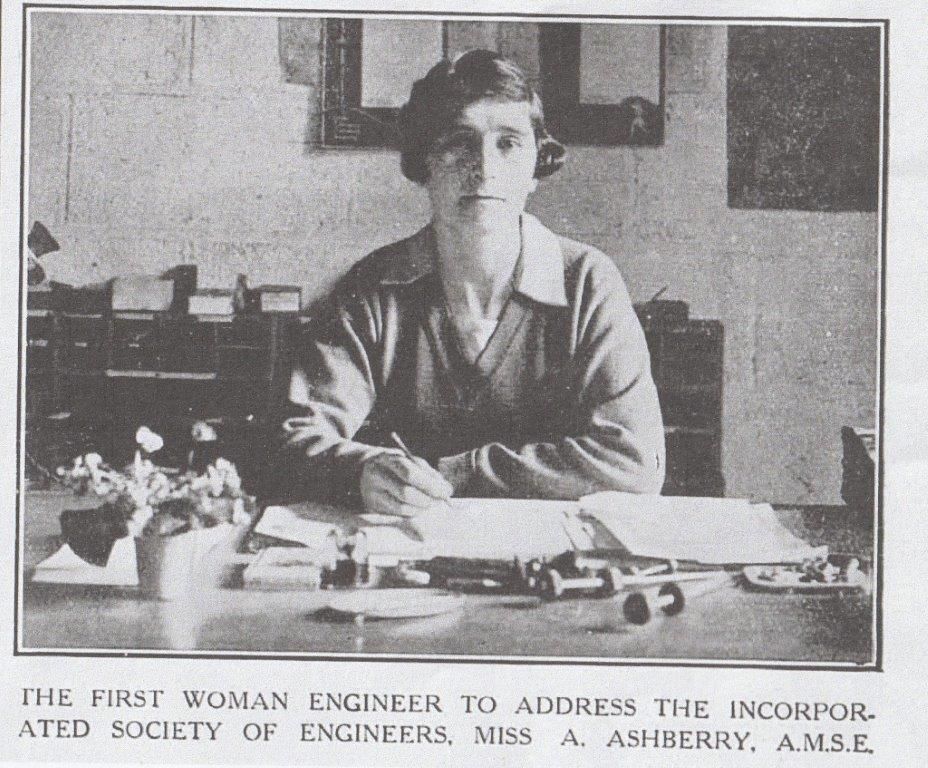

Annette Ashberry (1894 – 1990): a pioneering engineer

24 July 2020

In 1920 Loughborough was awaiting the arrival of a unique and pioneering project, an engineering factory run by and employing only women. Atalanta Engineering Ltd duly arrived with Annette Ashberry as the works manager.

Annette Ashberry had been born in Hackney in 1894 to a large Jewish immigrant family from Russia. WW1 proved tragic for her family – two of her brothers were killed in combat – but for Annette the war also opened doors to her future career. Like many other women she worked on munitions, initially at Park Royal in the shell section, but her keen interest and aptitude in engineering led to a move to Rugby by British Thomson-Houston, who then transferred her to their new plant in Coventry where she was dealing with magnetos.

However the end of hostilities meant her promising career path was abruptly and cruelly curtailed.

Like many other such women she moved to the Galloway factory in Tongland, Kirkudbright,but it became increasingly clear that opportunities for engineering apprenticeships and jobs for women in engineering simply didn’t exist. The only solution they could see was to open an engineering factory run by only women and employing would- be women apprentices whom they would train. Encouraged by the newly formed Women’s Engineering Society (WES) and especially Lady Katherine Parsons, wife of Charles the eminent engineer, they chose Loughborough because the principal and staff of the Technical College were welcoming and could also offer theoretical training .

The premises acquired in Selbourne Street consisted of a building with a roof, three walls and a dirt floor, inhabited by a horse, two pigs and some chickens. There was no electricity; a concrete floor, front wall and door had to be built before they fixed up gas pipes to provide lighting. The two three horse power engines were fuelled by paraffin. Nevertheless the eight women had a successful first year, making hand scraped surface plates and oil burners. The second year coincided with an economic slump and was close to disastrous. There were with few orders and difficulty in obtaining payments for products they had delivered. The eight staff were reduced to Annette Ashberry and one other woman. The scheme was in severe danger of collapse but bravely they cut their losses and decided to move to London where orders might be easier to find. They moved into an old windowless garage in the Fulham Rd and started again with just three small machines, leaving the door open for lighting and kept warm by oil stoves.

However at last their efforts began to be rewarded. In 1922 Annette Ashberry won a prize from the WES for the design of a dishwasher and obtained her first patent for a vegetable peeler. Then in early 1925 newspapers reported that Annette Ashberry, manager of the Atlanta Co Ltd London engineering concern, had been elected to the Royal Society of Engineers, the first woman to be so honoured. This was a significant and much reported coup.

On October 25th 1926 the Manchester Guardian reported:

For the first time in the history of the Society of Engineers (Incorporated) a paper will be read by a woman before the members at the Society’s meeting to be held in Burlington House, on November 1st at 5.30. The contributer will be Miss A Ashberry.

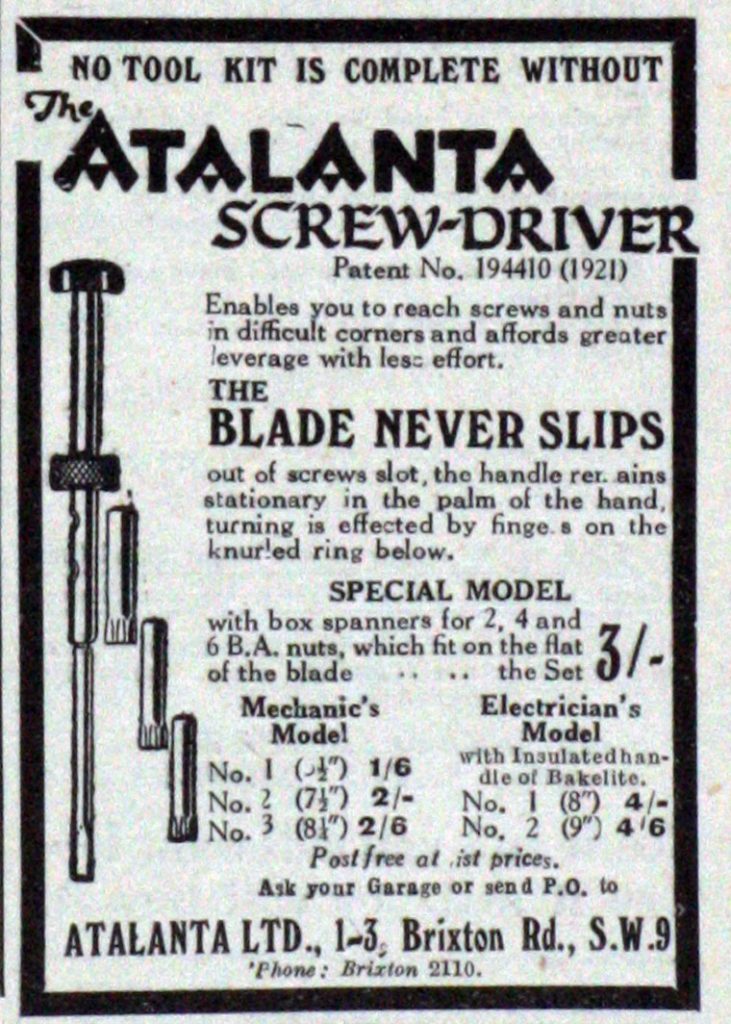

In introducing Miss Ashberry the chairman said that she had gained her membership by qualification and not by favouritism and sex. Described as the managing director and works manager of a firm in Brixton, she chose as her address ‘Some products of a small machine shop’ and proceeded to describe the workings of Atalanta, with particular reference to its products including ‘the Atalanta Screwdriver’ which turned out to be something of a best seller at the time.

In 1925 they were doing well enough to move to larger and better equipped premises at 1-3 Brixton Rd.

In October 1928 there is evidence that Atalanta would be wound up, but in fact, led by Annette Ashberry it continued well into the thirties. In 1929 Atalanta (of Brixton) were exhibiting at the British Industries Fair with the Atalanta screwdriver, the Atalanta Hand Chuck and Atalanta Drilling Jig, and in the same year another first came when the Science Museum in Kensington asked the firm to make a working model of a rotary drying machine.

In 1931 newspaper photographs show Annette Ashberry with Amy Johnson, the aviatrix, on a visit to Atalanta. Amy Johnson expressed regret she hadn’t known about the works and if she had would certainly have worked there rather than become a typist. (Amy Johnson joined Annette Ashberry as the second woman to become a member of the Society of Engineers after her famous flight to Australia in 1930.)

An article in Flight magazine on 29 April 1932 described Atalanta as having a staff of 20 women, carrying out subcontracts for a variety of aircraft companies. In later articles they are described as doing work for Marconi, the Air Ministry and the BBC. All these reports emphasised the women workers were not just machine operators but were being trained in engineering. The last reference to Atlanta and Annette Ashberry I found was in 1935. The reason for its closure is not known, but one could have been the incredibly hard work needed to keep it going. Another could have been the death of Lady Katherine Parsons in late 1933. She had always been a generous and enthusiastic supporter of the scheme. But, anyway, by then Annette Ashberry was already moving into a quite different field.

Living in London flats her hobby had been designing out of the ordinary window boxes. She planted them up with alpines and slow growing dwarf conifers to produce landscapes or miniature gardens. Seeing they had an appeal for flat dwellers, the elderly, and disabled gardeners she obtained premises in Church St Kensington and began a commercial venture which proved remarkably successful. The Times gardening correspondent reported in 1938:

Certainly each production seen in the South Kensington nursery where the gardens are prepared combined the skill of the horticulturalist and the imagination of the artist, and delicate down to the last detail.

In fact she was asked to design and plant up a miniature garden as a birthday present for Princess Elizabeth, to be located at Royal Lodge in the model house, Y Bwthyn Bach, given by the Welsh nation to the Queen as a child. In June 1952 Pathe News reported on her work.

However her growing business was curtailed by the onset of WW2. She returned to engineering again when she was sent to Hoffman’s ball- bearing factory in Chelmsford. Making essential aeroplane parts it was a key target for attacks by German planes, but happily she survived the war and in 1945 purchased a cottage with land in Chignal Smealey, a village on the edge of Chelmsford where she restarted her miniature garden business.

This project was an undoubted success as she developed garden troughs to be placed outside on pedestals, produced fern and bottle gardens and designed alpine lawns. Her nursery and her designs became rightly famous. She exhibited at Chelsea Flower Shows, at The Festival of Britain Exhibition, and appeared on television. Her first book Miniature Gardens published in 1951 was reprinted many times, translated and has become something of a classic. It was followed by six more books which were equally well reviewed.

She died in 1990 at her home, surrounded by her beloved garden.

Annette Ashberry had actually been born Hannah Annenberg but her family changed their surname change from a German sounding name in response to the anti-German feelings prior to WW1. In her gardening business she was known as Anne Ashberry and most people knew nothing of her earlier life as a pioneering engineer. She was a remarkable woman. She battled against so many difficulties, working with real determination to find success in two very different fields.

© Shirley Stewart

April 5th 2018

References

Women’s History Review Volume 12 issue 3 September 2003 p 333-350

Georgina Clarson, ‘A fine university for women engineers:a Scottish munitions factory in WW1’ http/ www.informaworld.com/smpp/content

Engineering for Educated women. The Works and Environment Galloway Engineering Co.Ltd. www.old-kirkcudbright,net/paged/factory.asp

Dorothee Pullinger, http//news.bbc.co.uk/local/southscotland/hi/people and places/history

www.theiet.org/about/libarc/exhibition/women/wes.cfm

www.gracesguide.co.uk/Atalanta

https://worldwide.espacenet.com

https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

https://the guardian.newspapers.com

https://www.the times.co.uk/archive

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspapers

https ://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz

Conversations with people who knew Annette Ashberry including N Creina Glegg, her partner and Lesley Hayward her great niece.

© Mary Evans Picture library

This article was originally published here in April 2018.

William Berridge: lay preacher and local weatherman

19 July 2020

‘As the local weatherman, it was said on the retirement of Mr William Berridge that for more than a score of years he had never missed his daily duty at a certain hour of taking the meteorological readings and sending his recording by cypher telegram to headquarters. He was fellow of the Royal Meteorological Society and was recognised as one of the most reliable observers connected with the office.’

‘On his death in 1904, Loughborough ceased to be the official meteorological station for the Midlands. For some years Mr Berridge was also Secretary of the old Loughborough Town Hall Company and the Loughborough General Hospital.’

‘Mr Berridge’s death was also felt keenly in connection with the Nanpantan Mission Room. He was a licensed lay reader whose constant devotion to the Mission had become proverbial. It was said of him that he had conducted the services there on 900 consecutive Sundays without a break.’

‘”He loved the work and pursued his ministrations in the hamlet with an earnestness and zeal not surpassed by any well-paid minister of the gospel. Although only a lay reader, he was practically the vicar of Nanpantan.”’

The little mission church on the hill and meteorological observations in Loughborough were more than hobbies or recreation to him: they were serious and very earnest duties.

Extract from ‘The Story of Loughborough: 1888 – 1914’ by W A Deakin. (Pub. Echo Press Ltd 1979

Read about Nanpantan Mission Room – now the church of St Mary in Charnwood – here.

Loughborough Family Connections: Nash – Burder – Fison

17 July 2020

A one-time resident of Ashby Road, the Reverend Frederick Gifford Nash was born in Fowlmere, Cambridgeshire on 30th June 1819.

He attended Pembroke College, Cambridge University, was ordained in 1844 and became the Vicar of Diseworth from 1845 to 1851. He married Miss Sarah Eliza Hackett.

On his retirement he moved to ‘Clavering’, Ashby Road, Loughborough where he died on 21st August 1904.

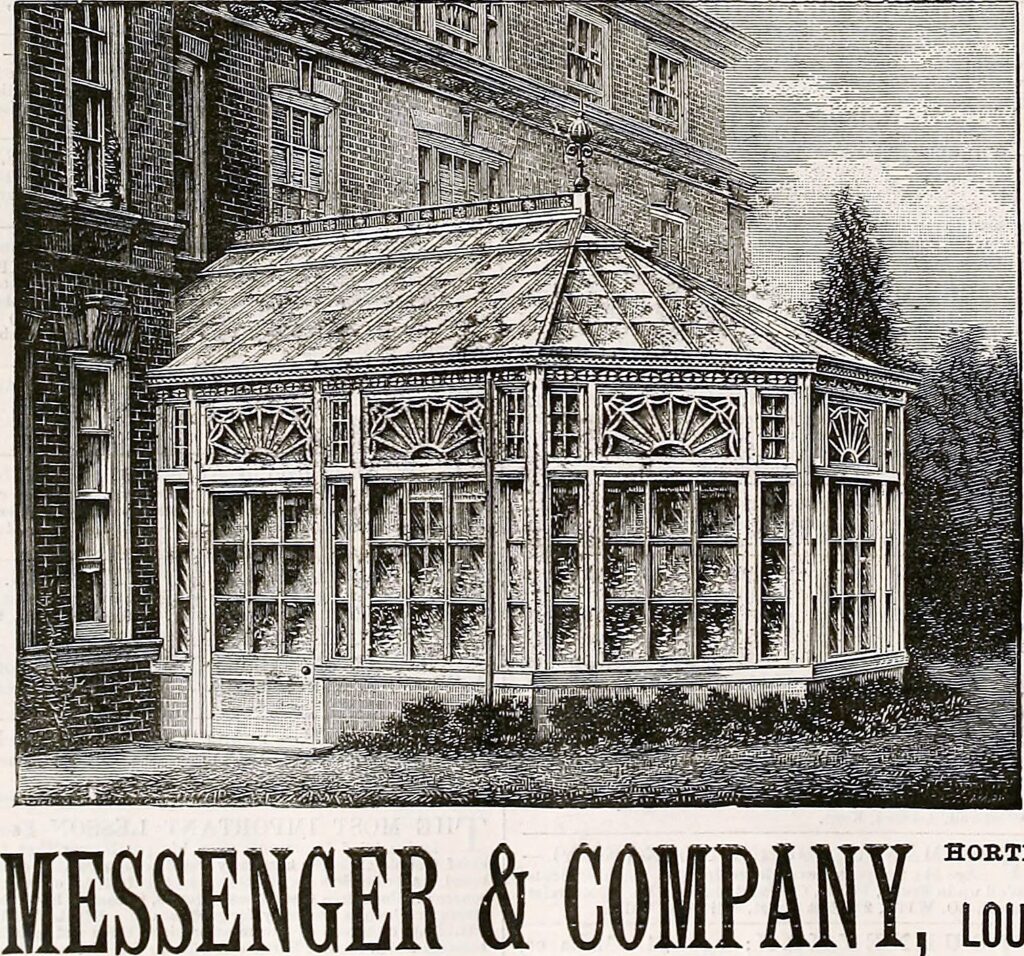

In his will he left effects to the considerable sum of £3786 13s 6d. Reverend Nash’s executors were his son, Reverend Frederick Cordon Nash, clerk, and his son-in-law, Walter Chapman Burder, horticultural engineer.

Frederick and his wife Sarah had daughters who through their marriages connected the Nash family to two influential families in Loughborough. Lucy Maud Nash married Oliver Fison and Elizabeth Jane Gifford Nash married Walter Chapman Burder.

The Loughborough Roll of Honour contains the war record of Captain (Brigade Major) James Frederick Lorimer Fison MC, who was born on 23rd June 1890. He was the eldest son of James Oliver Fison, manufacturer of chemical fertiliser, and his wife Lucy Maud Fison (née Nash).

On 2nd July 1889 James’s parents were married at the Church of St. Mary and St. Clement, Clavering, Essex, where the service was conducted by the bride’s father, the Reverend Frederick Gifford Nash, then Vicar of Clavering. James Fison had two brothers, Frank and John, and three sisters, Madeleine, Florence and Sylvia. The Fison family lived at Stutton Hall, Suffolk, a fine Tudor house overlooking the Stour estuary.

James was a frequent visitor to Loughborough, where a number of close relatives on his mother’s side of the family were living. His aunt, Elizabeth Jane Gifford Nash, had married Walter Chapman Burder, a horticultural engineer and owner of Messenger and Company. They lived at Field House, situated near the Epinal Way/Ashby Road roundabout.

His maiden aunts, Edith and Frances Nash, and his uncle Thomas Nash also lived in Loughborough, as did his maternal grandparents the Reverend Frederick Gifford Nash (retired) and his wife Sarah Eliza. Whether James was ever employed at Fisons in Loughborough is unknown to us but as he was the heir apparent to the Fisons’ empire, some involvement seems likely.

Another of Reverend Frederick Gifford Nash’s daughters, Edith (mentioned above) was a WWI Red Cross Auxiliary at Loughborough Hospital. Edith was among those celebrated in the Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers’ exhibition about the 42 members of the Loughborough Voluntary Aid Detachment (VADs), a county branch of the Red Cross.

Article and Research by Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers.

(Illustration in the public domain.)

Read a blog post by Lynne Dyer about the houses on Ashby Road, including Clavering and Field House.

Shelthorpe School – a Diamond Jubilee

13 July 2020

Shelthorpe Infant and Junior schools were created to serve the community of the Shelthorpe housing estate, built to the south of town by the Loughborough Corporation from 1926 onwards.

The schools were designed by Edward T Allcock of Loughborough, the initial idea being they would stand around two enclosed quadrangles, though in the end these didn’t materialise, as neither did the nursery which also appeared on the original plan.

The Infants’ section of the school opened on 1st June 1933, with headteacher Miss D M Hallam and her staff welcoming fifty children aged from 5 to 7 years old.

By July 1939 the number on roll had risen to three hundred and five, half of whom were above the age of seven. These older children were soon accommodated at Shethorpe Junior School, which opened on 28th August 1939 under the headship of Mr T S Fielding.

Two hundred and fifty children were admitted to the Junior School, with another forty or so turned away through lack of room. The issue of space was exacerbated when within days war was declared and both schools were called on to accommodate the evacuees from Sheffield who arrived in the town on 1st September.

When they reopened on 18th September, ninety-three evacuees and an additional thirty-seven local children swelled the ranks of those already attending the schools. A temporary concrete building was placed on the site at some point during the second world war.

Both the infant and junior schools were extended in 1948 and, in 1975, a community centre was added to site to provide facilities for the use of adults. The infant and junior schools joined together into one school in 1981.

Diamond jubilee celebrations took place at Shelthorpe in June 1993. A special newsletter was published documenting key points in the school’s history and its many great achievements, which included it having one of the most successful community centres in the county.

During those commemorations, the community room was renamed the ‘Wallace Humphrey Room’ in recognition of a much-loved former headteacher and the contribution he made to developing community provision over his twenty-one-year post at the school.

In 2012 Shelthorpe School changed its name to Beacon Academy when it joined the Academies Enterprise Trust national family of schools.

Compiled by Alison Mott

With many thanks to the Humphrey family for the loan of The Shelthorpe School Diamond Jubilee Scrapbook which you can read here.

Read the history of the award-winning Shelthorpe housing estate – designated as a Conservation Area in 1976 – here.

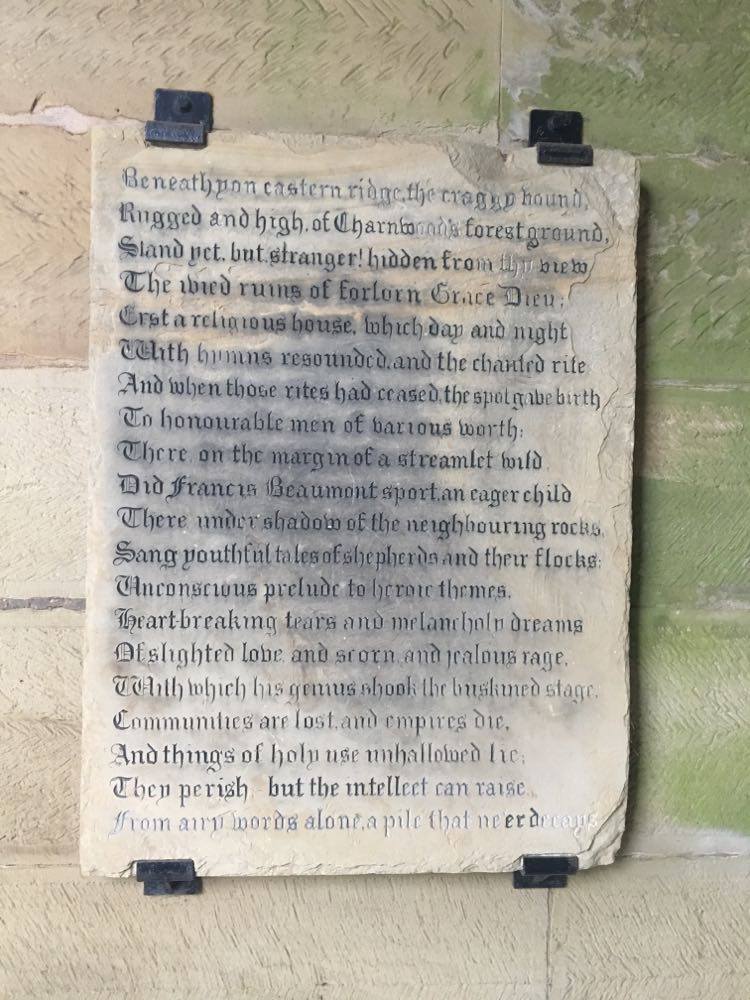

Grace Dieu Priory

12 July 2020

Grace Dieu Priory is a former Augustinian nunnery in Thringstone, Leicestershire, founded in medieval times by Roseia de Verdon, a wealthy heiress in her own right and widow of Theobald Butler, who held extensive lands in Southern Ireland.

Theobald’s death in 1230 made Roseia a ‘femme sole,’ an independent woman no longer under the legal supervision of a man. In 1233 her financial independence was consolidated when she secured the right to her late father’s properties in Leicestershire, Lincolnshire and Staffordshire. Roseia proved to be an extremely capable manager of both these and the dower – widow – lands left to her by her husband, building a castle in Ireland to protect her interests there and securing a financial legacy in England for her sons.

Roseia remained in Ireland for some years, where stories of her ruthlessness and determination became legend. By 1240 or 1241, however, she was in Leicestershire, founding the priory at Grace Dieu which, under pressure to remarry, she decided to join herself.

The priory consisted of a central complex of stone buildings grouped around a cloister – most probably a garden – with the church standing to the northern side, the chapter house* and dormitories to the east, the refectory (or dining hall) to the south and other rooms to the west. Additional agricultural buildings were dotted around the priory site.

With fish ponds in the grounds and farmland surrounding it, the Grace Dieu community would have been independent and self-sufficient, and though the nuns were forbidden from leaving the priory, they’d have experienced a level of comfort and autonomy in day-to-day life unusual for women of the time. Roseia had bestowed the Manors of Belton (in Leicestershire) and Louth (in Lincolnshire) to the priory, and with continued bequests from others over the years, the priory would have grown to be very wealthy.

Roseia de Verdon died in 1247 and was buried at Grace Dieu.

Grace Dieu continued as a priory for almost three hundred years. It was disbanded in October 1538 and its assets confiscated during the dissolution of the monasteries ordered by Henry VIII. At that point, the villagers of Belton removed Roseia’s body from the priory and it was re-buried at Belton Parish Church.

After the dissolution, ownership of Grace Dieu Priory passed to John Beaumont, who converted it into a home, turning the cloisters into a courtyard and the refectory into a great hall, along with other modifications necessary for a family’s country residence. In the 1690s it was bought by Sir Ambrose Phillips of Garendon Abbey and further modifications made. By 1730, the buildings were in ruins and by the 19th century, Grace Dieu had become a nationally-known ‘romantic ruin,’ visited by well-known poets and artists of the day, including William Wordsworth.

During the industrialisation of north-west Leicestershire, the short-lived Charnwood Forest canal cut through the Grace Dieu site, to be followed in 1881 by Charnwood Railway, which closed in 1963.

Since that time, the site has continued to attract visitors – and, some would have it, the ghost of Roseia de Verdon, who is said to regularly make the journey over from Belton Church to her first resting place at Grace Dieu.

Compiled by Alison Mott

*The chapter house was a room where the nuns met daily to hear a chapter of the monastic rule – the guidelines for the organisation of their community.

Sources:

‘Grace Dieu Priory’ by Kenneth Hillier and Peter F Ryder (Pub. Ashby-de-la-Zouch Museum/The Grace Dieu Priory Trust, 2006)

‘Roesia de Verdun: Norman femme sole,’ by Gillian Kenney, Women’s Museum of Ireland website [accessed 11.7.2020]

Read about life in a medieval nunnery here and here.

Photo © Alison Mott

Photo © Alison Mott

Photo © Alison Mott

Photo © Alison Mott

Photo © Alison Mott

Nicholas Alkemade – the man who fell to earth

10 July 2020

This is the story of a remarkable man.

Nicholas Alkemade – ‘Nick’ to his friends and family – is most famous for his fall to earth without a parachute. This was only the start of a series of incredible events, any one of which would have finished a lesser man.

To start at the beginning, Nicholas was born on 10 December 1922 in North Walsham, Norfolk and became a market gardener in Loughborough before the outbreak of war.

He trained as an Air Gunner and was posted to 115 Squadron as a rear gunner on their Avro Lancasters. After successfully completing 14 operations, Alkemade’s crew were detailed to raid Berlin [the event to which the title refers] on the night of 24/25 March 1945.

The aircraft, christened Werewolf by its crew, took off from RAF Witchford, Cambridgeshire at 18:48 and set course for Berlin.

The Lancaster was hit by enemy fire, engulfed in flames and lost control. The crew started to parachute out, but when Alkemade went to get his own ‘chute’ it caught fire and became unusable [as a rear gunner there was no room for him to wear a chute while in the turret], so in a matter of seconds he had to face a terrible choice: perish by getting burnt or make it faster by jumping, as they were at 18,000 feet of altitude. He chose to jump.

He later recalled:

“I had no doubts at all that this was the end of the line. The question was whether to stay in the plane and fry or jump to my death. I decided to jump and make a quick, clean end of things. I backed out of the turret and somersaulted away.”

But Alkemade survived the fall. Possibly blacking out, he fell through the branches of a pine tree into a snowbank. He was picked up by the Germans who initially thought he was a spy. Nicholas was captured and taken to one of the Second World War’s most notorious prisoner of war camps – Stalag Luft III. Here was a secure enclosure operated by the Germans which housed captured Allied airmen. His first experience of the encampment was to be placed in the room where, a week previously, the Great Escape brigade had tunnelled their way out.

Alkemade and the other inmates of Stalag Luft III would later be among the tens of thousands of Allied Prisoners of War forced to march westward – now known as the Long March – some pulling possessions on hastily-crafted sledges, through blizzard conditions and on little food, so the Germans could prevent their liberation by the advancing Russians.

Sergeant A G Nicholas Alkamade, RAF, Prisoner of War Number: 4175, was repatriated at the end of the war and returned to Pearl, who was to become his wife.

All this is quite remarkable but what follows defies explanation of how one man can survive everything that was thrown at him.

Alkemade returned to Loughborough, finding work in a chemical plant. Not long after starting his new job, he again cheated death. While removing chlorine gas-generating liquid from a sump, he received a severe electric shock from the equipment he was using. Reeling away, his gas mask became dislodged and he began breathing in the poisonous gas. An agonising 15 minutes were to pass before his appeals for aid were answered and he was dragged to safety, nearly asphyxiated by the fumes.

Dodging the bullet once again, not long after, a siphoning pipe burst spraying Alkemade’s face and arms with industrial sulphuric acid. He dived head-first into a nearby 40-gallon drum of lime wash to neutralise the acid. Alkemade had first degree burns but had survived again. Sometime later Alkemade was pinned beneath a nine-foot-long steel door runner that fell from its mountings as he passed by, again cheating death.

Alkemade thought that enough was enough and became a furniture salesman with Clemersons Limited in Loughborough.

Nicholas had one further claim to fame – he appeared on the ITV series ‘Just Amazing!’ – a programme where former motorcycle racer Barry Sheene interviewed people who had achieved feats of daring and survival.

Alkemade died in June 1987, long after his number had been called.

Here is a film of Nicholas recalling his adventure. (Note: it has a French voice over so it’s not possible to hear his account properly.)

Here are a couple of articles – from the RAF Museum and the Leicester Mercury – which document Nicholas’ war experiences in more detail.

by Julie Harper

With thanks to his granddaughter Charlotte Cooper for permission to use this image.

The Old Rectory and the bonfire of books

6 July 2020

The following story is from Loughborough resident David Taylor, a life-long congregation member of All Saints’ Parish Church.

‘It must have been about 1956 that the following events occurred.’

‘Chas and I had been good friends at All Saints and also at school for some time, so it was not unusual to find us on a Saturday morning hanging about together and getting into the things normally expected of young teenage boys.’

‘On finding us at a loose end on one particular Saturday morning, the church verger (Chas’s father) called us into the garden and said something like ‘’if you have nothing much else to do then I have got a little job for you both that will help me a lot.’’’

‘We asked in a guarded way what the nature of the job might be (never bite off more than you can chew.)’

‘There is quite a bit of old rubbish in the rectory garden plus a huge woodworm-infested book case and a pile of old books left by Canon Lyon. I need to have them all burned by the end of today. Can I rely on you both to do it this afternoon?’’’

‘Well, no further encouragement was needed! It was home for lunch, a change of clothes and back to the rectory garden armed with a small amount of paraffin and a box of matches.’

‘The bookcase went first, followed by the general rubbish and finally we started on the books.’

‘They were as I remember quite a varied collection. Some were old and relating back to his early days in the ministry, others were signed and dated offerings from friends and relations, parishioners and fellow scholars. Most just smelt of damp and closed-up rooms.’

‘The burning continued until I picked up a beautiful red leather-bound book about A4 size with gloss paper pages and colour illustrations of all the cathedrals in the UK. Each illustration was protected by a single fly sheet of tissue paper, and the whole item just spoke of quality.’

‘I told Chas that we could not just burn an item like this and he said ‘’do as you like with it, I won’t tell my dad.’’’

‘The book went into the saddle bag of my bicycle, and thence back home.’

‘My parents seemed to be unexpectedly pleased with my rescue attempt asking (as might be expected) WHAT are you going to do with it?’

‘Now, Christmas was not very far away and presents for relatives was always a problem , even for my much loved aunt Kath and uncle Fred.’

‘An inspired moment: “I think … I think I will give it to Kath and Fred for Christmas,’’ I replied.’

‘In the end it turned out that they were delighted with it. Fred appreciated church buildings and loved books, but I did have to avoid an explanation of how the said item was obtained.’

The former rectory to Loughborough’s All Saints Parish Church is now a Museum run by volunteers from Loughborough Archaeological and Historical Society. You can find out about the history of the Old Rectory here.

To church on Sunday in times past

5 July 2020

In his 1979 publication ‘The Story of Loughborough 1888-1914,’ W Arthur Deakin, son of Echo founder Joseph Deakin whom he followed as director of the company, shared the childhood church-going memories of Mr Norman Bailey, a self-styled ‘Edwardian of Loughborough Congregational Church’ and himself the son of a local dignitary – Thomas W. Bailey, a former Mayor of Loughborough.

In the chapter, Norman recalls ‘the parade of families to church, Father resplendent in a silk hat, Mother’s hat a flower show; boys as near a replica of Little Lord Fontleroy as funds would allow, their outfits handed down from one generation to another; little girls a model of primness.’

The family sat in the pew ‘that grandpa and grandma once used,’ marked out by a card with their name on it, sitting ‘crushed together at one end’ to keep the children from fidgeting. As the service began, their mother passed along a single boiled sweet for each of the three Bailey children and their father unlocked a small cupboard and handed out the necessary books. ‘We knew what to do, and when,’ Mr Bailey says.

‘As the minister was arranging his notes, a low door in the panelling would open and out would come the organ blower.’ Before motorised bellows were invented, someone needed to peddle the bellows to generate the wind needed by the organ. Norman Bailey would later take this role at the Congregational Church, ‘keeping the lead on the string below the mark on the organ casing while the organist performed, hoping that he would not indulge in too much fortissimo which organ blowers know called for extra effort in pumping and more wind in the bellows. Thus, ‘There is a Green Hill Far Away’ was much preferred to ‘Onward Christian Soldiers.’’

Former congregation member Colin Price recalls ‘the service was usually five hymns, with one Old Testament and one New Testament reading, prayers of praise, confession, thanksgiving and intercession, sermon and blessing – normal for a Nonconformist chapel.’

The Bailey family sat opposite the church treasurer, Mr Rowland Hibbins, an ‘old man’ with a white beard reaching to his waist whose ‘opinions on all church matters were sacrosanct, even to the service finishing promptly at noon.’ As Mr Hibbin’s Sunday dinner was at twelve-thirty and he had a mile-long walk to reach it, he insisted the sermon finish at eleven-fifty and would ‘snap shut his large hunter watch for all to hear,’ whether the minister had finished speaking or not.

There was an evening service at the Congregational Church, which Mr Bailey described as ‘a little more adult’ and ‘usually packed with a congregation of around 450.’ During it, the minister ‘often preached for 40 minutes. Dads in their Sunday best blinked, faltered and then sat up straight again. Tired mums, their arms folded under their capes, mused quietly as the dimmed gaslight reflected on the sequins of their bonnets.’

The chapter concludes with a funny story from one of those evening services:

‘One winter’s evening the service was drawing to its close, the caretaker standing in the porch, waiting to lock up. He was talking to a young man waiting for his lady-love, a member of the choir. From time to time he put his ear to a crack in the door to assess progress. But the minister preached on.’

‘Is ‘e done?’ asks the young man.

‘No, ‘e’s not done,’ said the caretaker.

‘I’ll have a walk round,’ says the young man.

‘Yes, you do that,’ came the reply.

Back a little later, ‘is ‘e done?’

The caretaker again went to the crack in the door. After a pause, ‘aye, ‘e’s done,’ says he at length, ‘but ‘e’s not finished.’

From ‘The Story of Loughborough 1888-1914,’ (pub. Echo Press Ltd, 1979) by W Arthur Deakin.

Additional comments from members of the Remember Loughborough Facebook Group (June 2020).

Find out about Loughborough Congregational Church – now the United Reformed Church – here.

Read about church organs here.

Watch a film of the largest church organ in the world here.