On this day in Loughborough … 1872

26 September 2020

26th September 1872

It was very cold in Loughborough, with falls of snow, rain and hail, accompanied with thunder and lightning. At Shepshed, the ground was covered in snow. On 22nd September the temperature fell below freezing.

Snippets from the Loughborough Advertiser, Loughborough Herald and Loughborough Monitor.

Collated by Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers

Source: Matthew’s Local Newspaper Extracts Vol. 1

Queen of My Heart (a Soldier’s Verse Letter)

25 September 2020

Letter writing was the main form of communication between soldiers and their loved ones in World War One, boosting morale and filling up long hours spent in the trenches waiting for the next conflict to begin. It’s not surprising to learn, then, that the British Army Postal Service delivered around 2 billion letters and postcards during the war.

Below is an example of a Verse Letter, pre-printed with song titles popular at the time, for soldiers to send to their sweethearts. There were many, many versions of these ready-made letters, each with different verses.

This particularly letter was on show in the ‘WW1 – Home and Away’ exhibition staged by Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers in 2014.

A Message From Camp

‘My Heart is With You, Tonight’ love,

as ‘In The Shadows’ your dear face I see,

And, ‘I Wonder if The Girl I’m Thinking Of’

will ‘Sometimes’ think of me.

‘How Can I Bear to Leave Thee’ dear

for ‘The Sunshine of Your Smile’

brings to me ‘A Little Bit of Heaven’

‘Sweet Maid of Britain’s Isle’.

‘I Wonder if You Miss Me Sometimes’

‘My Wonderful Rose of Love’

‘Absence makes my Heart Grow Fonder’

‘Because’ I’m ‘True as The Stars Above’.

‘Oh Dry Those Tears’ ‘My Dearest One’

for ‘On Leave’ I’ll be ‘Home Again’,

cheer up, ‘Mavourneen’ and do not worry

‘Though Parting’s Such Sweet Pain’.

‘Say Au Revoir, But Not Goodbye’

for your ‘Laddie in Khaki’ is true,

‘Keep The Home Fires Burning’ bright,

‘Until’ I come back to ‘You, Just You’.

Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers

Read ‘Letters to Loved Ones‘ by the Imperial War Museum.

Email us if you have WW1 postcards or letters in your collection which you’d like to share here.

St Paul’s Church, Woodhouse Eaves, Leics

20 September 2020

Standing on high ground to the south of Woodhouse Eaves is the imposing church of St Pauls.

This church is much altered from the simple chapel, as originally built, to the design of the London architect William Railton.

Railton was no stranger to Leicestershire having designed Grace Dieu Manor and three lodges for the Garendon Estate. The largest cluster of his life’s work can now be found in the county including Beaumanor Hall, arguably his masterpiece.

His most famous work is, however, his monument to the national hero, Horatio Nelson, known to most as Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square, London.

At Woodhouse Eaves, Railton was faced with the difficult task of placing his church on a shelf of natural granite between woodland and the village. The church is slightly off the E to W alignment and this might be a clue to the difficulty of the topography of the site and may have followed the foundations of a house that stood on the site. The land was provided by a Miss Watkinson.

The church was built of the local natural granite and the roof was covered in Swithland Slate

A small cavern cut in the natural granite, Stone Hole Quarry, is still extant slightly to the west of the church, evidence of one of the quarries used to supply the building material.

The drawings of the original design survive and show the nave on the same footprint as the present one, a smaller tower and a mere token of a chancel with a rather insignificant chancel arch.

An interesting feature was a gallery or organ loft at the west end of the church.

St Paul’s was one of two almost identical churches built at the same time to the same design. The other church was St Peter’s at Copt Oak. Both were to receive Whitechapel bells to be later replaced and increased in number by local ones from John Taylor’s of Loughborough.

At this time William Railton briefly had Ewan Christian as his assistant and ironically it was Christian who was responsible for most of the later renovations and alterations we see on the present-day church.

The church was conceived by William Perry Herrick of Beaumanor Hall in Woodhouse and it is therefore no coincidence that William Railton was chosen as the architect following his designs for Beaumanor.

Although Beaumanor Hall is situated in Woodhouse (known locally as Old Woodhouse), most of its estate extended into Woodhouse Eaves and its environs were where many of the estate workers lived. The smaller but much older church of St Mary-in-the-Elms in Woodhouse had been found to be unable to service the outlying congregation.

The builder selected for this new church was William Kirk of Leicester. The work was completed in 1837, with consecration by the Bishop of Lincoln on Tuesday September 5th following the consecration of the twin church at Copt Oak the previous Sunday.

Such was the growth in church-building at the time that Emmanuel Church in Loughborough was also consecrated by the bishop on the Monday between the two Railton “twins.”

St. Paul’s church cost £1,000 when built and like its sister at Copt Oak, relied on voluntary contributions.

The original church seated 412 with the majority seated in the nave, although there would also have been some in the gallery (organ loft) which would have been accessible by the tower. The original building would have had plain glass in its lancet-style windows.

In 1838, the year following the building of St Paul’s church, William Railton was appointed Architect to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners – a post he held until 1848.

In 1871 the chancel was rebuilt under the architectural control of Ewan Christian, Railton’s former assistant. This work was the gift of and carried out by Charles Ashton, who dedicated the east window to his wife Ada May. This was to be the first stained glass window in the church.

This new chancel was later to suffer movement and required the successful application for a National Lottery grant in 2017 to action urgent repairs.

In 1880 major work was carried out, including the replacement of the roof and strengthening of the foundations.

Two transepts were also added and the Railton gallery removed. Ewan Christian was again the architect, with building carried out by Henry Black of Barrow-on-Soar. The south transept was the gift of Sir William Salt, who with his wife, is buried in the churchyard next to this part of the church.

It is interesting to note that during these post-Railton renovations, Ewan Christian was now Architect to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, a post he held from 1851-1895.

Further alterations were carried out in 1894, again to the plans of Ewan Christian. An organ chamber was added and the windows in the south transept enlarged. The builder of the work was Oliver Wesley of Woodhouse Eaves.

In 1904 six new bells were hung in the tower to mark the life of Queen Victoria and were cast by John Taylor Bellfounders of Loughborough. This installation required the strengthening of the tower and the rebuilding of the upper part. This resulted in increasing the height of the tower, which was also adorned with the installation of a clock by Messrs. J. Smith and Sons of Derby, the gift of the Vicar of the parish, the Revd. Arnold James. Of Railton’s Leicestershire churches only Groby retains its original Whitechapel bells.

Subsequent work saw the remaining plain windows being replaced by stained glass examples.

It is almost certain that the much-altered old vicarage that stands to the east of the church is also to the design of William Railton. The reason for this belief lies in the Tudor revival style and its date of build being complimentary to that of the church. Railton had used this style locally at Grace Dieu and was to use it again with his Garendon lodges.

Following the building of St. Peter’s at Copt Oak and St. Paul’s at Woodhouse Eaves, Railton also designed two other Leicestershire churches. These were St Phillip and St James at Groby (c.1840) and All Saints Thorpe Acre with Dishley (1845). He was also responsible for designs of other local buildings and renovated others. These included the original Mount St Bernard monastery, and renovations of Quorn Court, St Botolph’s Church, Shepshed, St Mary’s in-the-Elms, Woodhouse and Launde Abbey.

Ewan Christian was the architect for St. Marks Church at Leicester and the restoration of others.

Tony Jarram

Honorary Member of Loughborough Library Local Studies Group

Bibliography

www.stpaulsheritage.org St Paul’s Heritage Project Woodhouse Eaves.

Hodge Mary, St Paul’s Church Woodhouse Eaves, A Guide to the Church (2006)

Jarram Tony, Dyer Lynne, William Railton Architect 1800-2006, Illustrated talk (2018 revised 2019 and 2020)

Jarram Tony, Dyer Lynne, St Paul’s Heritage Project Woodhouse Eaves Volunteers, William Railton, display panel and research (2018)

Jarram Tony, Dyer Lynne, St Paul’s Heritage Project Woodhouse Eaves Volunteers, Ewan Christian, display panel and research (2018)

Special Thanks

To Sue Young and the St. Paul’s Church Woodhouse Eaves Volunteers Group for permissions to use publications and historical data.

Lynne Dyer who shared the research work for the St Paul’s Volunteers Group

Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers for hosting a William Railton Exhibition

The Mayflower and Loughborough – is there a connection?

18 September 2020

The year 2020 marks the 400th anniversary of the voyage of the ship Mayflower from Plymouth to America.

A significant number of the Pilgrims who boarded the Mayflower came from the religious congregations of Separatist Puritans. Fleeing from religious persecution in England, they had settled in Leiden in liberal 17th century Holland. They held Puritan Calvinist religious beliefs but unlike most other Puritans, they believed that their congregations needed to break away entirely from the English state church.

While Mayflower was berthed on the River Thames, 65 passengers went on board in mid-July 1620. The ship then proceeded via the English Channel to the south coast, anchoring off Southampton Water. On 22nd July they were joined by the ship Speedwell bringing Separatist Puritans from Holland.

They set sail in convoy on 5th August 1620, but Speedwell began to leak and both ships sailed into Dartmouth for repairs to the Speedwell. A week later they set sail again and 300 miles from Land’s End, once again Speedwell took on water. They returned to Plymouth. By this time it was early September and Speedwell was declared unfit to sail. So it was that some of the Speedwell passengers joined the Mayflower and some returned to Holland.

With a crew of up to 30 officers and men, Mayflower alone set sail from Plymouth on 6th September 1620*, carrying 102 passengers, of whom about half were Separatists. The ship also carried extensive stores for the voyage and for their future lives – tools, weapons and live animals such as dogs, sheep, goats and poultry. Two small boats were among the cargo.

During the voyage many suffered from seasickness and the ship was hampered and damaged by huge waves, requiring vital repairs to the ship’s main beam. Navigation was by compass. They arrived in America on 9th November 1620, having taken 66 days to cross the Atlantic.

Their aim was to reach the colony of Virginia but strong seas forced them on to Cape Cod, north of their intended destination, and there they anchored on 11th November. While still on board ship, the settlers drew up and signed a document called the ‘Mayflower Compact’ in an attempt to establish legal standing – they pledged to cooperate for the good of the colony.

On 27th November, 34 people set sail in one of the small open boats in an effort to search for a settlement site. Bad weather forced them to spend a night ashore but they were badly equipped to face the freezing temperatures. During that winter the passengers remained on board the Mayflower but disease took its toll. Only 53 pilgrims survived and half the crew died.

In the following spring, huts were built ashore and on 21st March 1621 the Pilgrims disembarked. Six iron cannons were mounted above the settlement for fear of native attack and the Plymouth colony was established. It was to be the second successful English settlement in America, following as it did Jamestown, Virginia, founded in 1607.

The Mayflower connection with Loughborough has five degrees of separation. A Pilgrim on the Mayflower voyage was one William Brewster, thought to be originally from Nottingham. Brewster’s famous descendant was his ninth great grandson, the crooner Bing Crosby who famously sang The Bells of St. Mary’s. The St. Mary’s church in question happens to be St. Mary’s church in Southampton, the bells of which were manufactured here in Loughborough by Taylor’s Bell Foundry.

Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers

References:

Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pilgrims_(Plymouth_Colony)

Mayflower 400 https://www.mayflower400uk.org/

*In the old style calendar – the date would’ve been 16th September in the modern calendar.

Find out more about why the Pilgrims decided to start a new life on the other side of the world here.

(Photo: Murgatroyd CC bySA4.0 Wiki Commons)

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

History at Home: winter talks by local history group

15 September 2020

The Friends of Charnwood Museum are staging monthly talks on a variety of historical subjects, each with a local flavour.

Talks take place on Wednesdays at 7.30 pm and will be held virtually via Zoom. They are Free to view at present.

Call Charnwood Museum on 01509 233754 or email museum@charnwood.gov.uk for the secure link to each talk.

(Please note that due to restricted opening hours, you must contact the Museum a few days prior to each event.)

The talks are as follows:

The History of Women in the Police Force… a Fair Cop

Wednesday September 16, 7:30pm

Host: Helen Reid

An ancestor of Helen’s husband was the first policewoman in London, so along with this personal connection and an insight into her working life, Helen will take the Friends on a fascinating journey!

Digging the dirt… Archaeology

Wednesday October 21, 7:30pm

Host: Martin Tingle

Join the Friends of Charnwood Museum as they look at Archaeology through the eyes of an archaeologist in five stages. It is a humorous, down to earth talk, from the early archaeologists to modern day with regards to Martin’s own career.

Witches in Leicestershire

Wednesday November 18, 7:30pm

Host: Sandy Leong

A witchcraft craze swept through England starting in the mid 1500’s and Leicestershire was no exception in having witches living in their communities. There are records of witches in Walton on the Wolds, Ashby de la Zouch & other places. Trials and executions were held in Husband Bosworth and a high profile case surrounded Belvoir Castle.

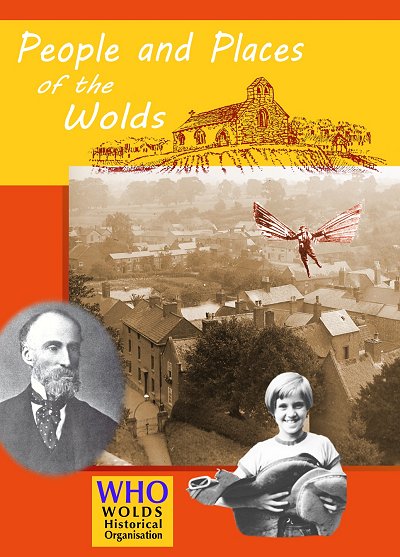

New book published on People and Places of the Wolds

14 September 2020

This month sees the publication of a new local history book by the Wolds Historical Organisation, an active group of enthusiasts who research and share the history of the villages of Burton on the Wolds, Cotes, Hoton, Prestwold, Walton on the Wolds and Wymeswold.

Produced by a group of writers, this collection of essays and biographies starts with pagan Anglo-Saxon settlers and continues to within living memory – at least living memory for the contributors, if not everyone living in the Wolds now.

A great many of the contributions are about the people who were born or lived in this part of north Leicestershire. Herein are the ‘great and the good’ and all types in between. They include:

a locally-famous schoolmaster-cum-antiquarian;

two men who collected plants and climbed mountains;

a soldier involved in the Charge of the Light Brigade;

a man transported to Australia;

the ‘gentry’ who built Burton Hall;

all the owners and occupiers of one of the manor farms;

a Second World War airman who miraculously survived;

a once-famous speedway rider; and

a girl with a passion for riding horses.

Published in September 2020, the 113-page paperback contains 19 colour photos, 84 b&w photos and 2 maps and costs £11.95 (£9.95 + £2.00 p&p).

Email who@indigogroup.co.uk to order.

To build or not to build … Blackbrook Reservoir

13 September 2020

Nanpantan Reservoir was completed in 1870, to much celebration.

As well as providing filtered water to Loughborough’s inhabitants, one bonus of the new reservoir was that for the most part, it eased the regular flooding of the town and made a huge difference to areas such as the Rushes and the streets around the Tatmarsh, which had frequently been under water when it rained.

A negative was that almost from its beginning, the reservoir was woefully inadequate to supply the needs of the growing town.

In his report in 1849, General Health Board inspector William Lee had recommended an extension to the reservoir on the Blackbrook out near Thringstone, built in 1796 to feed the Charnwood Forest Canal that became redundant with the arrival of the Charnwood Forest Railway. In 1866, Henry Fearon and friends’ limited liability company had again looked at this site, judging that a reservoir there would hold 75 million gallons of water. The Local Board had chosen Nanpantan instead, using the Wood Brook as the source of water.

In 1879, aware of the need for an additional supply, the Local Board offered to buy the rights to the Blackbrook from local landowners the de Lisles. A provisional deal was agreed and then mothballed until 1882, at which point Mr de Lisle asked for £7,000. Still the Local Board did nothing.

In 1884, however, an extended lack of rainfall forced their hands, causing a drought that impacted on the whole of the country and posed a very real threat to lives and livelihoods. By 20th October the Nanpantan reservoir was empty but for a trickling stream of water down the centre.

A temporary supply was quickly sorted, with Local Board surveyor George Hodson creating filter beds in Burleigh Brook and extending a water main along Derby Road near to the train station (now the site of a Lidl supermarket.) Water from these measures was pumped into town pipes and restrictions placed on its use until a heavy winter snowfall and rapid thaw began to re-fill the reservoir.

This emergency prompted the Local Board to return to the idea of a reservoir at Blackbrook and in early 1885, they approached Mr de Lisle and his agent to discuss it. By now, the price for the rights and easements had risen to £10,000.

The year moved on but the plan for the reservoir didn’t.

The story goes that one afternoon, a visitor to the town casually mentioned that engineers working for Leicester Corporation were up at Blackbrook, taking levels and testing its watershed.* After months of inaction the Local Board were suddenly electrified. The Board’s Chairman dashed over to de Lisle’s land agent at Ashby along with its clerk and solicitor.

Once there, they agreed to buy the rights and easements of the Blackbrook for £15,200. Mere hours later, members of Leicester Town Council arrived with an offer of £27,500.

Leicester officials later presented a Bill before Parliament to gain possession of Blackbrook’s water supply. In the words of The Loughborough Echo’s Joseph Deakin writing in 1927:

‘How Loughborough contested this measure, how the Local Board fought and won, how the representatives returning victorious from the law courts in London were met at the railway station by a brass band and a host of gratified residents – these facts were subject for commendation for some time.’+

Parliament approved Loughborough’s request to buy a hundred acres of land and build a reservoir at Blackbrook in June 1897. George Hodson – the engineer who so deftly saved the town from drought in 1854 – was the man responsible for designing the gravity dam. Construction began in 1900 and was completed in 1906.

‘Intakes were made at Blackbrook, a pipe was laid along the bed of the old canal to Nanpantan, and thus was Loughborough freed for years from the menace of a water famine.’+

Sadly, Archdeacon Fearon didn’t live to see the completion of the Blackbrook project first raised when he was newly-arrived in Loughborough and supported by his own limited company in 1870. He’d passed away in June 1885, bringing to a close a thirty-seven-year career as the town’s principle clergyman.

It would be interesting to know what Fearon’s thoughts were on the drought of 1884; whether, at 82, he’d been active and able enough to walk the streets of the town and see the hardships of its inhabitants as they coped day-to-day with a rationed water supply; and if he had, whether he’d passed the drinking fountain he’d so jubilantly gifted to the town and wished the Local Board of 1870 had chosen to use the better brook right from the start.

Alison Mott

*A watershed is the area of land that drains into a stream, river, lake or pond. The watershed for Blackbrook covers over three thousand acres.

+’Loughborough in the XIXth Century’ by Joseph Deakin. Pub Echo Press Limited, 1927.

Find further information on the Blackbrook Reservoir here.

The area around Blackbrook Reservoir is now a nature reserve and part of the National Forest that has grown up around North West Leicestershire.

There are several walking routes around the reservoir. Here’s one from the GPS Cycle and Walking Routes website and a circular 6-mile walk created by the Ramblers from Mount St Bernard to Blackbrook.

And here’s another walk from Mount St Bernard to both Nanpantan and Blackbrook reservoirs.

Read the previous post in this topic thread here.

How Henry Fearon brought water to Loughborough

4 September 2020

Loughborough’s Local Health Board may have given in to pressure and sorted out the sewage problem in the town, but that was all they were prepared to action from William Lee’s recommendations to the General Board of Health in 1849. Despite regular water shortages in dry spells, inhabitants had to make do with obtaining water from wells just as they had in times past.

In 1866 Archdeacon Henry Fearon decided once again to take action. This time, rather than shaming the Board by confronting them in the press, he took practical steps to remedy the situation himself. He and a group of local businessmen dipped into their pockets and clubbed together to form a limited liability company intent on bringing clean water to the town.

The company drew up a scheme for a reservoir between Shepshed and Whitwick which would hold 75 million gallons of water, sourced from the Black Brook. Then they prepared a bill to seek permission from Parliament to action the scheme. They planned to float the company on the stock market, raising £15,000 in share capital to cover the cost of construction. They let the Local Board know of their plan in November that year.

The Local Board immediately rejected the idea, stating they were planning to construct a water scheme themselves. They refused to hold a public meeting to share the details of this, however, so Fearon’s company went ahead and held their own, sharing their plans with townsfolk on 8th January 1867.

The meeting was a heated one, with strong opposition to the piped water scheme even though it wouldn’t affect the rates as only those prepared to pay for the water would have it connected to their homes. Finally, Archdeacon Fearon stood up to address the meeting.

An intelligent and articulate speaker, he pointed out the benefits of a good water supply for the town – the 200 houses in Woodgate whose inhabitants had to go ‘a considerable distance’ to get pure water but could instead have it piped directly to their bedrooms; the public wash-house that could be built for locals to bathe in and do their laundry; the poultry market that could take place once there was water on tap to wash it clean afterwards.

Fearon mentioned the expense that would result from a dispute before a Parliamentary Select Committee and raised concerns that with committee elections due in March, the Board’s own plan for a waterworks might once again be postponed.

And he told the crowd that though he’d helped set up the company, he didn’t care a ‘snap of his finger’ who provided a water supply and wouldn’t oppose the Board’s plan to do so ‘if they were sincere.’

The debate would continue for many months. On 11th November 1867, the Local Board voted to apply to Parliament for a Waterworks Act but after a public outcry, were persuaded not to proceed. Five Board members resigned over the matter but were soon re-elected and their own scheme finally went through. The company set up by Henry Fearon and his friends was given £150 in compensation for the monies they’d already laid out.

The Local Board ‘got out and dusted down’ old plans for a reservoir and filter beds at Nanpantan. Built on an 8¾ acre-site and holding 29 million gallons of water taken from the Wood Brook, the waterworks cost £23,500 and were opened in 1870.

Clean water had finally come to the town and Henry Fearon commemorated this momentous event by installing a drinking fountain in the Market Place, drawing the first draught of water from it on 31st August.

Unfortunately, Loughborough had grown so much since William Lee had assessed it in 1849 that the supply from Nanpantan reservoir was inadequate almost immediately it was opened. Some fifteen years later after a number of droughts in the town, the Local Board of Health had no choice but to buy land for a second waterworks to meet demand.

In a final act of irony, this new reservoir would be built on the Black Brook, on the exact site Fearon and Company had suggested back in 1866.

Alison Mott

Read the previous post in this topic here.

Read the next post in this topic here.

Loughborough’s Sewage System Sorted

2 September 2020

In June 1852 – after public pressure fuelled by the publication of a letter from Rev. Henry Fearon and his colleague Rev. J Robert Bunce – the Local Board of Health officially agreed to sort out a decent drainage system for Loughborough.

They appointed an engineer from Nottingham – a Mr Hawkesley – to survey the issues and come up with a scheme for putting them right. In July 1852 – three years after William Lee had made his recommendations – Hawkesley delivered his report.

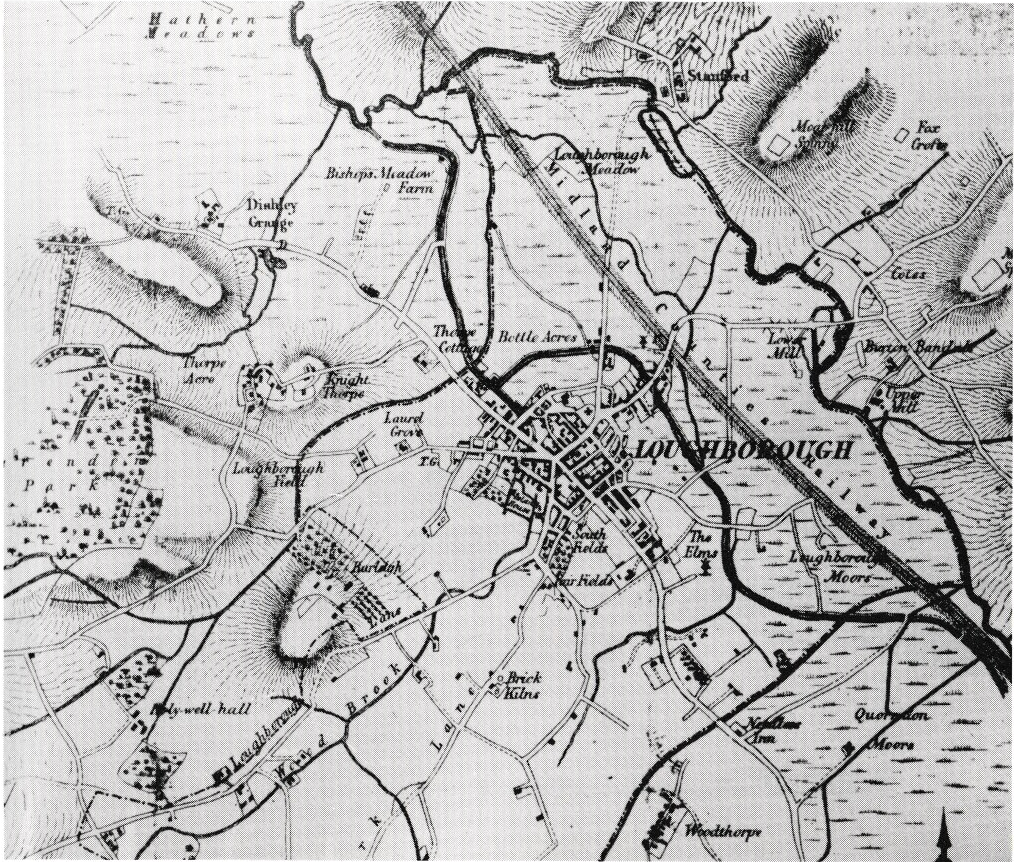

His plan was to install three main sewers to lead waste away to brooks on the edges of town and from there, into the River Soar. The drains would fall into the Armitage Brook near the old Midland Railway Station and the Wood Brook shortly below its junction with Burleigh Brook. The third outlet would be a brick culvert out at Bottle Acre.

It would be another two years before the Local Board completed Hawkesley’s drainage system, borrowing £8,000 to cover the cost. The drains made a huge difference to the cleanliness of the town.

They also reduced the water in the public pumps, causing water shortages in very dry weather and bringing criticism down on the Local Health Board for not having sorted out a new water supply first.

Even so, it would be many more years before the water problem was dealt with, and it would happen in a very dramatic way.

Alison Mott

Note: The drainage works were updated in 1895, when intercepting sewers were laid from the three outfalls to take the waste to the newly built sewage plant rather than to the Soar. In modern times, the sewage is taken directly to the sewage plant in one single pipe.

Read the previous post in this topic thread here.

Read the next post in the topic here.

Fearon and Bunch take on the Local Board of Health

1 September 2020

In 1849, General Board of Health inspector William Lee ended his inquiry in Loughborough and left, his report available for anyone who wished to buy a copy from the local printer tasked with distributing it.

In it, his recommendations for improving the health of local inhabitants were listed, beginning with the need for a filtered water system, piped to every house in town, followed by drainage and underground sewage systems to carry waste away from the populated areas. Next, he suggested the town’s roads be paved and regularly cleaned, anticipating that all these actions would stop the Wood Brook being polluted on its journey from Ward’s End to the Canal Basin.

In late 1849 Loughborough’s Local Board of Health was set up to act on Lee’s recommendations, quickly taking over the duties of the Board of Surveyors. Aware of the need to avoid increasing the rates, they only adopted some of the suggestions. They cleared drains and ditches, organised the repair of the town’s bridges, impounded stray cattle and in time, turned their attention to providing other amenities for townsfolk, approaching the local gas company in 1857 to commission them to supply street lighting.

But they did nothing immediate about providing a clean water supply, and without installing an underground sewage system, failed to deal with the waste matter of the town’s eleven thousand inhabitants.

And complaints from residents came in thick and fast –

‘overflowing drains,’

‘pigsties draining into wells of public drinking water,’

‘night soil deposited in the streets,’

‘80 houses in Wood Gate and Pinfold Gate without water,’

‘the ‘open’ Wood Brook with the sewage of 1175 inhabitants in 217 homes emptying into it, ‘breeding fever and disease’ from one end of town to the other.

In 1852, Henry Fearon stepped in to do something about it. As parish priest, he was the principal clergyman in the town and therefore an influential man locally. But he had no official power to exert pressure on the Local Board of Health.

Fearon didn’t let that stop him, though. Instead, he used the influence he did have to exert pressure of a different kind.

In May of 1852 a letter from Rev. Fearon and his colleague, Rev. Bunch of Loughborough’s Emmanuel Parish, was published in the ‘Leicester Journal.’ It was addressed to ‘the Chairman and Members of the Board of Health, Loughborough’, and ended with the statement that given the importance of its subject matter, the authors hoped the Board ‘will not think us disrespectful toward yourselves if we give publicity to this letter.’

The clergymen said they could ‘keep their peace no longer’ over the delay in providing the town with the much-needed sewage system, repeating the issues stated by Lee in his report and adding more of their own. Chief of these was the rise in the town’s mortality rate from 28 per thousand to over 30, exacerbated by outbreaks of smallpox.

Whilst the Rectors understood it was difficult persuading ratepayers to meet the cost of proper drainage, they pointed out that it would prove cheaper in the long run, reducing the ‘heavy charges for the sickness of the poor and their consequences.’ They also reminded the Board of their duty ‘to alleviate and prevent the sufferings of humanity.’

The letter was a clever piece of public shaming, leaving the Board unable to ignore the need for action. Though its chairman – hosiery manufacturer J. Cartwright – did his best to refute the Rectors’ claims, the Local Board of Health officially admitted on 7 June 1852 that a complete system of drainage was unavoidable and therefore ‘must eventually be carried out.’

Alison Mott

Read the previous post in this topic thread here.

Read the next post in this topic here.